I’m an American psychiatrist who, over the last 20 years, has, with my Center for Mind-Body Medicine (CMBM) colleagues, developed and implemented parallel programs of population-wide trauma healing in Gaza and Israel, as well as during and after wars in the Balkans, Africa, and Ukraine, and after climate-related disasters, mass shootings, and historical trauma in the United States and around the world.

Right now, in a time of unbearable crisis in the Middle East, when stories of Gazans’ ordinary humanity can be overshadowed by the grim facts of the conflict between Hamas and Israel, I want to tell you about Jamil Abdel Atti, PhD. He is the extraordinary Gaza psychologist who has, from the beginning, led CMBM’s program. He continues to lead our program now in the midst of mass death and destruction—and in the face of the world’s divided and often dehumanizing perspective on Gazans.

Seeing the Gazans

Since Hamas’s October 7th massacre of 1,200 Israelis and its kidnapping of 250 hostages, U.S. newspapers and news channels have offered thoughtful, sympathetic portraits of horribly harmed Israelis. Interviews with hollow-eyed Israeli hostages and urgent, grieving families have been accompanied by pictures of their loved ones and hobbies. In essence, they were and are real and decent people, with whom we can easily identify.

The coverage of Gazans has been different. For the most part, and perhaps understandably, we see them only in dramatic and painful outline: Palestinian surgeons amputating the limbs of screaming children without anesthetics or antibiotics, because none are available; videos of rows of kids with half their faces destroyed, their bodies wrapped in white bandages, and grown women and men weeping and howling at their death. There have been few in-depth interviews and almost no accounts of Gazans savoring and celebrating their lives as well as coping with their terrible losses.

Jamil works in the midst of all the violence and heartbreak, a real person whose great compassion and suffering are married to an equally great appreciation of the ordinariness and joy of life.

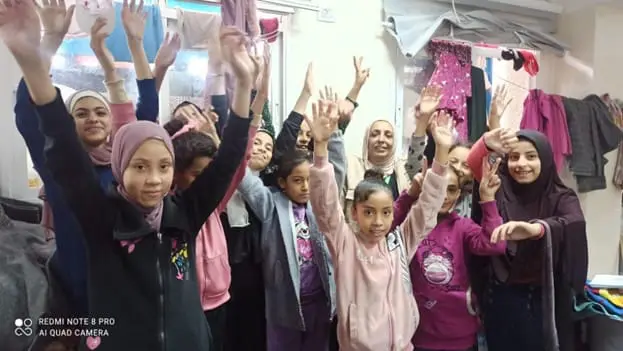

That’s Jamil in the tan vest on the left in the picture above. He and the CMBM project manager, Ramadan El Helou, PhD (the other adult in the tan vest) are pictured here with some of the surviving Palestinian children who’ve taken our self-care workshop for kids, and who, several weeks ago, were living crowded together on hard shelter floors in a bombed-out Rafah neighborhood.

Jamil and Ramadan have taught the kids slow, deep, “soft belly breathing” to quiet their persistent fight-or-flight reactions. Almost all have overwhelming anxiety and disturbed sleep.

They’ve encouraged the kids to draw the fearful feelings that fill their days and haunt their nights. And they’ve led them in active, expressive, “shaking and dancing” meditations, during which they yell encouragement to help melt trauma-frozen bodies, to relax the tension that locks the kids’ limbs and binds their chests.

After the workshop, the kids act like kids. They make goofy faces and laugh and smile for cameras. Jamil smiles too. And the smile is genuine, just like his loving heart, which I can tell you is in immense pain. Two of Jamil’s sisters, and an entire three-generation family of one of them, have been killed in these last months. He and his children and grandchildren have fled their homes in the north, which neighbors recently told them have been destroyed, and relocated several times in the midst of Israeli bombings, to Khan Younis and Rafah in the south and back to Khan Younis in the Middle Area.

When we first began working together in 2004, Jamil and I seemed an unlikely pair. He, a dutifully observant Muslim, who grew up poor in the Khan Younis refugee camp with a farmer father who’d been forced to leave Israel in what Palestinians call the Nakba (the 1948 Israeli expulsion). I, a non-observant American-Jewish psychiatrist, who grew up privileged in Manhattan and was also establishing a trauma healing program in Israel.

