I don’t like to think about global environmental problems, and neither do you. Yet we can’t deal with problems we can’t face. Isak Dinesen wrote, “All sorrows can be borne if put into a story.” Here’s my story. In the cataclysmic summer of 2010, I experienced what environmentalists call the “‘Oh shit!’ moment.” At that time, the earth was experiencing its warmest decade, its warmest year, and the warmest April, May, and June on record. In 2010, Pakistan hit its record high (129 degrees), as did Russia (111 degrees). For the first time in memory, lightning ignited fires in the peat bogs of Russia, and these fires spread to the wheat fields further south. As doctors from Moscow rode to the rescue of heat and smoke victims, they fainted in their non-air-conditioned ambulances. In July, the heat index in my town, Lincoln, Nebraska, reached 115 degrees for several days in a row. Our planet and all living beings seemed to be gasping for breath.

That same month, I read Bill McKibben’s Eaarth, in which he argues that our familiar Earth has vanished and that we now live on a new planet, Eaarth, with a rapidly changing ecology. He writes that without immediate action, our accustomed ways of life will disappear, not in our grandchildren’s adulthoods, but in the lifetimes of middle-aged people alive today. We don’t have 50 years to save our environment; we have the next decade.

Nothing I’d previously read about the environment could quite prepare me for the bleakness of Eaarth. I couldn’t stop reading, and, when I finished it, I felt shell-shocked. For a few days, all I could experience was despair. Everything felt so hopeless and so finite.

During this time, my grandchildren came to visit. As we picked raspberries, I thought about all the care we lavished on the children in our family. We made sure they ate healthy foods and brushed their teeth with safe toothpastes. We examined and treated every little bug bite or scratch. And yet, we–and I mean all the grandparents in the world, including myself–hadn’t worked to secure them a future with clean air and water and diverse, healthy ecosystems.

Had we been in a trance? That summer, when I listened to friends talking about mundane details of life, I wanted to shout at them, “Wake up! Please wake up! Our old future is gone. Matters are urgent. We have to do something now.”

After years of being a therapist and a mother, I’ve learned that shouting “wake up” doesn’t work. One of my most dispiriting realizations was that while I wanted desperately to preserve the world I loved, I didn’t even know how to share this fact with my closest friends.

One night, my daughter and her family came for dinner during a record-breaking rainfall. After the baby went to sleep, we watched the wind whip through the pines and listened to the torrents of rain hammer our windows. Sara asked if my husband and I thought the rain was related to global climate change. Jim and I stared at each other, too confused to speak.

My wonderful daughter had the dreams all mothers have for their children. She was already doing her best. I couldn’t bear to inflict any pain on her. However, Sara was persistent in her curiosity. In the most positive, calm way that I could, I told her what I’d recently learned.

Sara was devastated. She and John quickly bundled up the baby and said good night. I could see her weeping as she tucked Coltrane into his car seat. I felt anguished, and I wasn’t sure I’d done the right thing. Yet Sara was 33 years old. Could I really shield her from what scientific experts were telling us? Would I want to be “protected” from the truth? Wasn’t it better if we faced these things together?

That next week, I couldn’t enjoy anything. My conversations with my husband quickly fell into what we call “the dumper.” I was afraid to be around friends for fear I’d infect them with my gloominess.

I knew I had to find a way out of my state of mind. I couldn’t survive with all that awareness every minute of my day. I wanted to be happy again, to be able to laugh, and to snuggle with my grandchildren without worrying about their futures. But I couldn’t forget what I now understood.

What pulled me out of my despair was the desire to get to work. I didn’t know what I was going to do. I felt unqualified for virtually everything involving the environment, but I knew I had to do something to help. It was unclear how much my action would benefit the world, but I knew it would help me. I’ve never been able to tolerate stewing in my own anxiety. Action has always been my healing tonic.

I invited a group of people to my house to discuss what we could do to stop TransCanada from shipping tar-sand sludge through our state via the Keystone XL pipeline. We called ourselves The Coalition. For more than a year now, we’ve met for potluck dinners and planning sessions. We’ve made sure the meetings have been parties. We’ve had wine, good food, and lots of laughter and hugs. We’ve tried to end our meetings on a positive note, so everyone would want to return. None of us has time for extra tedium or suffering, but we like working together for a common cause.

If you want to discover how the world works, try to change it–especially if the changes involve confronting the fossil-fuel industry. Our campaign has been a complicated story about money, power, international corporations, and politics. But it’s also a simple story, about my friends and me, working to save our state from what we nicknamed the Xtra Leaky Pipeline.

