Revisiting “Soul Work,” a piece I wrote almost 20 years ago under Rich Simon’s editorial guidance, was a poignant reminder of what I’ll miss so much about him as a dear friend and colleague. Rich was always willing to push the envelope when it came to important issues. Well before the Black Lives Matter movement—before it was acceptable to talk publicly about the hostility and racism many police departments inflict on communities of color and Black people in particular—he championed this story about a violent encounter I had with the police.

I vividly remember the process of writing this article. Not once did Rich ever ask me to tone down my message about racial injustice—something that, over the course of my career, I’ve often been asked to do by white people in positions of power. For them, my authentic Black voice was always considered too angry, too polarizing, too divisive: in other words, not white enough. Like many people of color, I’d mastered the skill of talking to white people in carefully worded codes that appealed to their fragility, accommodated their discomfort with honest conversations about race, and betrayed my integrity.

But Rich was different. When he was obviously uneasy with something I said or wrote, especially when it challenged his whiteness, he became more curious. He leaned in! And we had honest heart-to-heart conversations as a result. Over many years, and many conversations about our shared obsession with basketball, our bond deepened, crossing a racial divide in a way that’s all too rare in our society. We didn’t always agree on things, but I always felt genuine respect for him as friend, as well as a demanding and passionately engaged editor. Rich was witty, cynical, engaging, brilliant, and committed to making a change in the world, in his unique way.

Writing this article, one of many I worked on with Rich, was more than just another assignment. It was an opportunity to share my story about a humiliating injustice that, at the time, I’d never spoken about publicly. Somehow, Rich intuited that it was also an opportunity to heal. At some point, after the fifth or sixth draft, he said to me, “Kenny, you say in the title that this is your ‘soul work,’ but where is your soul? I don’t feel it in your words. You’re still standing on the sidelines. I need you to get in there!”

I heard him, but I didn’t believe him. I didn’t think he actually wanted the uncensored truth of what it means to be a Black man in a white world. I even wondered if this was some strange, modern-day version of blacksploitation. But it turned out that Rich was a companion of getting to the truth, even if it made him uncomfortable. He welcomed the intensity. In fact, under Rich’s guidance, the Networker provided me with an important platform—in print and on the Symposium stage—to engage our field in a discussion about the topics that mattered to me and others like me.

Rich, I could consult every dictionary on Earth, but I doubt I’ll ever find the words to adequately describe how much you meant to me. And I hope you can feel my soul in this, buddy!

P.S., I don’t know if you get ESPN up there, but the first game of the new NBA season is tonight, and I’ll be thinking about you!

From the archive: September/October 2001

As I maneuvered my nearly new Yamaha 440 motorcycle through the oil-slicked, potholed city streets, I had only one thing on my mind: watching the Lakers hammer the Sixers. On that early November evening in 1982, I was on my way to my parents’ home to watch the game, and I was—still am—the kind of basketball fan who has to be there for tip-off. In my haste, I glided my motorcycle to an incomplete stop at a corner, revved up again, then noticed, with a sinking heart, an ominous flash of red in my rearview mirror.

“License!” barked the ruddy-faced policeman who had motioned me over. I produced it quickly; I knew I had rushed through that stop. Just give me a ticket, I thought impatiently, so I can make tip-off. As the cop studied my license, I covertly looked him over. He was a stockily built, sandy-haired guy in his late 30s, with a kind of alert, coiled quality about him. “Says here you’re supposed to be wearing glasses,” he stated in an accusatory fashion, cocking his head as though to get a better look at me. “I don’t see ‘em.”

“I’m wearing contacts, sir,” I replied.

“Yeah?” he countered disbelievingly, shining his flashlight within a few inches of my eye. “You’re going to have to pop one out and show me.”

I took a deep breath. “That would be difficult, sir,” I said, “because my hands are filthy right now. If I were to take it out now, I wouldn’t be able to put it back in.”

