Enjoy the audio preview version of this article—perfect for listening on the go.

When therapists work with clients who don’t seem to respond to ordinary cognitive therapeutic approaches, it’s easy to feel stuck and frustrated. I know I’ve felt that way. After years of attempting to use talk therapy to help these clients alter their entrenched beliefs, I’ve discovered a more effective way to help them connect with their deepest experience—through the use of therapeutic rituals.

The hallmarks of talk therapy—insight, cognitive restructuring, and exploration of etiology—may not create change in clients who can’t seem to override their ingrained, unconscious patterns. In those cases, the amygdala, or emotional brain, may be running the show.

Since the emotional brain is nonverbal, sensory based, and symbolic, it’s not surprising that verbal, cognitive approaches aren’t always sufficient to create change. Because our emotional brain is geared to detect threats that are associated with past experiences, similar situations trigger involuntary responses. Although these responses may appear to be intractable, they can change in response to new, intense experiences that alter previous associations.

Healing rituals to alleviate emotional distress occur in many cultures. I first came across the use of therapeutic rituals early in my therapy career, when I was introduced to the work of Milton H. Erickson, the renowned psychiatrist and hypnotherapist, who sometimes designed unusual procedures and rituals for his clients to perform. Therapeutic rituals, of course, will vary according to each client’s individual situation. They may take the form of writing in a gratitude journal every morning, creating a collage of pictures of a deceased loved one, or burning a letter containing a narrative that doesn’t serve the client anymore.

I found that therapeutic rituals that engage clients’ unconscious world can help them develop a sense of agency and stability when they feel they have little control over their lives. In addition, rituals can act as corrective experiences as they create new meanings for past experiences while interrupting and altering preexisting emotional patterns.

I’ve worked with clients who, despite being effective problem-solvers, have a great deal of trouble accessing and working with their emotions. These clients often seem unable to understand why they can’t use their rational knowledge to override the emotions and beliefs that make them feel powerless. No matter how much logic and reason they apply to their problems, they still can’t seem to alleviate their emotional pain. Although it isn’t always easy to engage such people in therapy, I’ve found rituals can help. But here’s the challenge: how do you introduce rituals to such “logical” clients?

A Pattern of Fear

Henry, an engineer in his late 30s, came to therapy because of high levels of anxiety. He told me he didn’t know what was causing him to feel so anxious—which led me to think he might be dealing with generalized anxiety. In our first session, he was friendly and engaging, and we discussed some specific exercises, such as thought-stopping and progressive relaxation training, that he could use to deal more effectively with his anxiety. When he returned for his next session, however, his demeanor was different. Sitting on the couch across from me, he was stiff and unsmiling.

After a few minutes, he swallowed, cleared his throat, and said, “Doc, I wasn’t honest with you the last time I saw you. The truth is, I do know why I’m anxious all the time.” He paused. “I was embarrassed to tell you because it’s so illogical and silly, but I can’t escape it. I’ve been dealing with this for years and years.”

I leaned back in my chair, encouraging him to say more.

“As ridiculous as it sounds,” he continued, “I’m terrified of my stepmother, whom I haven’t seen in over 30 years. She’s a witch, and I swear she put a spell on me!”

With that confession, Henry began to tell me about his childhood between the ages of seven and ten, when he’d been physically and psychologically abused by his stepmother. He’d watch her privately cast spells meant to evoke dark spiritual forces that she believed would harm people who had caused her misfortune. Henry was forced to participate in these rituals and was made to stand in a dark room within a circle of candles as his stepmother chanted words he didn’t understand. Afterward, she smeared him with substances he didn’t recognize.

After the rituals ended, she’d warn him never to tell his father about what he’d seen and experienced. In fact, she repeatedly told him he’d be killed by demons if he ever told anyone about her witchcraft. Eventually, his father found out what she was doing and divorced her. “But even though she no longer lives near me, I’m still terrified that she could show up again and keep her promises to hurt me and my father.” He sighed. “It’s been over 30 years!”

Henry admitted he knew it was illogical—he was an adult who now lived on the other side of the country from his former stepmother—but he was still afraid of her. He had nightmares, checked the locks on his doors multiple times every night, and had nightlights in all the rooms of his house. “I sometimes wonder if my stepmother has already put a spell on me because I’m so trapped in fear,” he said. “It’s destroying my life.”

