Enjoy the audio preview version of this article—perfect for listening on the go.

There’s a Motown saying that it takes one to stay in the dark alone, and it takes two to let the light shine through. In therapy, the spark that kindles a genuine sense of connection is our ability to bring our full presence into the therapeutic arena. Doing that often requires us to go beyond words to being present in our bodies and feeling our life force in the moment. In these times, when the fear of contagion overshadows our every action, one of our biggest challenges is to realize that physical isolation doesn’t automatically mean loneliness and emotional disconnection. Even as we monitor our physical proximity to others, we still have choices that enable us to distinguish between the pandemic outside and the panic-demic we can create within ourselves.

Courage is not about the absence of fear, but the capacity to act creatively in the presence of fear. Right now, some of the best ways to access our capacity for courage are doing things like listening to music, preparing meals together with the people we’re living with, moving and dancing with our inner rhythms, and finding ways to connect with others, even if the medium of that connection is virtual.

Knowledge is useless until it lives in the body. The emphasis of my life’s work as a therapist has been on learning about the processes of human healing by observing small changes in the body and developing observational skills to guide my therapeutic work. As Yogi Berra, a hero of mine, said, “you can observe a lot by watching.” That’s what I did when I was developing Somatic Experiencing. I learned to really see what was going on inside a person’s organism, to bring their attention to their interceptive landscapes—and that’s what we can do to help people now, even if it’s through video.

In Somatic Experiencing, we have a map for a person’s inner experience, called SIBAM, that can help clients focus their nonverbal awareness, especially in highly stressful times like these. S stands for sensation: bodily sensations, muscle tension, joint perception, visceral movements. I is for images, what comes from the outside into our inner experience. B is for behaviors. A is for affects, things like anger, fear, sadness, disgust, surprise—characteristic of all people everywhere in the world.

But A also refers to what sometimes are called contours of feelings, felt-sense feelings. You see somebody that you haven’t seen for a while and you’re filled with gladness. Gladness isn’t a categorical emotion: it’s a physiological experience, like when you walk out in the morning and see the dew on a blade of grass, the absolute beauty of it. That’s very important in our life. M stands for meanings. When a person has been traumatized, the meanings aren’t fluid anymore: they become concretized as fixed beliefs, like something bad is going to happen to me, or I’m unlovable.

The idea is to be able to help clients experience their inner landscape by observing the minute adjustments that their body is making, moment to moment. If you pay close enough attention, you can see in a person’s microbehaviors all kinds of autonomic shifts, what’s going on in the brain stem, the limbic system, the emotional brain. If someone is stuck in fear, their pupils may dilate, their heart rate may accelerate. You can observe all these things and help the person move through them.

This highlights Polyvagal Theory and the work of my dear friend Stephen Porges on the autonomic nervous system. We’re now in a situation where so many of us are experiencing or perceiving the potential of mortal threat by a pandemic. For many people, this situation will activate the dorsal system. The body wants to shut down, shut it out. For others, experiencing the world as a threat in this way will activate the fight-or-flight response of the sympathetic nervous system. This is how a traumatized person perceives the world, as danger and threat. And this is how many people are seeing the world now.

To find a sense of safety, we don’t want to get stuck in either dorsal or sympathetic regions of the autonomic nervous system: we want to shift into the ventral vagal system. A good way to do that now is to invite some movement and music into your lives, some drawing and dancing. You could dance with a partner if you’re in the same house, or with someone over video, or just dance by the window and get everybody in the neighborhood dancing. As quickly as possible, we want to move out of the state of perceiving only threat because it’s tremendously stressful, and it probably reduces our immunity to infection.

Of course, if there’s real imminent danger, then we’ll perceive that and be able to act accordingly to protect ourselves. Right now, that might just be washing our hands regularly and practicing physical distancing. But the ambient level of our nervous system, of our neuroception, should be safety, and we can do many things to help create safety in our environment. We have to do this so our ventral vagal system comes online.

A person stuck in dorsal vagal shutdown, hypoarousal, will generally move into sympathetic arousal, at least for a short period of time. So we move through the activation back to relaxed alertness. That’s the therapeutic key, move into ventral vagal safety, which can be characterized by our earliest experiences of being held, being comforted through touch, or even a facial expression.

Right now, people all over the world are reflecting and connecting in new ways. They’re waking up to the choices we make as to how to live today. So breathe. Listen behind the factory noise of your panic. The birds are singing again. Spring is coming. Open the windows of your soul, and though you may not be able to touch someone across the empty square, sing.

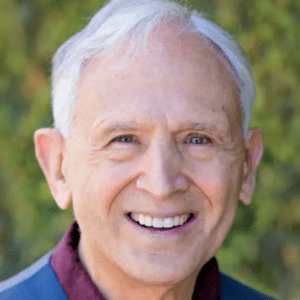

Photo by Sabel Blanco

Peter Levine

Dr. Peter Levine holds doctorates in both medical biophysics and psychology. He is the developer of Somatic Experiencing® (SE), a naturalistic body-awareness approach to healing trauma, which he teaches all over the globe. Dr. Levine is also the founder of the Foundation for Human Enrichment and was a stress consultant for NASA during the development of the space shuttle. An accomplished author, Dr. Levine penned Healing Trauma, Sexual Healing and the bestselling book, Waking the Tiger. He also co-authored with Maggie Kline Trauma Through a Child’s Eyes and Trauma-Proofing Your Kids. His latest book, In an Unspoken Voice: How the Body Releases Trauma and Restores Goodness, is a testament to his lifelong investigation into the connection between evolutionary biology, neuroscience, animal behavior, and more than 40 years of clinical experience in the healing of trauma.