The term midlife crisis is now in its 50s. It was coined by Elliot Jacques, a psychologist in the 1960s, who found that depression and elevated rates of suicidality often accompanied the passage into midlife. It didn’t take long for the concept to be embraced by a public convinced that graying hair, ebbing health, and long-held dreams dashed by the march of time could sour an aging person’s life, and bring on reckless and self-destructive behavior.

But more recent research has challenged the idea. The National Institute of Aging says only a third of Americans over 50 report having a crisis in midlife. For those who do experience an initial life-satisfaction decline, investigators have found evidence of a U-curve, meaning that they often rebound toward the end of the middle years. After all, now that we can stay sharp and often sexually active into our 80s, midlife no longer heralds the end of physical and mental vitality.

But if midlife isn’t inherently troubling, how should we therapists think about it?

While many clients do wrestle with feelings of loss and behavior changes at this stage, many others awaken to a greater awareness of emotion, a more liberated attitude toward sex, and a passion for new experience.

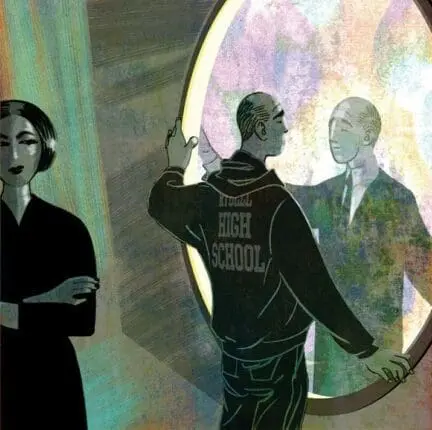

Therefore, rather than thinking of midlife as an emotional unraveling, I believe it’s more helpful to reframe this stage of life in our early 50s and 60s as “second adolescence,” a time when we’re old enough to appreciate how short life is, but young enough to find new ways to enjoy it. Instead of a time of existential pain, it resembles a liberating assertion of selfhood, and a chance to explore new identities. Though often tumultuous, it can be a growth opportunity. And not unlike the teenage years, it can bring up complicated life choices, but with our help, clients can gain a fuller sense of purpose and a positive self-definition to guide them through life’s later stages.

The Retiring Rebel

Take Jack, 64, and Marion, 59, who sought me out after 20 years of marriage. For most of their married life, they’d had a loving, committed relationship, with Jack working at a lucrative corporate job and Mary working part-time at a nonprofit clinic while raising their well-behaved and responsible kids. But now, after decades of fidelity, Jack was expressing interest in other women, drinking hard with buddies, and taking hallucinogens at parties.

After quick introductions in our first meeting, I asked Jack and Mary to face each other and explain what had brought them each to therapy. Marion turned her head toward Jack but leaned her body away, arms crossed, and announced, “I want out of this marriage.”

She went on to say that while she thought Jack was having a midlife crisis, she’d never seen one like his. “Maybe if you were depressed, I could muster some compassion for you. But you just don’t seem to care about anyone but yourself. Threatening to cheat? Doing drugs and staying out all night? And you expect me to put up with this? Who are you? I don’t even recognize you anymore.”

I thanked Marion for her honesty and turned to Jack, who was gazing numbly at the ceiling. “Why have you come here today, Jack?” I asked.

Jack tried looking at Marion, who glared at him in return. He sighed and said he didn’t want to break up the marriage, but felt restless and bored with their life, particularly their sex life. “We could stay together and still make things better if you’d agree to open our marriage,” he said.

When Marion rolled her eyes in my direction, he turned to me to make his case. “I know progressive people our age who explore alternative relationships. I’d like us to hit the clubs with them.”

Marion let out a bitter laugh and I stepped in, noting, “Jack, you seem to be set on living a life right now that’s strictly on your own terms. It’s as if you’re rebelling against your marriage.” It seemed that Jack was projecting a parental role onto Marion, asking permission to have more fun, and then resenting her when she wouldn’t agree to a more adventurous sex life.

Jack turned to Marion and said, “I want to live my life. I don’t want you to tell me what to do anymore. I want to explore more before I die.” His search for separation and individuation are classic indicators of a second adolescence. In his case, the underlying reasons were clear. His body wasn’t what it used to be, he worried he couldn’t perform sexually much longer, retirement was near, and his identity was no longer wrapped up in kids and work.

