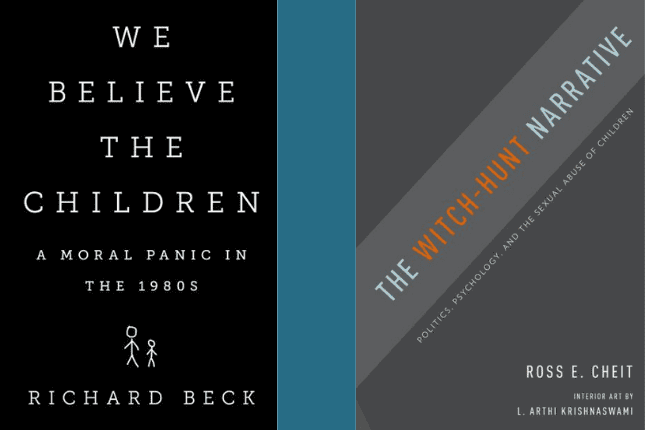

We Believe the Children: A Moral Panic in the 1980s

by Richard Beck

Public Affairs. 323 pages.

9781610392877

The Witch-Hunt Narrative: Politics, Psychology, and the Sexual Abuse of Children

by Ross Cheit

Oxford University Press. 544 pages.

9780199931224

The McMartin Preschool child sexual abuse case, a story that generated more controversy within the mental health field than any news story in the past 40 years, began in 1983 when a mother reported to the police that her two-and-a-half-year-old son had been sodomized by a male teacher at the school. The police took the charge very seriously. They identified a suspect and sent a letter en masse to the 200-some families whose children attended the school. In a tone all the more alarming for its matter-of-factness, the letter (from the local police chief in Manhattan Beach, CA) asked parents to question their preschoolers about any acts of “oral sex, fondling of genitals, buttock or chest area, and sodomy” they had witnessed or been subjected to. “Please keep this investigation strictly confidential,” the letter went on to state. Looking back, it’s hard to imagine a more incendiary way to inflame parental fears, and more missteps followed.

Over the next months, approximately 400 children were interviewed, using a battery of overtly leading questions and coercive techniques that constitute a textbook of how not to approach young children. Some of the children’s stories became increasingly strange over the course of the interviews, including accounts of their taking part in satanic rituals led by school personnel and witnessing gruesome animal slaughters. Saturation media coverage further sensationalized the story, pumping the primal fears of protective parents everywhere. Prosecutors out to make their political careers were overly aggressive, charging suspects on insufficient evidence, holding them without bail. And yet, after a pretrial and two separate trials that resulted in a hung jury, all charges were dropped.

This outcome was unsettling on many levels, especially after so much time (seven years from the initial report to the jury’s inability to reach a decision), money (the estimated cost of the prosecution was $15 million), and public outcry about children’s safety on every talk show and in every publication. What were people to make of it all? It raised justified doubts about the methods by which the children’s testimony was obtained—and subsequently did lead to the establishment of protocols in handling children’s disclosure, interviews, and testimony, as well as to stronger regulation of daycare centers. Credibility questions spilled over to various other preschool child-abuse cases that were making headlines in different locales around the country and, in the minds of a now skeptical public, melding into a single phenomenon, a witch-hunt that falsely targeted innocent teachers, ruining their reputations and wrecking their lives.

In addition, a highly critical spotlight was placed on the therapy profession itself. Were the therapists called in to consult on this case, as well as others around the country, too easily swayed by the unreliable memories and uncorroborated accusations of children and parents? Had sympathy for the children unintentionally led to suggestive questioning, tainted testimony, even the implanting of false memories? Therapists increasingly drawn into cases where “recovered” memories of childhood abuse stirred up intense family conflicts themselves asked whom they should believe in abuse cases filled with ambiguities. How were they to make sure they didn’t injure their clients or their families?

Some therapists took the critical jabs thrown them as valuable feedback, compelling the profession to be more objective when child abuse is disclosed, making sure not to rush to judgment, but to listen with disciplined, open-minded sensitivity. But others worried that neutrality taken to extremes carried another risk: making psychotherapists gun-shy about exposing the level of abuse that goes on in even ordinary families. Wasn’t it part of the therapist’s role to help children feel safe in speaking out?

Even 30 years later, these questions challenge us every time a new child-abuse accusation is made—and high-profile cases have been in no short supply these last decades. This may be why the debate over the McMartin case still smolders, as evidenced in journalist Richard Beck’s recently published essayistic, interpretive account, We Believe the Children: A Moral Panic in the 1980s. Beck views the era’s child-abuse cases from a cultural and political perspective. At their core, he says, they reflected an antifeminist backlash, in which working women (and working mothers in particular) were perceived as risking their kids’ wellbeing by placing them in a stranger’s care outside the home. The daycare “trials were a powerful instrument of the decade’s sexual conservatism, serving as a warning to mothers who thought they could keep their very young children safe while . . . pursuing a life outside the home,” he writes.