“Take the goddamn contact out,” he spit out. His voice was low and tight, and his face had turned a shade redder. I felt rage rising in me, fighting with fear. I was 29 years old and had never before spoken a single word to a cop under these circumstances, because I well understood the risks of antagonizing a policeman. Shaking with anxiety and anger, I removed one of my lenses, hoping against hope that if I just kept my cool and didn’t aggravate this guy too much, I could soon be on my way.

He nodded dismissively at the tiny, transparent disk on my palm, as though it was now too trivial a matter to bother with. “Where’s your owner’s card?” he snapped. My heart tightened. When I’d left my home earlier in the day, I’d been in a hurry and had forgotten to take it out of the glove compartment of my car. When I told him this, his lip curled in derision. “That’s a good one,” he said. “Nice try, boy.”

He leaned into his car and murmured something unintelligible into his radio. Within minutes, a tow truck appeared. After talking privately with the tow truck driver, the cop turned to me. “Put the bike on the truck, boy,” he ordered. “We’ll see who owns that cycle.” As I stood motionless in disbelief, his voice grew louder and more menacing. “Do you hear me, boy? I said put the fuckin’ bike on the truck!”

This was too much—I felt my dignity being murdered right there on the street. In an attempt to cling to some small piece of self-worth, I responded, “You know my name, sir. It’s right there on my driver’s license. Until you call me by my name, I’m not answering you.”

He laughed; it sounded more like a bark. “That a fact, boy?” Now he began poking me in the nose with his finger, a series of hard, angry stabs that made my eyes water with pain and my nose bleed. As a small crowd began to gather on the corner, mostly African Americans from the surrounding neighborhood, he muttered a few more words into his radio and suddenly lights were flashing everywhere, tires screeched, and four or five more policemen jumped out of patrol cars.

“Now, you’re gonna behave, boy,” the cop smirked at me. He was still jabbing me in the face; my nose was bleeding profusely now. I saw an older woman in the crowd shaking her head as she fought back fury, fear, and powerlessness. “Why do these policemen have to be so nasty?” she asked no one in particular.

Something snapped inside me. “I understand why, ma’am,” I answered, my voice full and clear. “You see, they find these fragile guys, give them a badge and a gun, and, suddenly, they become Superman overnight.”

For a moment, there was perfect silence on that street corner. The cop was staring at me; I saw that he was breathing hard. “I get it,” he finally said with a tight, crooked smile. “You’re one of those smart-ass niggers.”

Grabbing me by the neck, he threw me down on the hood of his patrol car and cuffed my hands behind my back. Suddenly, he and another cop were beating me with nightsticks, raining blows across my neck, my back, the backs of my thighs. When I felt the first, hard whack across my flesh, I hoped, against all reason, that a few blows might satisfy them, but their clubs continued to crash against my body, again and again and again. Dimly, I heard the sounds of men above me, laughing. I thought I was going to die.

Lessons in Survival

I didn’t die on that street corner that night. I could have—a careless, or purposeful, blow to the head would’ve taken care of that. Instead, bloody and nearly unconscious, I was shoved into a patrol car, arrested, fingerprinted, and thrown into jail for the night. The charges filed against me included disorderly conduct, disturbing the peace, and, more seriously, “making terroristic threats against a police officer.” If convicted of the last charge, I’d go to prison.

The next year and a half was a waking nightmare. As I waited for my case to come to trial, I was working as deputy executive director of the American Association of Marriage and Family Therapy, with a part-time private practice on the side. To my colleagues and clients, I was a middle-class Black man with a thriving professional career and a polished, confident demeanor. They didn’t know the other me—the guy who’d come home to his apartment and bury his face in his hands, consumed with anxiety over the possibility that, a year from now, he might be a caged animal.

