The bad news was made official in 2010, though everybody in the head-shrink business had long suspected as much: psychotherapy was in decline, or even in freefall. According to a study published in December of that year in the American Journal of Psychiatry, the proportion of people getting only psychotherapy in outpatient mental healthcare facilities had fallen from 15.9 to 10.5 percent between 1998 and 2007—that’s by more than a third—while those receiving both therapy and meds had fallen from 40 to 32.1 percent. Meanwhile, the number of people receiving only meds had increased from 44.1 to 57.4 percent. Even the average number of therapy visits per patient per year had declined, from 9.7 to 7.9 percent. So far, in the succeeding years, there’s been no indication of any uptick; most likely, the numbers have continued to drop.

You might think this trend represents people’s preferences for the quick fix of a pill, rather than a slog through talk therapy, but you’d be wrong: surveys have consistently shown that depressed and/or anxious people and their families would rather talk to a real, live, human therapist than fill a prescription. In the June 2013 issue of the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, researchers reviewed 34 studies of mental health treatment preferences (patients and nonpatients) for anxiety and depression and found that people were three times as likely to favor psychological treatment (aka, psychotherapy) over medications. As the authors of the study drily noted, the fact that psychotherapy is declining and medications are far more prevalent implies “that many patients are not engaged in their preferred psychological treatment.”

Why not? Are they being talked out of it because a biomedical approach has been proven superior to pokey old talk therapy? Not at all. Psychotherapy isn’t only the treatment preferred by clients, it’s probably the best option, particularly for the commonest complaints, like anxiety and depression. Research shows not only that several major approaches—including cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT); acceptance and commitment therapy; interpersonal, family, and even short-term psychodynamic therapy—are successful stand-alone treatments for depression, anxiety, substance abuse, and other conditions, but that therapy significantly boosts outcomes for clients already taking meds for severe mental illnesses, including bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Furthermore, therapy appears to provide longer-lasting effects than meds and at lower cost over time (particularly given the vast sums involved in developing drugs), but without the side effects or withdrawal symptoms and relapses associated with going off them.

In fact, the much-vaunted psychotropic revolution seems to have fizzled. Not only does current research suggest that antidepressants work little better than placebo for mild to moderate depression, but medications are often massively overprescribed and widely misprescribed (antipsychotics for anxiety disorders, for example) when milder drugs don’t work. Even the drug companies seem tired: their sales are down, the patents on their great old moneymakers are quickly expiring, and they’re just about out of ideas, with no fabulous new blockbusters in sight.

So in what appears to be the twilight of the psychopharm gods, why aren’t therapy practitioners rising up, throwing off their chains, and reconquering lost mental health territory, not to mention restoring their once-respectable, middle-class incomes? In May 2013, the Clinical Psychology Review devoted an entire issue to the apparent demise of the therapy profession—why it’s happening and what might be done to rescue it. The main culprit, write the editors of the issue, Brown University psychiatrist-professors Brandon Gaudiano and Ivan Miller, is the pervasive medicalization of mental health treatment and the widespread belief that almost all forms of psychological distress are medical/biological problemswith medical/biological solutions. And if those solutions haven’t yet been found, they will be, any day now, with the next laboratory breakthrough.

This therapy-unfriendly worldview, amounting almost to a form of popular brainwashing, is sustained by the usual suspects: DSM, which provides a faux legitimacy to artificially constructed psychomedical disorders; Big Pharma’s financial, social, and political clout, which vastly outclasses Little Psychotherapy on every measure; direct-to-consumer ads for psychotropic drugs, which turn every TV watcher or magazine reader into his or her own personal psychiatrist; and decreasing insurance reimbursement for therapy, as well as increasing reimbursements for prescriptions, which means that if people want therapy, they’ll probably have to pony up for it themselves.

