In 1972, I was drafted into the Army. Fortunately, I wasn’t sent to Vietnam. Instead, I was assigned to a Georgia stockade to work in what was then called mental hygiene, even though I had no idea how to do therapy. When I asked the fort’s psychiatrist for a book that would help my work with the prisoners, he recommended Jay Haley’s Strategies of Psychotherapy. For someone interested in human psychology, reading this introduction to therapy was like learning magic. I found out later that the psychiatrist hadn’t recommended the book because I’d been giving off some sort of wise, alchemist vibe, but simply because Jay Haley and I shared a first name and the psychiatrist thought it was funny.

In those early days, family therapy wasn’t being taught in graduate school. The concept that families were the patient—the symptom bearer—was a new phenomenon, and the practice only really existed in training institutions. Family therapy training centers were popping up all around the country, each one a draw for aspiring family therapists. As my time in the Army came to a close, I told myself, “Someday I’ll go to the Philadelphia Child Guidance Clinic!” The fact that it was almost 700 miles away hadn’t sunk in. And it didn’t need to, because geography and fate had other ideas.

After graduate school, I found myself working as a family therapist at an alternative high school in Collingswood, New Jersey, just miles away from “The Clinic.” So I applied to its extern program. When I was called in for an interview, I found out that my interviewer was none other than Marianne Walters, a feminist pioneer and architect in the family therapy movement, who’d worked closely with Salvador Minuchin, Braulio Montalvo, Jay Haley, and other family therapy gurus. I was awestruck. Toward the end of the interview, I braced myself for the worst. “You’re too young,” she said with a wise smile. “Come back next year.” And so I did. But when I came back, I learned from the secretary that Dr. Minuchin would be my interviewer. Oh my God! I thought. Why did I have to wear a flannel shirt today? He’ll see all the sweat! Before I had more time to think about my poor choice in clothing, the door to Minuchin’s office swung open. There he stood, smoking a cigarette. Somehow, I survived the interview and was invited into the extern program—flannel shirt, ponytail, and all.

On my first day, I walked with amazement through the clinic’s halls. I’d spent years only reading about the place. I’d never seen before—and haven’t seen since—an institution that offered so much. There was a big, carpeted pit in the waiting room surrounded by couches, a playroom with a “play lady,” who’d watch the children when the therapist needed to talk to parents alone, an inpatient unit with two apartments to hospitalize entire families, a school and preschool, a basketball court, a library, and a media center with hundreds of videotapes of sessions that you could pick off the shelves and look at whenever you wanted. Every treatment room had a one-way mirror with video cameras to film sessions, and phones on both ends so the therapist could be called with suggestions that could help a family break through their stuckness. One room had a control center that could be used to rotate cameras, do close-ups, and broadcast live. We were even given beepers—a big deal at the time! It felt like some sort of family therapy Disney World, and we all had day passes.

In 1978, I was invited to join the clinic’s faculty. But I felt woefully inferior, sometimes sitting shoulder to shoulder with people I’d only read about: Salvador Minuchin, Braulio Montalvo, Charles Fishman, Peggy Papp, Marianne Walters, and, for two residencies, Carl Whitaker. In meetings, I’d pretend I was an armchair, trying to blend in and hoping nobody would notice me. Sometimes I’d pinch myself. What am I doing here? I wondered. How did I get so lucky?

It was hard not to feel as if we were part of a larger revolution, one that was going to change therapy and the world as we knew it. Systems thinking and its offshoot, family therapy, challenged how therapy had been done for so long. Traditionally, patients were “on the couch,” and the therapist was heard but not seen. In family therapy, instead of talking about the family, the therapist was in the room with the family.

We were taught to pay special attention to the concept of joining, to search for patterns and strengths, and to enact those processes in the here and now. We looked at the effects of eating disorders, substance abuse, divorce, and foster care. The staff hierarchy felt flattened and the work collaborative. In systems thinking and Structural Family Therapy, context counts. Because of its reputation, the clinic had achieved global renown, but its heart and roots remained in south and west Philadelphia, serving poor and minority families.

It was from those communities that Minuchin and his colleagues hired two dozen “natural healers” to collaborate on developing Structural Family Therapy. Social justice was a priority. Working with and being supervised by some of the same natural healers opened my eyes to the importance of attending to systems, to what it really meant to be a family, in all its multiple contexts.

Still, I wasn’t immune to getting stuck.

Not long after getting hired, I was watching a session through a one-way mirror, joined by a group of trainees I was supervising. The father sported dark sunglasses, combat boots, and a Sherlock Holmes coat and hat. The mother sat quietly next to him. Their son, about eight, sat silently in a big puffy coat. It was their first time at the clinic, and things weren’t going well.

“What’s your degree?” the father barked at the therapist. “How long have you been doing this?”

The therapist, easily a decade older than the man and very capable, tried to hold his own, but the father kept coming after him. I could tell he was shaken.

“Seriously, what are your credentials?” he hammered.

My trainees began to look at me as if I was going to come up with some amazing intervention, but I had no idea what to do. I told the group I was going to step out for a moment.

At the clinic, you never knew who you’d bump into in the hallway, but you could always count on snagging someone to get their perspective. That day, just by sheer luck, it was Braulio Montalvo.