He stopped speaking so that he could compose himself, and then went on. “I even have trouble with relationships because I have a hard time letting my guard down with women. My mother died when I was four years old, and I remember little about her. If I could just be released from this fear, I think I might be able to trust more. I just want to be happy for once.” Henry’s voice trailed off.

As I listened to his story, I couldn’t help but feel moved. Henry’s early experiences with his stepmother had obviously created a pattern of terror and disempowerment that he couldn’t escape. Since he’d had no real closure from the experiences, his emotional brain continued to trigger the fear response, despite his attempts to reason his way out of it.

Defying Logic

I believed Henry needed a ritual to provide him with a safe structure to express the intense emotions he was still dealing with around his stepmother. When I construct a specialized ritual for clients, I make sure it’s unique to their situation and tailored to help them connect to their particular inner resources for healing. Since experience can change the actual structure of the brain, rituals that parallel the particular problems clients struggle with can create new and unique experiences to change the way their emotional brains relate to their difficulties. I don’t use rituals with every client. I primarily use them with those who have the ability to distinguish between reality and fantasy and who haven’t been able to make changes with traditional cognitive interventions. I wouldn’t use a ritual with clients who exhibited delusional or psychotic symptoms.

Many therapists might initially hesitate to utilize rituals in their therapy sessions because of a concern that a ritual may unintentionally reinforce their clients’ irrational beliefs. To the contrary, I’ve found that, when properly applied, therapeutic rituals can aid in interrupting clients’ automatic assumptions and provide them with mental and behavioral flexibility in approaching once-fraught situations in the future.

Because Henry’s attempts to use logic and reasoning hadn’t freed him from his frightening memories of his stepmother, I wanted to try a symbolic ritual to provide closure to Henry’s emotional brain. This ritual would also give him a sense of control over the part of himself that was still the scared little boy tormented by his evil stepmother.

“Henry,” I began during our second session. “Your situation is unique, but it’s one that I think we can change.”

Henry quickly looked up at me. “Really? You think so?”

“Yes. I think I may have a way out of this problem,” I said. “But I think we need to do something radical to stop the torment you’re feeling. What we have to do may challenge you in a way that you’re not expecting, but I believe we can destroy the grip your stepmother has had on your life. To be quite blunt, Henry, what I’m proposing won’t be easy at all, but I promise you that you’ll be safe.”

Because I felt that Henry needed to interrupt his persistent unconscious anxiety patterns, I believed that something akin to Erickson’s use of symbolic ritual could help him. My intuition told me that Henry needed to take a physical action that could show his unconscious mind that he could break free from his old fears. Even though he appeared to have relaxed somewhat after I assured him that his situation could indeed change, I remained a little apprehensive. Exactly what kind of intervention could I devise that would free Henry from the witch’s bondage?

The Ritual

When Henry showed up for our next session, he smiled tentatively as he sat down. “I have to admit I’m a little nervous about what’s going to happen today,” he said.

I returned his smile and nodded in encouragement. “Henry, you’re one brave man. Not only have you decided to face your fears, but you’ve agreed to do something challenging. You have real guts.” I looked into his eyes. “I appreciate your openness to this process, and I want you to know that we can stop our session at any time if you feel it’s best. I’m confident that when you leave here today, there will be a positive change, though I’m not sure exactly what that change is going to be.”

After Henry nodded, I handed him a blank sheet of paper. “I want you to write down every horrible thing your stepmother ever did to you. I want you to go into as much graphic detail as you can. I don’t want you to think about anything but getting all you can remember onto this paper. Take all the time you need.”