But Gaudiano and Miller also argue, not entirely convincingly, that psychotherapists are themselves at least partly to blame for their failure to hold their own against the biomedical juggernaut. Why? Because unlike the psychopharm industry, which sells its products on the basis of supposed scientific support (much challenged these days, by the way), therapists by and large don’t really like science, don’t believe it’s particularly relevant to their work, and in fact, often seem to regard research and therapy as antagonistic entities—as if you can be a good therapist or a good scientist, but not both. Most therapists appear to find the numerous treatment protocols available for empirically supported treatments, complete with step-by-step instructions and sample dialogue, irrelevant, if not downright repellent. Forty-seven percent of clinicians never use the guidelines, or “manuals” (a term that does suggest car-repair instructions), and only six percent claim to use them often. The rest, we can imagine, occasionally study them, say, to pass an exam, and then breathe a sigh of relief and never look at them again. According to a 2009 survey, 76 percent of social workers had used at least one “novel unsupported therapy”—the polite term by which psychotherapy researchers mean “pure bunk.”

In short, therapists stubbornly persist in clinging to intuition and personal experience as their guiding lights, and ignoring research showing that statistics trump individual clinical judgment. Even worse, these self-willed do-it-yourselfers use the much-ballyhooed meta-analyses showing that all credible therapies produce roughly equivalent results in order to do any damn-fool thing they want—which might include totally unsupported, useless, or even harmful methods. All this seems to suggest that most therapists are just too loosey-goosey about their practice for their clients’ or their own good.

Well, maybe. But this doesn’t explain why all those people who apparently prefer therapy aren’t getting it. Are they simply being steered away by primary care docs? Cowed by the constant barrage of pro-drug propaganda into believing meds are the only way to go? The authors don’t really say, except to suggest, as Gaudiano did in a New York Times op-ed in September 2013, that therapists’ indifference to evidence-based treatments creates an “image problem” for them among primary care physicians, insurers, policymakers, therapists themselves, and even the general public, which doesn’t realize how much research stands behind the “good” (i.e., evidence-based) therapies. Gaudiano and Miller suggest that unless therapists and their own lobbying organizations get with the program and insist that the profession become more “scientific” (more like the drug industry), therapists will continue to lose out in the popularity sweepstakes.

But barring the odd idea that the public is turning away from therapy because so many practitioners don’t hew to empirically validated methods (do people seeking mental health treatment really pore over academic manuals to learn which methods have the highest evidence-based ratings?), is it appropriate to make such a fetish of science in the field of psychotherapy? As Gaudiano himself suggests, psychotherapy rises from roots different from those of biomedical interventions and is perhaps not always or necessarily amenable to blinded, placebo-controlled research. Therapy’s advances don’t happen in the lab, but tend to come from “humble beginnings, born from an initial insight in the consulting office or a research finding that is quietly tested and refined in larger studies.” In other words, a therapeutic innovation usually emerges during the course of private conversations between people in a session, mediated by the (horrors!) personal intuition of a therapist, who’s noticed that the old standard operating procedures aren’t operating well.

Therapeutic practitioners and practices show far more divergence than is dreamt of in the philosophies of biomedical researchers. Therapists are social workers, pastoral counselors, PhD psychologists, medical doctors, school and prison counselors, business coaches, personal coaches, and even—still—psychoanalysts! They practice not only CBT, psychodynamic, interpersonal, existential, family, and couples therapy—and often two or three or more, all jumbled up together as the situation and the person seem to warrant—but also play therapy, dance therapy, music therapy, art therapy, drama therapy, child therapy, body therapy, mindfulness therapy, body-mind therapy, nature therapy, animal-assisted psychotherapy, and probably carpentry therapy (sounds like a good idea, actually).

You may claim that until these therapies can demonstrate their worthiness for an official pedigree among the empirically supported treatments, they ought to be legally forbidden the use of the sacred name of therapy. But don’t all these approaches resonate with one or another or several of the almost infinite range of human personality and imagination, suffering and need, life circumstances and requirements for healing? Is it inconceivable that they help many troubled and unhappy people who wouldn’t much like a course of CBT (many people, recall, actually don’t like CBT, scientifically worthy though it may be).