Jack and Marion were in a tenuous place, and I took Marion’s threat of divorce seriously. Research shows that couples their age divorce at twice the rate they did 20 years ago. I decided to end the session by telling them they were facing a crisis of mutual understanding and needed to have some honest conversations about their sex life and what each of them wanted from it. I also underlined that they were in a confrontation with time that was spurring Jack’s behavior and sense of urgency about making changes in his life.

Both of them nodded at this idea. I added that Jack might be in the throes of what they might think of as a second adolescence, meaning Jack’s self-interested search for new experiences parallels in some ways what many people experience in their teen years. I explained that with the help of therapy, they might both come out the other side of it stronger and more content as a couple. While Jack sat there quietly, Marion, lips pursed, looked from me to Jack and back again. I could see her worrying that I was somehow excusing his behavior.

When I asked Marion how she was reacting to what I was saying, she responded, “It may be an idea that makes some sense,” she said. “But what am I supposed to do with new this label? It doesn’t make me like who he is right now any better.”

After assuring Marion that I wasn’t endorsing Jack’s new path or ignoring her objections, I said, “I’d like you to explore what kinds of experiences you both miss now that you’re in midlife.” I wanted them to see the broader picture and seriously consider what each of them might like to have in their lives now.

When we next met, Marion acknowledged that she too desired change. With their children gone, she realized how much she was swept up in nostalgia for her own youth. In fact, she’d started googling Led Zeppelin, Pink Floyd, and Steely Dan, and getting lost in memories of dancing in the crowds at their shows. We talked about the pleasures of letting loose and how that freedom so often evaporates with age.

I then encouraged her to switch gears and tell me what wasn’t great about her teen years. I wanted to know what experiences she might have missed out on in her youth, and not focus solely on Jack’s restless midlife searching.

“Well,” she said. “I hated the social pressures, and I never really fit in.”

“A valid and common experience,” I assured her. I asked if Jack’s behavior might be reminding her of this time. She talked about how untrustworthy teenagers can be and how Jack seemed childishly selfish in a similar way. She also resented being put in a position of nagging him. When I suggested it might be desexualizing to be put in such a parental role, she readily agreed.

Jack raised his eyebrows at this possibility, and we ended the session with a promise to discuss sex when we next met, especially how mechanical their erotic life had become. Grown-up sex, I wanted them to discover, could be more satisfying if they were willing to go beyond a rigid focus on intercourse and ejaculation.

New Age, New Self

I prepared for our third session by reminding myself that during midlife, a now-or-never rush toward pleasure after a lifetime of pursuing adult goals can often lead to infidelity or strained sexual relations. So when Jack walked in and announced he was done with threatening to cheat on Marion, I was pleasantly surprised. However, he added, he still wasn’t ready to settle for what he saw as the same old sex with her. “Clearly, you’d rather take care of matters yourself,” Marion retorted. Apparently, she’d walked into their study earlier that week to find Jack masturbating in front of the computer. He’d became incensed and accused her of spying on him—which she immediately denied. Still, he’d moped around for days afterward.

When I asked him about the incident, Jack said, without looking at Marion, “She was invading my space.”

Marion took a deep breath and said, “Jack, you really are acting like a child, and I already raised two of them. I’m not trying to control you. I don’t care if you look at porn. It’s your reaction when I walked in that’s the problem.”

Just as in first adolescence, people in second adolescence are testing roles and trying to deepen their sense of self. They often pull away from their spouses, creating conflict to feel their individuality. But completing a successful second adolescence with a spouse includes working on open communication and developing a vision not only for the future of their intimate relationship, but for healthy ways of establishing boundaries.

I asked Jack if he’d noticed that he was indeed parentifying Marion, treating her like a mother who’d walked in on a masturbating teen. “Did this sound right?”

“Well, as a matter of fact, my mom did walk in on me all the time. She was always. . . .” He trailed off. I asked him to see if he could make eye contact with Marion. He faced her and continued. “From when I was 10, I wasn’t allowed to close my door, not even at night.”

“Do you remember how that felt, Jack?” I asked him. Adolescence is often marked by feelings of shame, and I wondered if Jack could look underneath the presenting issue of his marriage to explore this high-intensity emotion.

“It felt intrusive,” he whispered.

Marion was moved by Jack’s confession, and turned to him to say, “You’ve become so withdrawn. You drink too much. I feel like I’m losing you. For me, that’s the real problem. I’m losing you.”