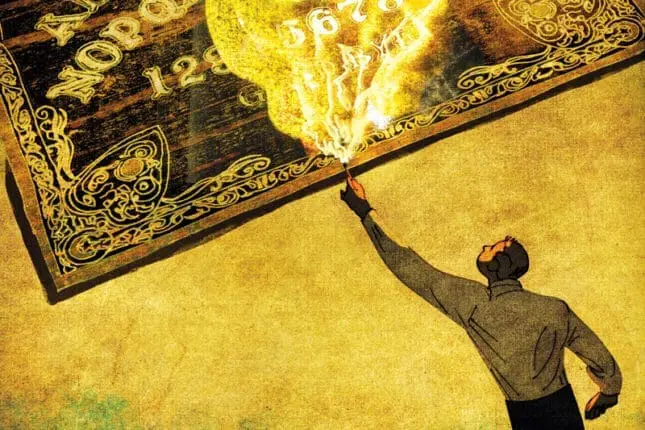

I sat quietly as Henry wrote for nearly 30 minutes. When he’d finished, I told him how much I admired his bravery and his desire to move forward with his life. I then brought out a roll of tape and a spirit board, which is a thin, flat board inscribed with the numbers zero to nine, the letters of the alphabet, and various words. This board is generally used by people who try to use spirits as tools to contact the dead. I’d purchased it for the purpose of a special ritual I hoped would help Henry.

When Henry saw the spirit board, he cringed. “Why in the world did you bring that board into the room?” he asked, his voice rising a little. “My stepmother used that thing and told me she was able to talk to evil spirits!”

I understood why Henry—the engineer and the man who’d been traumatized as a child—would quail at the idea of a spirit board. Other clinicians might have reservations, too. But I’d designed the ritual with careful thought about how to reach the place where Henry had been hurt. He needed to know at the core of his being that he was stronger than any spell that had been put upon him. Emotionally tortured by his stepmother’s rituals, he needed to perform an action that symbolically disconnected himself from her.

“Henry, as crazy as this sounds, we need to break the spell that your stepmother created,” I told him. “You’ve tried to solve this problem for years, but it persists. I know that the last thing you want to do is deal with this spirit board, but I think your unconscious mind is still frozen in terror because of what you suffered as a child.” I paused for a moment, letting him take it in. “This spirit board is now a symbol of all the horrible things you endured at the hands of your stepmother,” I said. “We’re going to use it to break free from her psychic clutches. You’ve tried everything else; why not go as far as we can to end your suffering?”

Henry thought for a long moment and slowly nodded. I handed him the tape and asked him to tape the paper containing all his stepmother’s tormenting actions onto the spirit board. After he did that, I asked him to go outside with me, taking the board with him. He followed me out the back door of my office building to a private area ringed by a stand of large trees.

“Henry, when you destroy this spirit board, I believe it will begin the process of severing your unconscious connection to your stepmother. I want you to demolish it any way you see fit, but I can’t help you. You have to do this on your own. This task will be difficult, but I know you can do it. I want you to take a minute to just look at what you’ve written on the paper taped to the board, and then do whatever you have to do to destroy the board.”

For a few moments, Henry looked perplexed. I wondered: would he go through with the task, or allow his rational side to talk him out it? But all of a sudden, he began to violently stomp on the board. He then picked it up and began slamming it against a tree. Even with all of this intense effort, however, the spirit board remained intact.

“Don’t give up Henry!” I shouted to him. “You can break this spell that’s been put on you!”

Henry glanced at me and nodded. He then leaned the spirit board at an angle against a tree and, using his entire body weight, jumped on top of it. With a loud crack the board broke apart, and he took each of the cracked pieces and broke them into smaller pieces.

When he’d finished, he looked at me with a smile. “Wow! That felt really good.”

I picked up all the pieces of the broken board and placed them in a plastic bag. I handed Henry the bag and said, “I want you to take the remains of this spirit board home with you, build a small fire, and throw the remains into it. Then take the ashes and mix them into the dirt around a new plant you’ll put in your yard within the week. Pick a plant that represents a sense of renewal to you. You’ve been brave to follow through on this task. After you plant your new flower or shrub, pay attention to anything that seems different to you.” Henry nodded. I turned and walked back into my office, leaving him alone in the secluded clearing with the debris of his ritual.

When Henry arrived at his next session two weeks later, he appeared much more relaxed than when I’d previously seen him. He smiled as he said to me, “Doc, it’s so bizarre! It just doesn’t make sense to me. A day or two after I burned the pieces of the spirit board and buried them under a rhododendron, I noticed that I wasn’t feeling as anxious as I typically have. I still have some fear, but it doesn’t overpower me like it did before. Two nights ago, I even decided to turn off one of my nightlights just to see if I could do it. I could! I also find that I’m not looking over my shoulder as much.”