We have more than enough room to wonder whether psychotherapy can or should ever be completely “scientificized” in a me-too attempt to beat psychopharm at its own game. Neither the great pharmaceutical revolution, nor the proliferation of empirically validated methods, has reduced the prevalence and costs of mental disorders. Given the diagnostic creep in the DSM and the increasing use of psychotropic drugs, many more of us may be diagnosably crazy than we would’ve been before mental health treatment became so seemingly scientific.

Another reason for the low fortunes of psychotherapy is the lousy job therapists do of selling themselves and what they offer. Not only are they still unsuccessful at marketing their individual selves to the world, but their representative organizations have mounted a weak to nonexistent campaign in defense of what they do. This was begun, in a small way, by the American Psychological Association (APA), which has been running sweet, but not exactly powerful, animated cartoon videos—little tube people explaining to their unhappy friends why therapy might help—all under the general heading “Psychotherapy Works.”

In the meantime, besides the problem of shoring up psychotherapy’s wobbling scientific credentials (it never had many to begin with) or expanding the market for it, there’s the little matter—as old as the field itself—of coherently defining what psychotherapy is. Is it a quasi-medical intervention for a quasi-disease entity? A form of benign reparenting? A special kind of friendship? A course in deep psychological self-excavation? A kind of behavioral education? A class in corrective thinking? Philosophical training? Crisis management? Spiritual enlightenment? Some observers have suggested that many therapists ought to drop any medical pretensions at all, eschew the expectation of insurance reimbursement, and admit to being what they are: personal life consultants for hire. Others, like former APA president, chief of mental health at Kaiser Permanente, and professional soothsayer Nicholas Cummings, argue that medical and mental healthcare can’t really be separated, and that psychologists, as “behavioral healthcare” experts, ought to be routinely embedded in the medical staffs of large healthcare organizations. Cummings predicted in the July/August 2001 issue of this magazine that the future of therapy belonged largely to short-term group psychoeducational models, with only about 25 percent of therapy being individual. While that ancient prediction doesn’t seem to have been borne out quite yet, certainly it does seem in line with the ever-more-stringent emphasis on cost effectiveness in therapy—and the most empirically supported of all empirically supported therapies, CBT, is nothing if not a vast, multifaceted psychoeducational movement.

And then, finally, it’s often said that millions of millennials get all their mental health needs met via their digital devices—through tweets, blogs, psychology sites, chatrooms, videos, Facebook, and the like—and simply aren’t interested in the kind of slow-talk interaction most elderly therapists (average age 50 to 56) provide, no matter how evidence-based the approach. This seems dubious, to say the least. Never before have young adults been so free to do what they want, but never before has it been so hard for them to find their place in the world, in the face of unprecedented challenges and pressures—economic, relational, sexual, personal—that leave many paralyzed, unable to move forward. Most of the rules, habits, norms, standards, and expectations that were usual for young people even 20 years ago have now vanished, leaving for them a yawning void in the social fabric.

True, most of these young people wouldn’t appreciate the clichéd clinical style that was once de rigueur among therapists (“And, how did that make you feel, hmmm?”). But as much as any generation in history, they need and want guidance, a helpful conversation, and a genuine connection with a mature, wiser adult—somebody who can listen to them with kindly intelligence, fully grasp the nature of their dilemma, and help them discover within themselves what they need to make their way in the world. This, ladies and gentlemen, is the job of a good therapist!

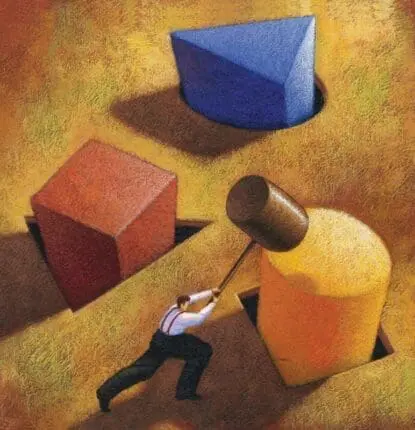

Illustration © Illustration Source / Paul Vismara

Mary Sykes Wylie

Mary Sykes Wylie, PhD, is a former senior editor of the Psychotherapy Networker.