In addition, changing economic patterns—the 1980s was just the start of the global outsourcing that led to the loss of thousands of traditionally male manufacturing jobs—-further fueled male resentment of women’s newfound career success. With divorce rates rising and a growing acceptance of sexual experimentation and openness, it wasn’t just the male–female status quo that was being called into question, Beck asserts, but the very foundation of family life. And daycare became the scapegoat for all these tensions.

Once seen in this context, Beck says, the sex-abuse accusations can be understood as outward projections of deep-seated dread and anxiety of a changing social order that was threatening to upend the way we think of traditional nuclear family life. This, in brief, is the moral panic cited in his subtitle—another way of calling the accusations a witch-hunt. Like the original Salem witchcraft trials of the late 1600s, the McMartin-era daycare cases not only stemmed from baseless accusations, Beck says, but relied on the testimony of child witnesses who may not have been able to distinguish fact from fiction.

Among those who believed the children, of course, were many psychotherapists, whose profession doesn’t come off well in this book. In addition to criticizing mental health professionals’ handling of children’s testimony in the abuse cases, Beck debunks the recovered-memory movement, which developed in response to therapists’ work with clients who believed themselves to be adult survivors of child sexual abuse.

If you believe that most accusations of sexual abuse were part of a witch-hunt, then you’re also likely to believe that anyone tried or convicted in such crimes was an innocent victim caught up in the hysteria. Beck himself almost always sides with the accused, implicitly believing in his or her innocence. For instance, he paints a highly sympathetic portrait of Jesse Friedman, subject of the 2003 documentary Capturing the Friedmans. He believes that Friedman, who pleaded guilty in 1988 to 25 counts of sexual abuse and spent the next 13 years in prison, was unjustly convicted. Beck doesn’t mention that in 2013, the Nassau County District Attorney concluded, after a three-year reinvestigation of the case, that Friedman’s conviction was justified and proper. The report, as quoted in The New York Times, read, “By any impartial analysis, the reinvestigation process prompted by Jesse Friedman, his advocates and the Second Circuit, has only increased confidence in the integrity of Jesse Friedman’s guilty plea and adjudication as a sex offender.”

In an online blog, Brown University professor Ross Cheit, author of The Witch-Hunt Narrative: Politics, Psychology, and the Sexual Abuse of Children (published last year), lists additional omissions by Beck that, if included, would have weakened his contention that convictions reached in several other cases were unjustified.

Clearly, Cheit and Beck are at opposite ends of the argument, and Beck spends several pages of his book finding fault with Cheit’s book, a scholarly volume that refutes the whole notion of a witch-hunt phenomenon. Cheit’s goal in spending nearly 15 years systematically examining trial transcripts and interview tapes for the McMartin and other cases, he writes, was to put “the conventional wisdom to the test of the actual record.” In his 500-page study, he details what he discovered: that “a substantial number of the cases held up as ‘witch-hunts’ actually included credible evidence of abuse or even something stronger than that.” This means not only that the witch-hunt analogy is false, he says: its residual message can cause harm even now, leading people to doubt children who claim sex abuse and to distrust and dismiss their testimony. In fact, that is the message of Beck’s book.

It doesn’t work—or serve justice—to try to fit all the complexities of all the cases to confirm a theory, Cheit says. Weigh the evidence of each case individually to see where it leads. Proceeding this way, Cheit finds that the McMartin case was “unjust . . . to the defendants who were charged without sufficient evidence or adequate investigation,” as well as to children “brutalized by the judicial process.” Yet on the basis of his review of the evidence, he concludes that one of the defendants probably was guilty. That means that children who were molested, he says, “have been demeaned by the witch-hunt narrative’s assertion that the entire case was a ‘hoax.’”

Adhering to the witch-hunt narrative risks additional dangers: it “demonstrates the rise of what I call ‘disconfirmation bias,’ an approach to these cases that ignores evidence of guilt and exaggerates anything that might be construed as evidence of innocence,” Cheit writes. “Instead of a rush to convict despite the lack of evidence, there was now apparently a rush to acquit despite evidence of guilt.” But willfully turning a blind eye can be a close relative to denial.

In recent years, cries of a witch-hunt resounded when former Penn State football coach Jerry Sandusky was accused of the sexual crimes against children for which he was ultimately convicted. Allegations of a witch-hunt were also floated initially to deflect the onslaught of accusations and charges of child molestation perpetrated by Roman Catholic priests. In both cases, the witch-hunt allegation helped keep the truth under wraps, enabling high-level institutional cover-ups. In time, however, the preponderance of evidence proved the perpetrators’ guilt without question. While never overlooking the power even the most well-intentioned therapists have to do harm to clients and their families, we must recognize that it can often be easier to argue about witch-hunts than risk confronting the dark, unsavory reality of child abuse.

Diane Cole

Diane Cole is the author of the memoir After Great Pain: A New Life Emerges and writes for The Wall Street Journal and many other publications.