Marion started to cry and Jack teared up too. When I asked him why, he said, “I feel everything so intensely these days.”

I asked Marion to move closer to him and hold his hand. When she did, he told her, “I even cry at car commercials now. I don’t know what’s happening to me.”

I told him that many men his age experience a drop in testosterone, and find newly emotional, estrogen-fueled reactions can feel uncomfortable. For other men, this sensitivity can be a welcome change, a way of becoming involved in the world in a deeper way. Helping these men channel this new empathy and compassion gives them a second chance at understanding and managing difficult emotions.

As a therapist, my job is to help partners in second adolescence identify and voice their confusing emotions. Increasing their self-awareness can help assuage mood swings and encourage feelings of hope and growth. Helping them label their second adolescence as a normal developmental stage reduces some of their bewilderment and sense of shame.

At this time of role confusion, even professional success and fulfilling roles set out in earlier years can lead to its own frustrations. When everything we thought we were supposed to do in life is accomplished, we can feel lost and unsure about our next identity or our true self. That confusion can be accompanied by a renewed search for purpose and a heightened sense of urgency about the future.

Jack talked to Marion about it this way: “Things feel new now. I feel like a new person. I’m not sure what I should be doing. The old me just went to work, fed our kids, mowed the lawn. I did all the right things, but I lived my life without really feeling alive.”

Marion said, “But those roles made you happy. If you wanted other things, you should’ve told me.”

Jack shifted closer to Marion. “I didn’t want to feel like I was failing,” he responded.

Men are often most rewarded for the roles they play, not for who they are. These roles may bring temporary satisfaction, but by midlife they can feel empty. Many older men have compartmentalized their dreams, forgetting who they wanted to be before they were good parents or successful at their jobs.

“What did you like to do when you were a child?” I asked Jack.

He thought about it for a long, quiet moment. “I’d walk in the woods for hours. I loved nature.”

“It might be time to bring that back,” I suggested.

Jack agreed to start taking hikes without parentifying his wife by asking her permission beforehand. He decided to contact his local Sierra Club, feeling a new sense of purpose in protecting the earth, conscious of the consequences for future generations. Soon Jack was spending every Saturday morning staffing a booth near the entrance to the state park. He began inviting people he met through the volunteer program home for lunches, and he and Marion slowly made a new group of friends. We both encouraged Marion to engage her own passions and she somewhat reluctantly agreed to explore an expressive dance class in town, which ended up being a deeply joyful experience.

It was challenging at times, but I continued to work with Jack and Marion to reengage sexually in new ways that brought them both pleasure. One Saturday, Marion even set up the old family tent in the backyard, hiding it from Jack until the sun went down and then seducing him under the stars. Jack shared this story with one of the buddies he’d been drinking with months before. The buddy revealed his own impasse with his wife and Jack was able to give his friend hope that if they reconnected with honesty and each made some meaning in their lives, they too could both come out on the other side.

Second adolescence is a time to grow up—but not just by acting “mature,” which is often associated with letting go of recklessness or fun activities that seem selfish or don’t serve the family’s needs. The goal of second adolescence is to remind ourselves that creating a satisfying identity is just as important now as it was in our teenage years.

It’s a time to recognize that growing older doesn’t mean that we need to give up who we are and become less engaged in life. Instead, it’s a golden opportunity to recreate ourselves in meaningful ways, and even to resolve some of the challenges that the first adolescence may have left unsatisfied and incomplete.

Case Commentary

By Peter Fraenkel

Tammy Nelson writes about her work with the kind of couple I see frequently. Decades into marriage, with successful careers, financial security, and kids finally launched, one partner voices his or her desire to regain a lost sense of vitality. Usually, there’s been little sex or other forms of intimacy for years, and marriage has become a form of monkhood. As the one partner’s dissatisfaction gets more fully voiced, the other often feels shocked and betrayed. Yet with some exploration, it’s revealed that she or he, too, wants more than the relationship currently affords.

So both partners are longing for renewal, rejuvenation, expansion, and creativity, even if it’s only one partner initially voicing these desires. When, as in this case, it’s the man who’s complaining, I usually explore the ways that women have shouldered the greater burden of childcare, housework, and family management, even as they hold full-time jobs. I talk with them about how research has shown that a feeling about unfair division of family-based labor is highly correlated with a loss of sexual desire. I typically work with the couple to create regular times for pleasure, and I usually find that getting the husband to take over items on the couple’s to-do list often rapidly restores the female partner’s desire for intimacy. I’ve found that this approach engages both partners in committing to revitalize their connection.

