In the late 1970s, I was a Black kid from Philadelphia enrolled in the family therapy graduate program at Florida State, an institution that had graduated its first Black grad student only in the mid-’60s. I was the only Black student in the program, and there were no Black faculty. Issues of race as a factor in people’s lives rarely came up in class. If I brought it up with my supervisors, they responded, “If you want to be a good clinician, just learn the rudiments of family therapy and then apply them to whatever family you see. Don’t make race a special issue.” The entire emphasis was about generalized treatment methods without paying attention to race, class, or gender issues.

Then, through the early ’80s, the feminist critique began to expose the rampant gender-based inequities and sexism inherent in the field and the way family therapy perpetuated mother-blaming in its explanation of family interactional patterns. It made what had been previously invisible impossible to ignore. Nevertheless, largely advanced by white women, it didn’t directly address issues of racial inequality and racism, even though by pointing out how family therapy privileged males, it also exposed the privilege enjoyed by white people. Just like women, people of color were marginalized. Seeing how the field’s feminist leaders pushed boundaries and withstood the firestorm of criticism they received from the influential men in the field was both inspiring and a little frightening for therapists of color. I remember thinking that if whites could so viciously attack each other over their differences about gender issues, what would happen to people of color who dared talk openly about race and racism.

One moment at an American Association of Marriage and Family Therapists (AAMFT) national conference in 1984 stands out for me as especially powerful. Feminist therapist Marianne Walters, in her keynote address, called attention to both the issues of sexism and racism by flashing on a big screen the pictures of all the keynote speakers and members of the AAMFT board of directors. She began by saying that she wanted to pay homage to the thinkers and shapers of the field, and then one by one, she thanked them by name. As images of one white male after another loomed over the ballroom, the extent of the overwhelming gender imbalance among leadership roles became more and more apparent. So albeit in a somewhat indirect way, the feminist critique drew attention to racial privilege as well.

During this period, there were certain books that succeeded in raising consciousness about social issues within the field. Although Monica McGoldrick’s groundbreaking Ethnicity and Family Therapy didn’t deal with race specifically, it succeeded in adding ethnicity and culture to the list of contextual factors that should be considered when working with families. Unlike the feminist critique, the topic of ethnicity was easy for everyone to discuss, because it didn’t call attention to structural inequities, power, and privilege. Even more importantly, Nancy Boyd-Franklin’s book Black Families in Therapy marked a crucial milestone for the field by focusing on the special challenges Black families face in a racist society. And it was practical to boot, providing tips and tools for effectively engaging and treating Black families.

Nevertheless, it was still hard to get material about race into academic journals because reviewers found it too inflammatory. I remember conference organizers discouraging me from focusing directly on race in my talks and strongly encouraging me to instead use the less threatening term multiculturalism. After all, the major power brokers of the field at the time were white. For people of color, forcing a conversation about race seemed like committing professional suicide. So some of us took a more strategic approach. I remember publishing a paper called “The Theoretical Myth of Sameness: A Critical Issue in Family Therapy Treatment and Training” as a safe way to examine the potentially explosive issue of race in a more general discussion about “sameness and difference.” I was opening a door without sounding too confrontational.

One year, in the climate of the times, I offered a session called “Breaking the Silence” that gave voice to the sense of stifling frustration, deep disappointment, and race-related pain that many people of color felt unable to openly express to their white colleagues. For people in the minority community, it was as close to an open act of defiance as many of us had come: no more walking on eggshells regarding issues of race, no more apologies for acknowledging when and how we saw racism in the field. For my own part, I’d learned a lesson or two from my feminist friends about the courage it took to be outspoken about “divisive issues,” and the importance of taking good care of yourself in the face of the inevitable pushback that comes from pointing out differences in power and privilege.

Throughout the ’90s, my process of becoming more transparent about the struggles of being a Black therapist in the field continued. I published an article in the Networker called “War of the Worlds,” in which I talked openly for the first time about the compromises people of color in the field have to make to be deemed acceptable by their white counterparts. To date, nothing I’ve written for the Networker, or any other publication, has generated more personal letters—strongly supportive as well as scathingly critical—than this one. Then in 1996, I gave a keynote at the Networker Symposium. It was the first time that a nonwhite clinician had delivered a major plenary address at a national family therapy meeting of such a size.

Pleased as I was to receive the invitation, I also felt the tremendous burden of responsibility as I began my talk extemporaneously by describing all the voices of Black people for whom I felt I was a representative. It was a very emotional experience for me. Designed to engage the broadest possible audience, my theme was the sense of “psychological homelessness” that so many people of color struggle with as they try to fit into different, mutually exclusive worlds, leaving them without a safe place, a true home. Women, LGBTQ folks, immigrants, estranged daughters and sons, and emotionally cut-off parents could all relate to what I was saying.

Thankfully, by the late ’90s, an increasing number of training programs began developing curricula that specifically addressed issues of race and social justice. But while there’s been a positive shift in our awareness of race, the discomfort and awkwardness in addressing it is still prevalent. Regardless of the venue or the participants, conversations about race are difficult to facilitate. People of color fear being judged as race-obsessed, angry, and hypersensitive. And whites often fear being misunderstood, perceived as a racist, or saying something that will trigger the anger of people of color. For the most part, a fundamental attitude of mutual mistrust underlies discussions of race between Blacks and whites, making meaningful interactions across the great divide of race hard to achieve. It takes both will and skill to address the issue of race, and even though the will has generally increased, the skill is still lagging behind.

Over the years that I’ve been facilitating these kinds of interactions, I’ve realized that the most successful ones must start with the soul work of seeing, being, and doing. Seeing is about our increasing ability to recognize how much the color of our skin defines our day-to-day experience. The next step is being able to engage in a process of self-awareness about what it means to be white or a person of color and what role we choose to play in addressing the racial inequities we see around us. The final step is, of course, the most difficult—to actively engage in doing something about them.

If ever there were a critical moment for constructive and courageous conversations about race, power, and privilege in our practices, communities, and the broader society, this is it. Personally, I feel affirmed in the credo that whatever our training or orientation, our work as clinicians should ultimately be devoted to healing the world, even if it means addressing that huge task in 50-minute intervals at a time.

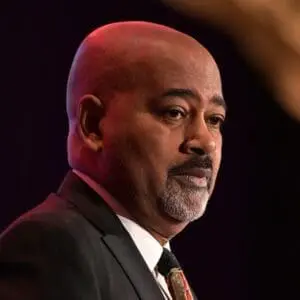

Kenneth V. Hardy

Kenneth V. Hardy, PhD, is President of the Eikenberg Academy for Social Justice and Clinical and Organizational Consultant for the Eikenberg Institute for Relationships in NYC, as well as a former Professor of Family Therapy at both Syracuse University, NY, and Drexel University, PA. He’s also the author of Racial Trauma: Clinical Strategies and Techniques for Healing Invisible Wounds, and The Enduring, Invisible, and Ubiquitous Centrality of Whiteness, and editor of On Becoming a Racially Sensitive Therapist: Race and Clinical Practice.