Because his family couldn’t afford to pay for medical school, Jamil went to nursing school in the West Bank. He had coordinated Save The Children’s school mental health program in Gaza and, by the time we spoke, was prepared to believe that self-care and mutual support might be just what traumatized Gazans needed. Even at our first meeting, I knew I was with someone with the humility to be open and curious about techniques that were unfamiliar and challenging to a traditional Islamic community, and the clinical and administrative chops essential to leading a program.

Funded by a U.S. Congressional “earmark” from then Iowa Senator Tom Harkin, Jamil and I trekked from the government offices of the Palestinian Authority to the heavily guarded gates of the UN Relief and Works Agency, and through the long corridors of Shifa hospital where we visited patients and physicians. We spoke with leaders of opposition parties and international and local NGOs. Jamil treated all of them, including leaders of factions that competed, often violently, for the allegiance of Gazans with the same quiet appreciation.

In a land where for most people, including some of our trainees, “mental health” had signified hopeless, ostracizable craziness, Jamil worked with me to adapt our model to fit the constraints of an Islamic society. He encouraged our trainees to bring mindfulness into their five-times-daily prayers, set up screens so women and men could separately and comfortably stretch, shake, dance, breathe as fast as they could, and jump up and down and shout out their fears and frustrations.

When there was a question about whether a particular practice might be forbidden to Muslims, Jamil would sometimes give the floor to a diminutive psychiatrist from Rafah who was able to muster quotes from the Quran, assuring our trainees that the use of mental imagery or the creation of a genogram—even shaking and dancing—had precedents or analogies in Islam.

Jamil began to assemble the core of what would become our Gaza faculty. During the years prior to the current conflict, his team has trained more than 1,500 clinicians, educators, first responders, and the leaders of all the women’s centers in Gaza, in our model of self-care and group support. These trainees in turn had shared our work with 285,000 children and adults.

Outside of work, Jamil could be as painfully serious as the situation in Gaza, but there were times, especially when we gathered with the team to play cards in a tent at the beach or smoke water pipes with tobacco on the deck of a hotel, that he’d sit back and grin with pleasure and even tell a joke. Here’s one:

“A Jew, a Christian, and a Muslim from Gaza are in Hell, and all of them want to make phone calls home. The Jew says, ‘I have to go to the ATM because it’s going to cost a lot of money to call Tel Aviv.’ The Christian says, ‘My home is even further away in the United States. I’m going to have to withdraw even more money.’ The Gazan says, ‘I don’t have to go to the ATM. My home in Gaza is only a local call from here.’”

In a territory where just about everyone was suffering, Jamil was intent on bringing our program to those who were most in pain and least likely to receive adequate help. He brought me to ongoing groups for women with advanced breast cancer who were inadequately treated and too often spurned by husbands who no longer found them sexually appealing. Another time, we met with a group of female amputees who were largely confined to wheelchairs because their prostheses were poorly constructed. We shook and danced together, Jamil and I standing, the women in their wheelchairs (see photo below; Jamil is in the checkered shirt).

When Jamil broached the subject of ending the groups after the customary 12 sessions, the outcry was unanimous. “Before this, we hadn’t left our houses in two years. You have,” Jamil translated for me, as we silently agreed to continue the group, “given us a reason to live.”

And then, there were the meetings with kids: the kindergarteners with behavioral problems, nicknamed “the baddest little boys in Gaza,” but looking like angels as they did soft-belly breathing. Or the teenagers with Down Syndrome reclining comfortably as one of our faculty led them in guided imagery. “I dreamed,” said one beaming 13-year-old boy, “that I was with my father who was martyred in the last war. We were eating apples in Paradise.”

Several years before Hamas’s October 7th massacre, and Israel’s retaliation, an Israeli-American entrepreneur who’d been moved by a 2015 60 Minutes segment about our work with war-traumatized kids in Gaza and Israel, funded a pilot program for children in 15 Khan Younis schools, which Jamil led. Our benefactor hoped that our program might guide angry, despairing children on the path to peaceful productivity.

And it was proving to be the case. Grades and attendance improved, violence between students and from teachers who’d themselves been traumatized by previous wars and the occupation decreased significantly. We were working to bring this program to all 300,000 kids in Gaza’s public schools when, on October 7th, Hamas attacked Israel.

Violence Closes In

On October 8th, as Israel responded to Hamas’ attack, killing hundreds of Palestinians, Jamil texted. “This time,” he said, “is different.”

And, indeed, it has been.

Within a few days, Jamil could feel the blasts of bombs far larger than any dropped in five previous wars, and he could see buildings around him collapsing. When he ventured outside, the streets were clogged with rubble and bodies: “So many children and women and old people. Do they not understand that we are human?”