Nelson—whose writing, workshops, and active, humorous approach to therapy I thoroughly enjoy—takes a different tack, one I have a problem with: labeling the man’s “rebellious” behavior a sign of a “second adolescence.” While she rightly notes that the old notion of a midlife crisis is pathologizing, and statistically infrequent, casting these longings for renewed vitality as signs of a second adolescence seems to me equally negative and, frankly, inaccurate. In fact, recent research suggests that most adolescents don’t go through the stark rebelliousness they’ve developed a reputation for.

It seems Nelson intends to honor the man’s desire to redefine his sense of self, move beyond accustomed but worn-out roles and responsibilities, and restore adventure and expanded possibility to his life. But rather than viewing the couple more systemically, and seeing Jack as the partner who’s likely speaking for both his and his wife’s desires for renewed passion, she casts his behavior as a teenage-like rebellion against Marion, suggesting that he’s put her in the role of his parent. Neither partner seemed to respond well when presented with this framework: Jack becomes silent, and Marion declares that this label doesn’t “make me like who he is right now any better.”

In this postmodern era of greater collaboration and transparency with clients, I’m always looking to highlight the positive sides of clients’ struggles, and to provide them descriptions of their behavior that compliment and even inspire them. Of course, it’s always risky to insert oneself into a colleague’s case, but I think I would’ve said something more like “Marion, I’m wondering if Jack is speaking for both of you. Have these years devoted mostly to work and raising your children drained you both of your sense of vitality and excitement? Do you both long to reconnect in more passionate ways?” After all, it’s noteworthy that Jack didn’t have an affair, and that his fantasy is that they (not he alone) “go to clubs” and reformulate their relationship in a more “open” fashion. He didn’t say, “I’ve had it. I’m leaving.”

None of the clinical and research literature on adult development—from Erik Erikson, Daniel Levinson, and others—characterizes this phase of life as a return to adolescence. Instead, the literature defines it as a new, adult struggle to restore meaning and purpose to one’s life. In fact, Erikson’s seventh and penultimate stage is “generativity versus stagnation,” which I think better characterizes both partners’ sense of stuckness. It also speaks to Jack’s resolution to volunteer at a state park to channel his enthusiasm for environmental protection, as well as Marion’s joining an expressive dance group.

I think Nelson has highlighted an issue critical for many long-term couples who are financially stable, successful in their careers, and have launched healthy, happy children. Basically, it’s grappling with the question Peggy Lee sang so hauntingly about years ago: “Is that all there is?” However, rather than introducing the developmental metaphor of second adolescence, which runs the risk of alienating the couple and making one partner feel he’s behaving like a troubling teen and hasn’t fully grown up, I’d be more inclined to help the couple view the challenges they face as both normal and positive.

Want to earn CE hours for reading this? Take the Networker CE Quiz.

© Illustration by Sally Wern Comport

Tammy Nelson

Tammy Nelson, PhD, Tammy Nelson, PhD, is an internationally acclaimed psychotherapist, Board Certified Sexologist, Certified Sex Therapist and Certified Imago Relationship Therapist. She has been a therapist for 35 years and is the executive director of the Integrative Sex Therapy Institute. On her podcast “The Trouble with Sex,” she talks with experts about hot topics and answers her listeners’ most forbidden questions about relationships. Dr. Tammy is a TEDx speaker, Psychotherapy Networker Symposium speaker and the author of several bestselling books, including “Open Monogamy,” “Getting the Sex You Want,” the “The New Monogamy,” “When You’re the One Who Cheats,” and “Integrative Sex and Couples Therapy.” Learn more about her at drtammynelson.com.

Peter Fraenkel

Peter Fraenkel, PhD, is a couple therapist, psychologist, associate professor of psychology at City College of New York, and professional drummer who studied with Aretha’s drummer. He received the 2012 American Family Therapy Award for Innovative Contribution to Family Therapy, and is the author of Sync Your Relationship, Save Your Marriage: Four Steps to Getting Back on Track, and Last Chance Couple Therapy: Bringing Couples Back from the Brink.