“Shhh!” we hear from the darkness, followed by the sounds of innocent giggling. “They’re gonna hear us.” Next, we see two 13-year-old boys playing in an underground hideout. But who’s the unspecified “they” that the boys think are coming for them? Other kids? Enemy soldiers? We, the audience, peering in on their private fun?

“On the count of three, you run to get away,” one says to the other. “One. Two. Three!” And then they’re off, happily racing through a field of flowers in the golden sun, laughing as they go. The image is one of pure life, pure joy. But how long can this playfulness last before the ominous “they” catches up with the boys and destroys their loving and generative connection?

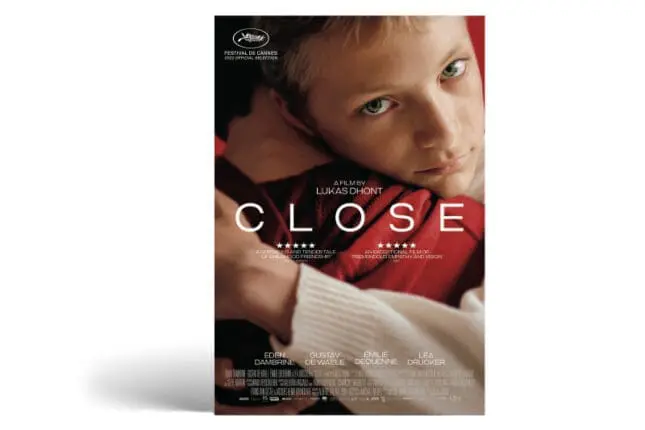

This is the opening scene of Belgian director Lukas Dhont’s astonishing, Oscar-nominated film Close. This movie is essential viewing for anyone, especially those of us who raise or work with children. Not only is it an exquisite cinematic experience with gorgeously nuanced performances from Eden Dambrine and Gustav de Waele, who play the two leads, Léo and Rémi—it’s a poignant reminder of the essential nature of human connection, specifically, the beautiful, empathic relationships that come naturally to young boys, but that our society tends to squash.

As developmental psychologist Niobe Way writes in Deep Secrets: Boys’ Friendships and the Crisis of Connection, which provided the inspiration for Close: “The story of development for boys . . . is a story of loss and disconnection from their peers.” Her research shows that as boys get older, they often want “the intimacy that they had when they were younger,” but fear actualizing this desire lest it be deemed “gay, girlish, and immature.”

Along these lines, as you witness Rémi and Léo playing and showing affection throughout the movie, you might find yourself wondering, “Are these boys gay?” The film never answers that question, nor does it suggest any particular sexuality for either boy. But the fact that we might ask this is Dhont’s point. Why, when two young people play, laugh, share a bed, and inspire tears in one another with their talents for storytelling and music, do we feel compelled to apply unnecessary labels to them?

The answer lies in Way’s research, which links our tendency to create emotional distance between boys to “a culture that idolizes ‘stupidity’ and stereotypic masculine behavior” and rejects empathy—derisively equating it with being gay, feminine, and childish. The implicit force of social regulation, as psychoanalyst Ken Corbett puts it, works to police boys like Léo and Rémi through all of us before we even realize we’re doing it.

And yet, even as a gay man who’s experienced a lifetime of social policing, I found myself wanting Rémi and Léo to avoid scrutiny by muting their unabashed mutual affection for one another as they enter high school following their summer of platonic love. It’s hard to admit this, as I’ve spent the better part of my life working to challenge such reactions, but the truth is that fear ushered me into a mode of protection, despite the sublime connection of these two boys.

Indeed, Rémi and Léo’s peers bombard them with questions—“Are you two together?”—but as distressing as it is to witness these interrogations, Dhont doesn’t allow the meddling teens to be the only perpetrators. As Rémi and Léo walk from class to class, leaning on one another at lunchtime like puppies, we, the audience, are forced to confront our own implicit biases about teenage boys interacting this way in public. As I watched, I felt myself gradually absorbing the judgment surrounding them and internalizing shame and primal fear on their behalf.