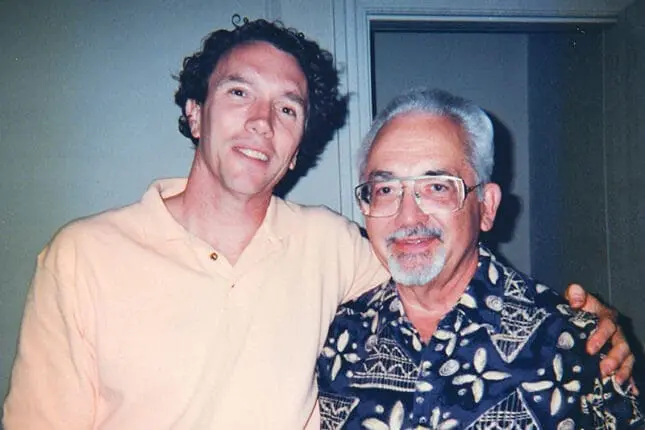

Braulio was one of the senior staff members who’d been at the clinic since the 1960s, and we’d gotten to know each other over the years, bonding over boxing, Muhammad Ali, cartoons, and my constant amazement at his thinking and supervision. If Salvador Minuchin was our father figure, Braulio was our uncle, the one who’d say, “Yeah, you can do that, but you don’t have to either.”

“Braulio!” I said, running up to him. “Please, would you just come in and take a look at this family? I don’t know what the hell I can do to help. This father, he’s dominating the conversation, not letting his wife and son get in a word. Please have a look.” I knew he liked coffee, so I decided to be strategic. “I’ll buy you coffee forever!”

“Okay,” he replied in his thick Puerto Rican accent, “I’ll take a look.” With a grin, he added, “And I’ll take the coffee too.”

Back behind the one-way mirror, I watched as he entered the therapy room and introduced himself. This kind of interruption was something Minuchin had come up with—a way of tipping sessions past a homeostatic threshold by introducing something new. It was also a way of giving the therapist a cue to take the therapy in a particular direction.

Braulio quickly joined with the father. I was struck by how complimentary he was.

“I notice you have a lot of ideas,” he said to the man. “And I can see you’re very concerned about your son and his welfare.”

The man nodded.

“It’s an important job, being a husband and a father. And I can see you’re a strong man, too. Now, are you strong enough to listen to your wife and son?”

It was brilliant sleight of hand. Braulio had created an interesting paradox. The father, who’d been talking incessantly, now stopped to think. “Yeah,” he said with a nod.

Braulio wasted no time. “Good!” he said. “Because it’s important that they be heard as well. It takes a strong man to do that.”

Sensing they now had space to speak, Braulio stepped out of the room. The wife began to talk. Then the son, too, while the father and therapist listened.

I looked at my students. We all had our mouths open. It was the most amazing thing we’d ever seen. In under two minutes, Braulio had turned the session on its head, changed it from individual therapy to family therapy, from symptom to system. His capacity to read and transform a stuck situation had been nothing short of miraculous.

When I thanked him later that day, I asked him what his secret was.

“You have to be careful how you talk to clients who challenge you,” he told me. “It’s easy to slide into an escalating cycle of one-upping each other. All you have to do is find a way to acknowledge that the father had this strength, this untapped capacity to listen, and use it in a different way.”

It was classic Braulio. He was like an artist who found beauty in the ordinary. I remember once, a bright but overconfident young psychiatrist was describing a tricky case, going on and on in magnificent detail about how he’d handled it.

After he’d finished, the psychiatrist turned to Braulio. “So, Braulio, what do you think?”

Braulio paused and smiled. “I think you don’t have to go around the block to cross the street.”

Everyone in the room loved that.

Today, when I think back to my clinic days, and to that session with Braulio, I still pinch myself and think, Did that really happen? There’s never been anything quite like it since. People like Minuchin, Montalvo, Haley, Walters, and so many other talented and wise supervisors made the clinic what it was—and helped make family therapy what it is today. They inspired a generation of therapists to think in ways no therapist had before—which was necessary, but not sufficient. As Minuchin told me in an interview several years before his passing, “We thought we were going to change the world one family at a time, and we were wrong.” He, too, realized the importance of the larger context.

In the mid-’90s, the Philadelphia Child Guidance Clinic closed for good, squeezed by high rent. It lives on in the Philadelphia Child and Family Therapy Training Center and the Minuchin Center for the Family. Both offer family and systems-based training and consultation. As for me, I went on to open a private practice and taught at Penn and Drexel universities. I continue to apply strength-based structural and systems principles to my clinical work, supervision, and consulting.

Certainly, things have changed. Today’s graduate school courses tend to be more of a theoretical tapas, in which students sample different models to see which fits them best. While students still learn by doing, it’s likelier to happen at their field placements, which may or may not be family or systemically focused.

Personally, as a family therapist, I sometimes feel like a village blacksmith still shoeing horses, shaking my fist at people driving past in those newfangled automobiles. That said, I believe there’s still a place for family therapy in today’s world, and some excellent training programs are available. With renewed focus on racial justice and equity, we’re understanding more and more just how much individuals and families are embedded in the larger social context. Strength-based, structural approaches and family-based practices are still useful and can help move these progressive agendas forward. Now is the time for us systemic old-timers to pass along our stories so that the next generation can write theirs.

Braulio once said family therapy allowed us to see people in a new light, that it expanded the possibilities for how we understand human behavior. That’s as true now as it was then.

*Jay Lappin and David Lappin—no relation.

Jay Lappin

For more than forty years, Jay Lappin, MSW, LCSW, has been helping families, couples and individuals navigate life’s transitions to create strong, sustainable relationships. Trained in the relational architecture of Structural Family Therapy by Dr. Salvador Minuchin, he has worked with, written and taught professionals and the public how to become empathic and effective problem solvers. Jay’s work on family therapy, couples therapy, diversity and large systems of care has been published in professional journals and texts and he has been quoted in popular magazines and newspapers such as Cosmopolitan, Self, USA Today, The Philadelphia Inquirer, and The Courier–Post. He’s a former Contributing Editor for the Psychotherapy Networker.