Over the next few months, Henry began to report feeling less anxiety. He told me he felt less constant tension and was focusing better at work. I also noticed he was much more open to challenging his limiting beliefs. For example, when we talked about his hesitancy to start dating again due to his distrust of women, he was quick to acknowledge that his knee-jerk reactions weren’t realistic and were the results of old programming. Of course, he still struggled with restlessness and overthinking, but he eventually found that he didn’t need to come to regular therapy sessions because he’d begun feeling more at ease with himself. His story about his experiences with the witch didn’t change, but his story has a new ending—one in which he broke the witch’s spell and emerged victorious.

Practitioners interested in adding therapeutic rituals to their work need to bear in mind that while these practices are often helpful, they’re not standalone interventions. To be effective, rituals need to be used in conjunction with a solid therapeutic alliance and theoretical grounding. Keep in mind, too, that a ritual is not a one-size-fits-all intervention. What works for one client might not work for another. For a ritual to be transformative, it needs to be rooted in the client’s specific experiences. On the therapist’s part, designing a ritual requires keen attentiveness, careful planning, and a dash of creativity. When all those elements are in place, a ritual can be a powerful agent of healing.

Case Commentary

By Anita Mandley

I read Paul Leslie’s Case Study with curiosity and a smile. My curiosity was piqued because, in one way or another, I use rituals with almost all my clients, and I don’t often get a chance to hear the experiences of other clinicians who use them too. The smile came—and deepened—as I read about his work with Henry because it mirrored a lot of what I experience in using rituals with my clients and in my own life.

I had a client who used to experience flashbacks of horrific childhood abuse in the shower. He’d see the images on the shower wall and then get overtaken by terror and dissociation. The therapists he saw before me would tell him the images weren’t real or that he should take more medication to decrease or numb the panic and anxiety, which made sense on some level, but didn’t change that pattern. Together, we decided he’d experiment with filling a spray bottle with water and a little bleach. When he saw the images in the shower, he’d spray them and they’d dissolve. Finally, he experienced some power and control over those traumatic memories; and eventually, he was able to take showers without the images appearing on the shower walls. His ritual of preparing his spray bottle before the shower and spraying the images in the shower was healing.

Before he engaged in the ritual he’d designed for Henry, Leslie told him that he was brave even to try it, given that it didn’t exactly make sense to him. But I think Leslie should also be commended for his bravery, not only in proposing the ritual in the first place, but in having the courage to write about it, given that not all clinicians will see the wisdom of his ways. In my view, the ritual may not be seen as an evidence-based practice, but the outcome of healing is practice-based evidence.

Albert Einstein supposedly said, “The intuitive mind is a sacred gift, and the rational mind is a faithful servant. We have created a society that honors the servant and has forgotten the gift.” In this case, Leslie used his intuitive mind to construct a ritual for therapeutic purposes, addressing Henry’s specific wounds from childhood. Rather than any preconceived notion of healing, he took a risk and offered up an intervention you’ll never find in any therapy manual.

We all have transient identities—as counselors, therapists, social workers, psychologists, psychiatrists, or body workers. We come to this work with different degrees, areas of expertise, experiences, education, and training. Yet at our core, I believe our true calling is that of healers, no matter what that healing looks like.

I often hear about these sorts of interventions as a sort of last resort. They’re often seen as things we might try when more mainstream cognitive-based interventions haven’t worked. But my experience is that when they’re introduced early in the healing process, they can actually pave the way for more cognitive processing, problem solving, and behavioral change in the future.

Those outside-the-box interventions might be the place to start, not the place to try when all else fails. I think that’s especially true when the wounds occur in childhood or before the cortical structures have fully developed.

ILLUSTRATION BY SALLY WERN COMPORT

Paul Leslie

Paul J. Leslie, EdD, is a psychotherapist, author, and educator in Aiken, South Carolina. He’s a popular trainer in the areas of solution-based therapies, Ericksonian hypnosis, and creative psychotherapy applications.

Anita Mandley

Anita Mandley, MS, LCPC, practices at the Center for Contextual Change, where she focuses on clients who’ve experienced trauma. She’s the creator of Integrative Trauma Recovery, a group therapy process for adults with complex PTSD.