Enjoy the audio preview version of this article—perfect for listening on the go.

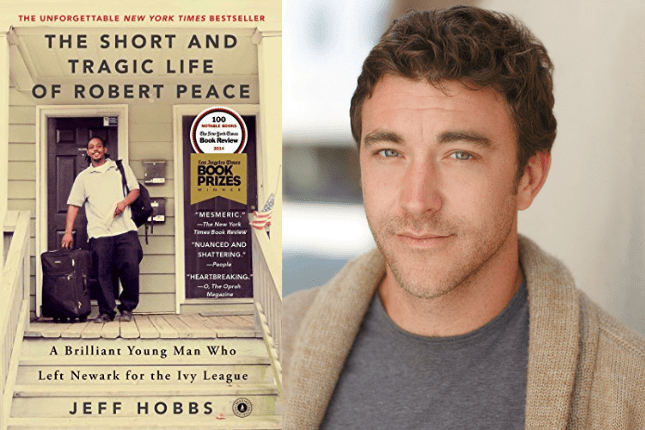

I’ve seldom read a book as riveting and ultimately devastating as The Short and Tragic Life of Robert Peace: A Brilliant Young Man Who Left Newark for the Ivy League. With deftly chosen detail and precision, author Jeff Hobbs chronicles the obstacle-ridden rise of Robert Peace, an intensely talented young black man, who went from inner-city poverty to the brink of promise offered by a Yale degree, the bill paid in full by a fairytale-like corporate benefactor impressed by his potential. But what comes next isn’t the inspiring uplift of a rags-to-riches story: it’s the harrowing fall and all-too-quick descent back into the illegal drug and deadly street culture that Peace never seemed to have truly escaped. Murdered at the age of 30, he became another casualty of the lure of the streets.

Long after finishing the book, I remain haunted by Peace’s fate. At what point, I keep wondering, could someone have intervened to change the course of this man’s life? And what would such an intervention—whether from friend or clinician or academic authority or mentor—have looked like?

Hobbs, a college roommate and friend, paints a portrait that offers a variety of clues and suggestions—all of which, unfortunately, spring to the fore only in retrospect. As a white, well-to-do suburbanite whose father was a surgeon, Hobbs is especially aware that there was plenty he never comprehended about the impoverished minority neighborhoods and crime-infested streets his friend came from. That makes Hobbs’s achievement all the more extraordinary as he dramatizes the drastic differences between his roommate’s raw, wounded neighborhood and the worlds of wealth and privilege represented by the landscape of Yale University.

To a casual observer—and to Hobbs, too, during their college years—Peace’s straight-A average suggested that he’d found a way to straddle those universes with uncommon ease. But in the aftermath of his death, it’s hard to escape the conclusion that Peace’s academic success only helped mask his inner turmoil. Throughout the book, the insidious undertow of the inner city is felt as a presence in the lives of Peace and his family—and so is the equally powerful desire to escape its grasp. Robert DeShaun Peace (known to his family as Shawn, to his Yale friends as Rob) was born in 1980 in Orange, New Jersey, an urban area just outside Newark with, Hobbs reports, “the second-highest concentration of African Americans living below the poverty line in America, behind East St. Louis.” About 1 in 30 residents became victims of violent crime each year.

Against this grim backdrop, with legitimate jobs scarce and a market for drugs insatiable, it’s sadly unsurprising that someone as smart and personable as Rob’s father, Skeet, thought nothing of supplementing his occasional day-job earnings by working as a drug dealer. What was more unusual in that setting was the close attention Skeet paid to his son, spending hours coaching him with his school work (father and son both possessed encyclopedic memories and high-level math aptitude) and proudly taking Rob with him on his rounds through his neighborhood turf. From Skeet’s point of view, he was showing his son how to act like a man, someone to be looked up to and respected, who also had the street smarts, charm, and guile to get out of a scrape, take care of his friends, and not have to worry about being snitched on.

Although Rob’s mother, Jackie, was glad Skeet took such interest in their son, she saw things differently. Fearful of being legally tied to someone whose unlawful activities risked endangering them all, she refused to marry or even move in with Skeet. She chose instead to remain a single mother and raise her son at her parents’ home. The example she set, she determined, would be an honest life, focused on education as the path to aspiration. To be sure, that meant working long hours at kitchen jobs that barely paid minimum wage, but it was legit, an honorable way to rise from poverty into the middle class.

With their disparate values, the two parents were “debating what kind of man they wanted their son to be,” Hobbs writes. A quick learner, whose daycare workers started calling him “professor” when he was 3, their son eagerly internalized both concepts. Reconciling those opposing visions would be another matter.

The event that would mark his life occurred when he was 7. His father was arrested for the drug-related murder of two young women in an apartment down the hall from his. The state asked for the death penalty; Skeet was sentenced to life behind bars. For the rest of his life, he maintained his innocence, and so did his son.