Through the year, we held rallies, educational forums, and music benefits, and set up booths at farmers’ markets and county fairs. In other words, we “massified”–a term we used to signify momentum and getting increasing numbers of people on board.

By the summer of 2011, our entire state had united around the idea of stopping the XL Pipeline’s route through our Sandhills and over the Ogallala Aquifer. Our campaign was the best thing to happen to our state since Big Red football. Progressives and Western ranchers worked together, and Sierra Club attorneys were given standing ovations in VFW halls in little towns with no registered Democrats. We staged tractor brigades and poetry readings against the pipeline. What all of us had in common was a desire to protect the place we loved.

As Randy Thompson, a conservative farmer who fought the pipeline, said, “This isn’t a political issue. There’s no red water or blue water; there’s clean water or dirty water.”

I wanted to keep Nebraska healthy for my grandchildren. When my grandson Aidan was 6, he had a growth spurt in his point of view. Our family had gone to a lake to watch the Perseid meteor showers. Afterward, driving back home, we crested a hill and Aidan saw the lights of his small town on the horizon. He said, “Look at my beautiful city.” I responded, “It’s a pretty town at night with all the twinkling lights.” Aidan was quiet for a moment and then said, “Nonna, my town is big to me, but small to the rest of the world.” I sighed. That’s a lesson we all have to learn sooner or later.

In a speech at a rally, I recalled that night. I told the crowd, “Aidan may be small to TransCanada. He may be small to our governor and legislators, but he’s big to me, and I’m going to take care of him.”

In January 2012, President Obama denied a permit to TransCanada because of concerns about Nebraska. But the outcome is uncertain, and we may yet lose our fight. We’re still working. John Hansen, head of the Nebraska Farmer’s Union, said, “Working for a cause isn’t like planting corn. You don’t throw in some seeds and walk away. It’s like milking cows, something you do over and over, and can never ignore.”

Our coalition isn’t about odds. When we started, we didn’t think we had a chance. We did it because it was the right thing to do, and we couldn’t let our state be destroyed without a protest. Our reward for this work has been a sense of empowerment and membership in what Martin Luther King, Jr., called a beloved community.

From this work, I’ve learned that saving the world and savoring it aren’t polarities, but turn out to be deeply related. As Thich Nhat Hanh writes, “The best way to save the environment is to save the environmentalist.”

George Orwell argued that pessimism is reactionary because it makes the very idea of improving the world impossible. I found that whether or not we believe we can change the world, even in a small way, acting as if we can is the healthiest emotional stance to take in the face of injustice and destruction.

——

“He who fights the future has a dangerous enemy,” said Søren Kierkegaard. Life is stressful. We think something is wrong with us, but the problems are endemic and systemic. As a people, we’ve lost our grounding in deep time and in our place. At root, our problems are relationship problems. We have a disordered relationship with the web of life.

Right now, the more we connect the dots between events, the more frightened we become. This reminds me of a night I slept in a tent with three of my grandchildren. Kate was 6, Aidan was 4, and Claire was 2. Claire and Aidan were blissfully happy. They snuggled and listened to the sounds of the cicadas and night birds. Meanwhile, Kate kept telling me she was scared and that she wanted to sleep in the house. Stupidly, I chided her for her fears. I asked, “Kate, you are the big sister and the oldest. Why can’t you be as brave as your sister and brother?” She wailed, “Nonna, they’re little. They don’t know enough to be scared!”

These days, I often feel like Kate did that night. I know too much about deforestation, nuclear power plants, our tainted food supply, and our collapsing fisheries. Sometimes I wish I didn’t know all these things. But if we adults don’t face and come to grips with our current reality, who will?

Neither individuals nor cultures can keep up with the pace of change. Recently I was telling my grandchildren about all the things that didn’t exist when I was a girl. I mentioned televisions (in my rural area), cell phones, the Internet, cruise control, texting, computerized toys, laptops, video recorders, headphones for music, and microwaves. The list was so long that my grandson Aidan asked me, “Nonna, did they have apples when you were a girl?”

We’re bombarded by too much information, too many choices, and too much complexity. Our problem-solving abilities and our communication and coping skills haven’t evolved quickly enough to sustain us. We find ourselves rushed, stressed, fatigued, and upset.

On all levels–international, national, and personal–many situations now seem too complicated to be workable. A friend of mine put it this way: “There are no simple problems anymore.”

In addition to the problems that we can describe and label, we have new problems that we can barely name. Writers are coining words to try to describe a new set of emotions. For example, Glenn Albrecht coined the term solastalgia to describe “homesickness or melancholia when your environment is changing all around you in ways that you feel are profoundly negative.”