I’d talked with friends who’d done time, so I knew what awaited me. The confinement, the filth, the violence. Especially the violence. I wasn’t a tough guy; I’d never been in a fight in my life. How would I come out alive? Nights were worse: I had trouble falling asleep and when I finally did, I often woke up screaming, caught in nightmares of courtrooms and grim-faced judges and silent men on either side of me, ushering me away.

My father had a solution. “Plea bargain, Kenny,” he advised me. Admit to something, whatever was necessary to reduce my sentence from jail time to probation. I understood his impulse. My dad had grown up in the Deep South where many Black men were, as the late Billie Holiday put it, the “strange fruit” hanging from southern trees for doing far less than I had done. From my earliest boyhood, he’d counseled me to do exactly what he’d done to keep himself safe and alive. Don’t do things to threaten white people, Kenny. Don’t stop and look too hard at that Mercedes parked on the street. Keep moving. Blend in. Muffle your voice. Survive, Kenny.

Survive.

And now, at this moment when I had more at stake than ever before in my life, my father begged me to plea bargain. I saw the worry in his eyes; I saw how desperately he wanted me, his beloved firstborn son, to stay safe. “You’re naive if you think you’ll get a fair trial, son. If you plead not guilty, you’ll lose. And then they’ll do whatever they want with you.”

I listened to my dad. I’d spent my life up to then, in fact, listening to, and heeding, his advice. I’d fashioned a life of caution and prudence, a life dedicated to making myself inconspicuous, to offending no one. If I witnessed an injustice, I rationalized it: It hadn’t been that bad. If someone disrespected me, I swallowed my anger and let it go. In the careful world I’d constructed for myself, a plea bargain made perfect sense: Why risk jail when I could simply admit I’d been wrong and walk?

But then I would see the cop standing over me all over again, feel once more his finger pummeling my nose, his blows on my back. Even more painful, I felt again the utter humiliation and powerlessness I’d experienced on that street corner, when nothing I did, or could do, made any difference, when all the polite deference that my father had counseled had counted for nothing, when my entire personhood had been canceled out. That cop had some ideas about me and they were all that mattered. Now, you’re gonna behave, boy. I knew I couldn’t bear to be that invisible, that degraded, that voiceless ever again.

I pleaded not guilty.

The Anatomy of Silence

Throughout the long, harrowing pretrial period, I managed to continue my small therapy practice in Washington, DC. Up to then, my clinical work had reflected a fairly conventional blend of psychodynamic and systems thinking. First, I’d look at my clients’ suffering through an intrapsychic lens—what was happening within each person to make him or her unhappy? Next, I’d look at patterns within the family for sources of distress. These were the boundaries of my therapeutic territory: I was convinced that all problems and all solutions resided within the mind and within the family.

But now, this approach felt thin. Limited, somehow. Even in the midst of my obsessive worry about my upcoming trial, I felt the first stirrings of a different, more encompassing way of looking at my clients’ challenges. Not long after my encounter with the cop, I began to work with a Hispanic couple who seemed consumed by bitterness toward each other. The man, Pedro, who worked for a landscaping company, swung between extremes of furious verbal abuse toward his wife and silent, glum withdrawal. In turn, his wife, Rosa, a school librarian, criticized him in subtle ways about his intelligence and about the lack of prestige that characterized his job.

On a hunch, I asked Pedro, who was the only Hispanic man at his company, to describe his relationship with his supervisor. It turned out that his boss had consistently patronized him and discouraged him from taking any initiative, telling Pedro outright at one point, “My job is to have ideas, your job is to haul fertilizer.” Spontaneously, I found myself responding to Pedro by introducing the idea of race- and class-based prejudice, and the connections between the crushing of a soul by the broader society and a faltering relationship at home.

It was the first time I’d ever brought the reality of social injustice into the therapy room; I surprised myself. But it felt right and true—truer than anything I’d ever done. Feeling our way, Rosa, Pedro, and I began to work together at the intersection of mind, family, and society. As I helped them better understand their inner worlds and the dynamics of their relationship, I also explored with Pedro how he could reclaim his voice at work—by speaking up to his boss on his own behalf in a calm, effective way. Bit by bit, Pedro’s recovery of his voice on the job began to give him the emotional room to be more vulnerable and loving in his marriage.