I held my breath the moment Rémi rests his head on Léo during a break between classes—unaware of jeering classmates—and the more socially vigilant Léo gently removes it from his shoulder. How the forces of social regulation continue to play out cinematically—ultimately tearing these boys from their nourishing attachment—is both devastating and entirely worth experiencing. After all, Dhont reminds us that the narrative he’s dramatizing onscreen unfolds on our watch between boys everywhere, every day.

But there’s hope and possibility glimmering through even the darkest, most heartbreaking moments of Close: notably, the way the boys’ parents are forced to confront their own grief and recognize their need for connection. Which brings me to the place that Close hits me hardest: as a parent. My husband and I express gratitude daily for the quantity and quality of unabashedly loving and affectionate relationships that our five-year-old son is able to have with other boys in the New York neighborhood where we live. It’s a beautiful sight to behold our son and a friend calling out to one another on the street like Rémi and Léo do, hugging, holding hands: all these demonstrations of affection seamlessly mixed in with their more socially expected and accepted male behaviors, like racing on scooters, pretending to be superheroes, and exchanging Hot Wheels.

At a recent dinner with our son’s best friend’s mom and dad, our boys waltzed up to the table where we were chatting and said, “We’re going to get married one day and have a baby girl.” No one cringed or communicated that anything was wrong or misguided about their vision. “That’s great,” my husband said. “What will you name the baby?” “Hazel,” my son’s friend said.

Sweet as this interaction was, I found myself immediately mourning it. Although we’ll support these children in marrying whomever they want to marry, or in choosing not to marry at all, I know all too well that sooner or later some form of social regulation will squelch their freedom of expression and the vibrant possibilities from which their momentary vision was born. What I fear will be lost is their ability to play, dream, and speak the myriad possibilities that are available to them out loud without being punished. As parents, we can’t stop this, but we can help them name and counter the implicit, nonverbal messages that will inevitably interfere with their ability to stay in relationship with one another through disruptions.

Recently, I put this idea to the test during a playdate. My son and his friend were disagreeing about something on TV (“It’s this,” “No, it’s that!”). The argument escalated until the boys seemed to be on the brink of blows. “You’ll lose your fire truck for the day if you hit him,” I warned my son. He took a moment to think before deciding that it was worth it to try and give his friend a good whack anyway. At this point, parents typically end a playdate, leaving the feelings of discomfort and disconnection unaddressed, especially between boys. But the dad of my son’s friend stayed engaged as I invited them to breathe and imagine different ways of hearing one another and making the points they wanted to make—an exercise I sometimes use with couples in my practice.

After a few minutes, my son’s friend leaned close and whispered in my son’s ear, “I understand.” He didn’t relinquish his perspective or submit to my son’s point of view: he simply let him know he understood it. His dad encouraged him to apologize for the conflict, but my son said, “No, no, it’s okay. I’m good. Let’s hug.” Watching this moment of mutual recognition unfold between the boys felt expansive, as if a light had opened in the sky. I wish the characters in Close could’ve had the same experience. More importantly, I wish their real-life counterparts, the boys and men who feel their bonds with one another being pulled apart relentlessly in our culture, could find it.

The next day, my son’s friend greeted him with a hug in front of their school. “Hey,” he said, “Remember yesterday when you thought the thing on TV was one thing and I thought it was another? Guess what: I still understand what you thought it was!” Then, as the other boy’s dad and I waved goodbye, they held hands and jauntily walked up the stairs to school, greeting their other friends with generosity and openness to possibility.

Mark O'Connell

Mark O’Connell, LCSW-R, MFA, is a psychotherapist and author in New York City. He teaches workshops based on his book The Performing Art of Therapy: Acting Insights and Techniques for Clinicians, and writes for Psychology Today and The Huffington Post, as well as clinical journals.