Rob’s self-protection against rage and despair seemed to be to wall it off, not talking about what had happened except to beg his mother to take him on the long trek to visit his father in prison. She did so, every two or three weeks throughout his boyhood, and when Rob grew old enough, he’d make the trip on his own. His loyalty was unshakable, and so was the barricade he constructed to block out any mention of this part of his life. He even kept from his mother the fact that, by the time he was in junior high, he’d begun assisting his father in an appeal that, in time, actually succeeded in releasing him from jail on the basis of a long list of prosecutorial errors. (What’s clear from the massive research Hobbs collected about the case is that, regardless of Skeet’s guilt or innocence, the police, his publicly appointed legal counsel, and the court system collectively failed to protect his rights.) It was a bitter victory, however: the reprieve lasted only 55 days, at which time a higher court reinstated the conviction. Skeet would die in jail in 2006 at the age of 59.

From boyhood on, Rob’s capacity to compartmentalize different aspects of his life went hand in hand with his chameleon-like ability to “front”—the word he used disparagingly to describe others he deemed were being inauthentic, merely playing to perfection whatever role was expected of them at a given time or place. And yet he himself excelled at wearing different personae. The good Rob was the caring son and grandson at home, the stalwart defender of his father, the pride of his school as number-one in academics and athletics, the natural leader his friends and classmates looked up to. This was the Rob for whom his mother scrimped to send to private school, and who showed her that her sacrifices had paid off when he got into Yale and captured the admiration of the wealthy benefactor who picked up his tab, no questions asked.

But split off from that front was the Rob who by the start of high school had started drinking, smoking dope, and picking up extra bucks by steering new customers to his dealer. It was this Rob who, once at Yale, quickly became one of the most prominent and popular dope dealers on campus. He spent most of his free time getting stoned or drunk, and he still aced all his classes, even with his highly demanding double major in molecular biophysics and biochemistry.

Hobbs writes that when Rob’s high-school swim coach asked him “why he smoked so much marijuana, why he would jeopardize his lungs, his mind, his future that way,” Rob became enraged and stomped away. For any other student, Rob’s behavior would have resulted in disciplinary action and, one hopes, necessary counseling. Instead, the “good” Rob got the benefit of the doubt, and the intimidated coach never broached the subject again. Similarly, when a Yale dean called Rob in to discuss his drug dealing, the conversation ended not with Rob’s suspension, or even a suggestion that he seek help, but with Rob making an empty promise, broken almost immediately, to cease his dealing.

It’s hard not to view these incidents as squandered opportunities that might have compelled Rob to begin to confront his inner demons. Instead, encounters such as these merely served to reinforce Rob’s belief that he’d always be able to charm trouble away with his future promise, and always succeed in deceiving his mother into believing that the money he brought home for her was from working at the dining hall at Yale, not from dealing dope.

All through school, Rob’s eyes and his mother’s had been on the prize of a college education, but with the diploma in hand, he no longer had a goal to shoot for. He’d been told by everyone around him from the get-go that he had promise, but no one had ever shown or modeled for him how to translate that intellectual and educational promise into a life that might hold meaning and satisfaction for him.

Although he talked vaguely of graduate school, Rob never applied. Instead, funded by a portion of his drug-dealing proceeds, he spent several months on vacation in Rio. When he returned home, he found that the cousin with whom he’d entrusted the rest of his money for safe-keeping had spent it all. Broke and adrift, he took a teaching job at his former high school and fell back in with old neighborhood friends who were also adrift. Over the next several years, his behavior became increasingly inconsistent and self-defeating. He quit his teaching job, dabbled in doomed real-estate schemes, and spiraled further down the employment ladder, working as a baggage handler at Newark airport until he was fired for refusing to take a mandatory drug test he knew he’d fail. He lost touch with most of his Yale friends, including Hobbs.

Ultimately, he turned to drugs as a full-time job, employing the lab skills he’d refined at school to grow designer marijuana in a friend’s basement in a grandiose scheme that he promised would bring in $1,000 a day. But he couldn’t charm his way out of the enmity he aroused in rival drug gangs, the most likely suspects in his murder.

The story of Robert Peace is provocative because we have no easy answers to explain the trajectory of his life. Hobbs introduces us to several of Rob’s friends from Yale and from Newark who also suffered devastating childhood poverty, who also benefited from educational scholarships to attend and graduate from college, and who also struggled with their own demons. The mystery lies not only in the thwarted promise of Peace, but in the resilience that allowed the others to follow through on theirs.

Diane Cole

Diane Cole is the author of the memoir After Great Pain: A New Life Emerges and writes for The Wall Street Journal and many other publications.