Voice and voicelessness. I found myself becoming more and more curious about these concepts. My experience on that now blood-stained street corner was pushing me to explore the ways that society robs so many of us of our voices. Being stripped of my own voice that night helped me become mindful of the ways we get stunted and warped when we’ve been silenced. Whether my client was a woman living with an abusive husband, or a gay person living in a homophobic society, or a kid overwhelmed by cruel peers, I began to explore with them the anatomy of silence—what it felt like to be voiceless, who benefitted from their silence, and what they could do to recover their voices and themselves.

Making the Whole Visible

My trial was mercifully short—just two and a half days. Still, at the moment that the jury filed back into the courtroom and the foreman rose to address the judge, I think I stopped breathing. I couldn’t help but notice the worried, exhausted look on my mother’s face as her eyes filled suddenly with tears.

“Not guilty.” On all counts.

I walked out of the courtroom a free man. But the man who got his life back that day was not the same guy who rode his Yamaha through the city streets that chilly November night, intent on watching a Sixers-Lakers game. I felt in myself a growing desire to work with the larger social forces—racism, sexism, homophobia, poverty—that silence and dehumanize so many. For I was one of the lucky ones. I was able to walk away from my encounter with the legal system because I was economically privileged. I could afford two private attorneys who shaped the kinds of arguments that allowed my innocence to become clear to a jury. For the many African Americans who collide with cops on the streets, the outcome is often jail or, worse yet, death.

If I had been poor, I would have gone to jail. I know that.

Not long ago, a university colleague of mine remarked to me about his therapy work: “My job is to work with everyday people trying to resolve everyday problems.” Prior to my experience with the cop, I’d have readily agreed with him. Now, I couldn’t disagree more vehemently.

I believe that therapy is about daring to go where it hurts and trying to transform not only what hurts, but also the larger conditions of separateness, hate, and misunderstanding that contribute to that hurting. I’ve been told many times that it’s not my mandate, or that of any therapist, to try to transform the human condition. My job, I’ve been reminded, is to help specific couples and families enjoy better relationships.

But I don’t believe that relationships can thrive when pressed against a backdrop of oppression or voicelessness. Everything is connected: social prejudice and fractured relationships, psychology and ecology, domination and subjugation. On my good days, I can even feel the connection between my encounter with the policeman and his own experience of powerlessness, somewhere, someplace.

My task, as I now see it, is to stitch these fragments back together, make the whole visible again. One family, one room, one hour at a time. I suppose I could say that the work I do now to promote healing at the juncture of personal and social pain is my “preferred approach” to therapy. But it’s about so much more than an approach or a preference. It’s about how we live our lives and, in doing so, create space for one another. It’s about soul work, my soul work.

Reprinted from the September/October 2001 issue of Psychotherapy Networker.

Illustration © Illustrationsource.com/Stephanie Carter

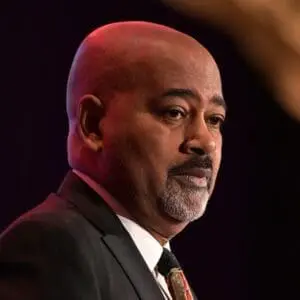

Kenneth V. Hardy

Kenneth V. Hardy, PhD, is President of the Eikenberg Academy for Social Justice and Clinical and Organizational Consultant for the Eikenberg Institute for Relationships in NYC, as well as a former Professor of Family Therapy at both Syracuse University, NY, and Drexel University, PA. He’s also the author of Racial Trauma: Clinical Strategies and Techniques for Healing Invisible Wounds, and The Enduring, Invisible, and Ubiquitous Centrality of Whiteness, and editor of On Becoming a Racially Sensitive Therapist: Race and Clinical Practice.