Enjoy the audio preview version of this article—perfect for listening on the go.

Often when people ask about your self-care, what they really mean is, If you were taking proper care of yourself, you wouldn’t be suffering from burnout.

The (usually) unintentional implication is that you are the problem, that you are the one who should (or even could) put a stop to your suffering. This felt sense of judgment is an especially common experience for people who work in helping professions and other occupations that have historically been more male dominated, like science and medicine. It’s also common for students and trainees working toward licensure/certification (e.g., medical residency or clinical internship) to report trying to keep their burnout symptoms and treatment efforts private, especially if it has to do with mental health, because struggles with mental health and wellness are frequently seen as weakness.

As a therapist, one of my specializations is supporting health and helping professionals struggling with burnout, people who work as surgeons, nurses, emergency department staff, social workers, and even other therapists like me. Many of these people spend years and years studying human bodies. They know what needs to happen for proper care—often they even manage it for themselves pretty well. They’re already paying attention to sleep hygiene. They’re staying hydrated and nourished. Many are trying combinations of joyful movement and meditation. They’re sitting through the yearly “not mandatory” burnout workshop scheduled during lunch break (which is justified by including a pizza lunch). It’s often through sobs that they give me the long list of everything they’re already doing, everything they’ve already tried, to get some relief, only to conclude that nothing really seems to help.

Under the weight of hopelessness, it gets easier to believe negative thoughts about yourself. Of all people, with all your knowledge and training and experience—after everything you fought to overcome—you should be able to pull yourself together! This is how I’d distill the big struggle that comes up again and again for so many helpers.

A large part of solving the problem of burnout is sorting out how to work smarter, not harder. As you increase your understanding and awareness, make some plans, and conduct a few mini-experiments, you can start feeling more ease, wholeness, and joy—and less burnout. A few shifts, changes, and reframes are going to help make things feel easier.

Another big part of burnout relief is acknowledging the fact that the game is rigged, as burnout researchers Emily Nagoski and Amelia Nagoski say. Our systems, to a large extent, have depended on exploitation, especially of marginalized and minoritized people. Without an appreciation for context, history, power, and oppression, you run the risk of blaming your burnout symptoms on yourself. You have to be able to recognize what’s normal for our human family—including limitations!— so that when you’re being expected to be super-human or robot-like, you can at least recognize and acknowledge the unfairness.

Singer-songwriter, podcast host, and author Michael Gungor, says, “Burnout is what happens when you try to avoid being human for too long.” This principle even applies to our work as therapists.

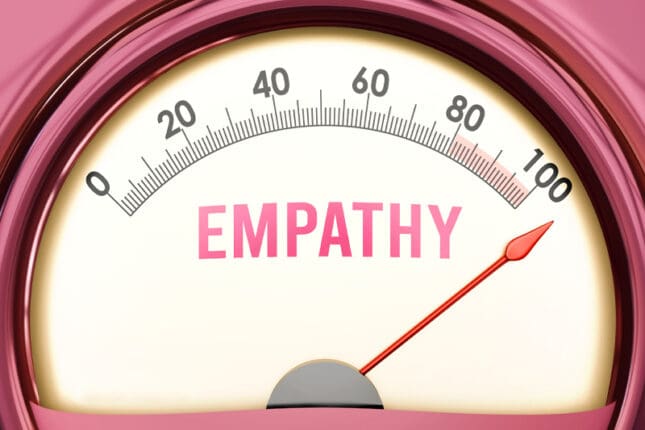

Figure out Your Empathy Dial

Where I live, to get licensed as a counselor, you need to complete at least two internships: one shorter pre-grad internship while you’re still in school, and a second 3,000 hour post-grad internship working under a supervisor after you finish. As I was completing my internship hours, I started coming unraveled around hour 1,200. My cynicism was through the roof—it was dancing on the roof. Talk therapy was helping but not really putting much of a dent in the irritating combination of apathy and frustration that was covering me all over like sap. Every morning for months I would wake up, make coffee for my partner and me, and then vent and complain to him about the exact same things in an endless loop until the coffee was gone. One thing about burnout that’s rarely addressed—because typically burnout pulls our focus to ourselves—is the way it can leak onto those who love and support us—our lovers, family, children, colleagues, clients…. I was sick of feeling at my wit’s end all the time and feeling guilty for basically bringing my burnout, like a third person, into my relationship.