We experience our own pain, but also the pain of the earth and of people and animals suffering all over the world. Environmentalist Joanna Macy calls this pain “planetary anguish.” We want to help, but we all feel that we have enough on our plates without taking on the melting polar ice caps or the dying oceans.

One night before dinner, Jim asked me to sit and have glass of wine with him. That day, he’d overseen the installation of a heating and air-conditioning system after a tree had crushed our old one. That same week, our refrigerator had needed replacing. And suddenly our dishwasher wasn’t working properly either. I’d been writing about global climate change and working with the Coalition to Stop the XL Pipeline. I said, “I’ll sit down with you as long as we don’t have to discuss the fate of the earth.” Jim agreed readily and added, “I don’t even want to discuss the fate of our appliances.”

The climate crisis is so enormous in its implications that it’s difficult for us to grasp its reality. Its scope exceeds our human and cultural resilience systems. Thinking about global climate collapse is like trying to count two billion pinto beans. Oftentimes, because we don’t know how to respond, we don’t respond. We develop “learned helplessness” and our sense that we’re powerless becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy.

In States of Denial, Stanley Cohen writes about Germany and the denial of the Holocaust. He talked about a state of knowing and not knowing that arises in ongoing traumatic situations. This “willful ignorance” occurs when information can’t be totally denied, but can’t be processed either. That’s the state I think we’re in now when we try to deal with global climate change.

We live in a culture of denial. A Pew Research Center poll in September 2011 revealed that, in spite of increasing evidence, belief in climate change was at its lowest level since 1997. In fact, belief had decreased from 71 percent to 57 percent in the previous 18 months. Even the manner in which we discuss climate change is odd. We don’t talk about “believing in” the laws of aerodynamics, the DNA code, or faraway galaxies. By now the evidence for global climate change is solid and the scientific community is united. So why do we speak of believing in it as if we were speaking of belief in extraterrestrials?

Partly these poll numbers reflect a well-funded and orchestrated misinformation campaign by the fossil-fuel industry. Robert Proctor at Stanford University coined another new word, agnotology, for the study of ignorance or doubt that’s deliberately manufactured or politically generated.

The poll results also can be explained by what Renee Lertzman called “The Myth of Apathy.” She interviewed people about global climate change and found that they actually care intensely about the environment, but that their emotions are so tangled up and they’re so beset by internal conflicts that they can’t act adaptively. They aren’t apathetic, but rather shut down psychologically.

All cultures have rules about what can and can’t be acknowledged. This reminds me of an old joke about the Soviet Union. Two KGB men were walking together down the street. One of them said to the other, “What do you think of this system?” “I don’t know,” said the other one. “I probably think about the same as you do.” “In that case,” said the first, “I’m going to have to arrest you.”

Social and environmental studies professor Kari Norgaard writes, “The denial of global warming is socially constructed. In America it is almost as if relevant information about our climate crisis is classified. Our national policy towards the devastation we face is, ‘Don’t ask. Don’t tell.'”

We all have a healthy and understandable desire to avoid feeling pain. We want to savor the occasional shrimp cocktail without thinking about the ruined mangroves or read a book about lions to children without wondering how many are left in the wild. Yet we cannot solve a problem we will not face.

Once we face the hard truths about our environmental collapse, we can begin a process of transformation that I call the “alchemy of healing.” Despair is often a crucible for growth. As we expand ourselves to deal with our new normal, we can feel more vibrant and engaged with the world as it is.

We can be intentional when we’re shopping, planning a trip, or working in our communities. We can be citizens of the world, rather than consumers, and we can vote every time we hand over our debit card.

We’re all community educators whether we know it or not. Everything we say and do is potentially a teachable moment for someone. So appoint yourself a change agent, engage in participatory democracy, and help yourself, your country, and your world. Belief often follows action. The harder we work, the likelier we are to experience hope and to improve our situation.

Amazement is another antidote to despair. Author Hannah Tennant-Moore wrote, “It took me a long time to learn that being miserable does not alleviate the world’s misery.”

After a rough week, I felt compelled to drive to Spring Creek Prairie, about 30 minutes from my home. I joined a group of birders doing a winter bird count. It was a grand experience, with long lines of snow geese overhead, woodpeckers in the burr oaks, and a mink ice-skating in the little pond. However, at some point, I wanted to be away from people, even the birders I normally enjoy.

I walked alone to a sunny patch of prairie, lay on the ground, and looked at the sky through the waving big bluestem. I imbibed the prairie. I felt the warm earth beneath me. I smelled the moisture, the dirt, and the cereal-like aroma of the tall grasses. I looked up through the golden seed heads at the blue sky and the geese. I heard their calls and the wind rustling in the grasses. As I lay there, I thought, “I’m getting what I most needed today.”