Jamil wanted to stay in his apartment, as he had during previous wars, but, eventually, to preserve his family’s lives, he followed Israel’s orders, abandoned his home, and drove, dodging bombs and avoiding dead bodies, to a cousin’s house in Khan Younis—where, despite an Israeli military guarantee of safety, more death and destruction awaited them.

Jamil encouraged his team to care for their families above all, but invited them to go with him, if they could, to teach self-care techniques in the minimally intact schools, mosques, hospitals, and shelters. He shared grim photos and videos of death and destruction with me and our CMBM faculty and staff, but also pictures of the team working beautifully and enthusiastically. I and other CMBM staff and faculty, anxious about our team’s safety, awoke every morning and rushed to look at Jamil’s texts.

And then, on October 20th, Jamil was silent.

Early the next morning, we had a tense, strangled communication: “My sister and her husband, their son, and their two grandchildren, have been martyred.” Soon, at the command of the Israeli military, Jamil had to move again, from Khan Younis, now the center of fighting, to Rafah, where he and 45 of his family members came together in a house no bigger than the living and dining areas of a modest American or Israeli home, all supported in a time of calamitous scarcity and inflation by Jamil’s salary.

During the day, when they weren’t leading workshops, Jamil, Ramadan, and the other Gaza faculty searched for food. “Today,” Jamil reported, “we only have onions and tomatoes in the market, and onions are $25 a kilo.” They make their way back from the market slowly, through masses of people crowded shoulder to shoulder, pausing to look at the bodies of children wrapped in white shrouds, lined up like logs on the road.

Even as deaths in Gaza continued to mount—estimated now at more than 36,000 with perhaps thousands more buried under the ruins of buildings—Jamil endured even more painful intimate losses. Another of his sisters was killed, as were our faculty members, Shaher Yaghi, his psychologist daughter, Sumaia, and 20 members of their family.

And still, Jamil and the team continued their work (see photo above of Jamil speaking to a man in Rafah whose home was crushed by Israeli bombing). As of this writing, they have, since the present conflict began, helped nearly 40,000 children and adults. These kids and adults who participate in workshops, crowding the floors of the schools that are used as shelters, often feel significantly better, at least temporarily, after an hour and a half, and are restored to the loose, smiling ordinariness that you could see in the picture at the beginning of this article.

Of the thousands of traumatized children and adults who Jamil and his team continue to help, nearly all begin their time with CMBM overwhelmed by grief, sleepless, agitated, plagued by panic attacks and rage, and often emotionally numb and clinging to or avoiding their family members. Surveys of the team’s work with the most vulnerable (how Jamil and the team collected the data is itself a miracle) of 400 of them who participated in a series of five sessions of self-care and mutual help, revealed that almost 90% of the teenagers and more than 60 percent of the children were free of their most disabling symptoms, and no longer qualified for a PTSD diagnosis.

Still, the death and destruction continue. “Jim, everyone is terrified,” Jamil writes me. “The Israelis invaded Rafah and told us to evacuate. But how? To where? We went to Khan Younis and then to Nuseirat, and this morning (June 8th), right next to where we slept, bombs fell that freed the four Israeli hostages but killed more than 200 of us. There is no safe place. People are starving and have no water, and the children who are alive are so thin and so many are getting sick.”

Not long ago, when I asked Jamil how he manages to live through all of this, maintain his kindness and compassion, and work so skillfully and gracefully, he told me, “It is Allah who makes it possible. You know, Jim, I am always praying, and saying, ‘Inshallah, if God wills it.’ That means it is up to me to accept whatever losses come, however painful. I may not understand why. But I understand it is the will of Allah, and I do accept it. And I do the CMBM work I believe Allah wants me to do.”

Many of us who have grown close to Jamil also find ourselves praying that Jamil will survive this terrible war, that ultimately peace will come, and that we will return to Gaza to help Jamil and his team rebuild shattered lives and heal the minds and hearts of his people.

James Gordon

James S. Gordon, MD, is a psychiatrist, the founder and CEO of The Center for Mind-Body Medicine, and the author of Transforming Trauma: The Path to Hope and Healing. He is a Clinical Professor of Psychiatry and Family Medicine at Georgetown Medical School and chaired the White House Commission on Complementary and Alternative Medicine Policy. His work with war-traumatized children in Gaza and Israel, both of which he has visited 20 times, has been featured on 60 Minutes in 2015, as well as in The New York Times and The Washington Post.