At the same time, I had to keep going if I wanted to become fully licensed and open a practice, as I had planned for so long. And the longer it took, the longer I was paying monthly dues to my supervisor. One thing I had to do to keep myself from burning out was figure out my empathy dial. In her book Help for the Helper, celebrated therapist Babette Rothschild introduced the idea of an “empathy dial.” Imagine the volume knob on a record player, or something from the 1960s—it can be dialed all the way down to 0 to be silent, or blasted all the way up to 10. Lower volumes are softer and gentler; louder ones can ring your ears.

Imagine blasting your empathy dial at 10 constantly. Especially if your work involves caring for other humans for a long period of time (which is certainly the case for therapists), blasting at top volume will burn you out. This doesn’t mean that you never turn up your empathy, only that you have to figure out how to dial it up and down with balance, so that you have something left at the end of the day for yourself and your loved ones.

You can begin to figure out your empathy dial by reflecting on these five areas:

Embody healthy compassion. As a person, if you are set to 0 on the empathy dial, you don’t feel any of what someone else is feeling. If you’re dialed all the way up to 10, you are empathizing with them as much as humanly possible—feeling what they are feeling right along with them. Staying dialed up to 10 all the time isn’t sustainable. You have to figure out how to embody a healthy compassion and care, dipping into high empathy only when needed in your role/context.

Discern between empathy and support. Can you tell the difference between when you’re empathizing with someone—feeling a bit of what they are feeling with them—and when you’re compassionately supporting them: feeling for what they’re going through without experiencing through empathy the full-on emotions, sensations, and kinds of thoughts they themselves are feeling? If yes, how can you tell the difference? What do you notice about your body and mind when you’re in each different mode? If no, what can you pay attention to that will help you learn the difference?

Understand your blocks to empathy. When is it easiest for you to empathize with someone? When is it hardest? When is it hardest to try to dial down how much you are empathizing with someone? (For example, “It’s hardest when someone is angry and being harsh or cruel,” or “It’s easiest to empathize with patients going through what I’ve experienced myself,” or “It’s hardest to dial it down when it’s my child, spouse, or loved one.”)

Consider the impact of role and context on empathy. Think about your role or context and the times when you’re called to care for someone who is in pain and/or distress, because of work, school, or home life. Choose a recent, special example. What would it have looked like if you had dialed empathy in to 0? All the way up to 10? (For example, “If I was at 0, I might be dissociated and numb but moving my eyebrows to look concerned—like the porch light is on but no one is home,” or “I might be short and sound irritable,” or “If I was all the way at 10, I might be crying along with the hurting person—they might ask me if I’m okay.”)

Recognize signs that it’s time to dial down. If you accidentally leave your empathy dial too high for too long, what do you notice mentally? Physically? Relationally? How can you tell when it’s time to think about dialing it down for more balance? (For example, “I start to dehumanize patients and see them more as bodies than people,” or “I am more impatient with my kids and pets in general,” or “My GI issues start acting up,” or “My partner and I get into conflict more often.”)

When my heart was hardening as I completed my post-graduate clinical hours, bringing awareness to how my empathy dial worked played an important role in decreasing my cynicism and distress. Many clients also report experiencing improvements as they draw on this concept of the empathy dial. At the same time, it’s important to keep in mind that anger and frustration (feelings that often accompany burnout) get talked about as if they’re less valid or noble than feelings like sadness. In discussing ways to reduce frustration or shift your experience of burnout, I don’t want to suggest that the goal is simply not to be frustrated. Frustration, like other messengers your body uses, is there to communicate with you—to help you make sure your needs are met. There are times when anger will help you realize exactly what it is you need, or which step to take next. If you work on being aware and intentional with your empathy dial and yet you still notice righteous rage shining through a lot, it’s worth examining the possibility that you are in an unjust situation.

Adapted from 8 Keys to Healing, Managing, and Preventing Burnout, Copyright (c) 2025 by Morgan Johnson. Used with permission of the publisher, Norton Professional Books, a division of W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.

Morgan Johnson

Morgan Johnson, LPC, is an author, speaker, and psychotherapist based in Fort Worth, Texas. She provides counseling services primarily for individuals healing through clinical burnout.