I’m lucky to have a prairie nearby, but we all have green space available to us. We all can look at the sky. As my friend Sherri said, “I’ve never seen an ugly sky.”

Another day, Margie brought her dog over for a walk around the lake. When we returned to my house, Leo began rolling around in the grass. First, he rolled on his back; then he lolled about on his stomach, trying to have every possible inch of skin touching the grass. Margie said, “If you want to know the time, ask a dog. They always know, and they’ll tell you the correct time, which is now, now, now.”

Transcendence can come from work, bliss, or an expanding moral imagination. I define the moral imagination as the ability to understand how the world looks and feels to another person. It involves motivation, heart, and imagination. My respect for the moral imagination leads to a simple value system–good is that which increases it and evil is that which decreases it.

I believe that the purpose of life is to expand our own moral imagination and to help others expand theirs, so that our circle of caring, which begins with our families, eventually includes all living beings.

One day, I played my grandchildren a song called “Hey Little Ant” by Phillip and Hannah Hoose. This song is a conversation between an ant and a boy on a playground with his friends watching. He wants to squish the ant just for fun. But the ant sings that he has a home and a family, too. He sings to show the boy that his life is as precious to his ant family as the boy’s life is to his human family. The song ends with a question for the listener to ponder: “Should the ant get squished? Should the ant go free? / It’s up to the kid, not up to me. / We’ll leave that kid with the raised-up shoe. / Now what do you think that boy should do?”

When 9-year-old Kate heard it, she said, “Nonna, I’ll never squish an ant again.” Aidan, who was 7, also promised to let all ants run free. But 5-year-old Claire said, “Nonna, I still like to squish ants, but I won’t kill any talking ants.” Sigh. She’ll have a growth spurt soon enough.

Poet Pablo Neruda wrote, “We are each one leaf on the great human tree.” I hope we can extend that to include all living beings.

Dealing with our global crisis is essentially an ethics problem. If we don’t expand our moral imaginations, we’ll destroy ourselves. Healing will involve reweaving the most primal of connections to this sacred web.

Interconnection can be seen as a spiritual belief, especially in Buddhism. As Thich Nhat Hanh says, “we inter-are.” But it’s also a scientific fact. Economist Jeremy Rifkin writes, “We are learning that the earth functions like an invisible organism. We are the various cells of one living being. Those who work to save the earth are its antibodies.” At its core, interconnection is a survival strategy. Gregory Bateson said it best, “The unit of survival is the organism and his environment.”

The next great rights battle will be a fight to rescue our beleaguered planet. It’ll be about air, plants, animals, water, energy, and dirt. We have a right to a sustainable planet and a future for our grandchildren. And the meadowlark, the fox, the bull snake, the mosquito, and the cottonwood also have this right.

We’re in a race between human consciousness and the physics and chemistry of the earth. We can equivocate, but the earth will brook no compromises.

In our great hominid journey, no one really knows what time it is. We could be at its end, or we could be at the beginning of a great and glorious turning toward reconnection and wholeness.

We who are alive today share what Martin Luther King, Jr., called “the inescapable network of mutuality.” We aren’t without resources. We have our intelligence, humor, and compassion, our families and friends, and our ancestry of resilient hominid survivors. We can be restored.

Since the beginning of human time, how many people have loved and cared for each other in order for us to be alive today? How many fathers have hunted and fished, fought off predators, and planted grain so that we could breathe at this moment? How many mothers have nursed babies and carried water so that we could savor our small slice of time?

We can never know the significance of our individual actions, but we can act as if our actions are significant. That will create only good on earth. Besides, what’s our alternative?

As U.S. Poet Laureate W. S. Merwin said, “On my last day on Earth, I’d like to plant a tree.”

So let’s save and savor the world together.

I wish you well on your journey.

Illustration © Jerry Silverberg / Sis

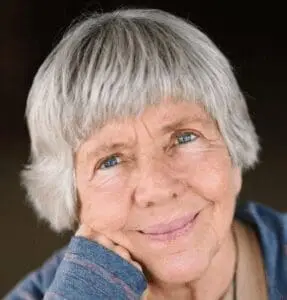

Mary Pipher

Mary Pipher, PhD, is a clinical psychologist, author, and climate activist. She’s a contributing writer for The New York Times and the author of 12 books, including Reviving Ophelia, Women Rowing North, and her latest, A Life in Light. Four of her books have been New York Times bestsellers. She’s received two American Psychological Association Presidential Citation awards, one of which she returned to protest psychologists’ involvement in enhanced interrogations at Guantanamo.