Enjoy the audio preview version of this article—perfect for listening on the go.

My love affair with psychology began in the late ’50s with an undergraduate field trip to Creedmoor Hospital in Queens. The walls were gray and foreboding, but none of that mattered as I sat mesmerized, watching a staff psychiatrist interview a bipolar patient. He announced that the interviewee was a manic-depressive suffering from delusions of grandeur. My first shock was that he proclaimed this openly, as if the patient had neither ears nor feelings. Furthermore, it was clear that this way of “exhibiting” inmates was typical.

As evidence of the patient’s delusional state, the psychiatrist noted that the patient had gone out one afternoon and purchased 10 automobiles. At this point, the patient interjected, pointing out that these were Fords—had he been grandiose, he would’ve purchased Cadillacs. His comment elicited laughs from everyone in the room except the psychiatrist, who remained straight-faced. The patient went on to indicate that although he’d planned to give these cars away to relatives, that deal was off, now that they’d had him committed.

Later in the interview, the psychiatrist asked the patient whether his medications were helping. He replied that if they were, it would be a modern miracle, since he wasn’t taking any of them; however, he added with a wink, the wastebasket seemed remarkably improved. Again, laughter from the group, dismay from the interviewer.

Over the next few months, I couldn’t get that interview out of my mind. Thus, a year or so later, I enrolled in the clinical psychology master’s program at the City College of New York (CCNY). The orientation of the program was Sullivanian, but I remember best a course in interviewing taught by a streetwise social worker. She was fond of reminding us that, as psychologists, we might know all about the ego and the id, but not how to say hello. She was right, of course, and I found her coaching about how to converse with people invaluable—perhaps the best educational experience I’ve ever had.

A year and a half later, I arrived at The Ohio State University to begin work on a PhD. Early on, I met with the program director, Julian Rotter, to discuss transferring my master’s credits to my Ohio State transcript. Rotter—always a smart-ass—expressed doubt that anything I learned in New York could have value. He was fond of labeling the Big Apple “the home of crystal ball psychology.” He reminded me that the agenda at Ohio State was science, not soothsaying and inkblots, but agreed nonetheless to credit my New York coursework, noting that in my case, “it wouldn’t take them too long to undo the damage.”

As it turned out, the Ohio State program was terrific, arguably the best training in the country at the time. Despite Rotter’s jaundiced views, the faculty was admirably diverse, representing a variety of approaches, from classical analysis to existentialism. George Kelly, the creator of personal construct theory, became my first research advisor. He was a superb mentor, who encouraged us to think creatively and follow our instincts, even if our ideas didn’t dovetail with his own interests. On his research team, no project was considered too outlandish to be discussed. Kelly operated on the assumption that the field was far too young to have set rules and regulations: we didn’t know what we didn’t know. Moreover, he frequently expressed the self-effacing view that the usefulness of his own theory could be measured by the speed with which it was replaced by something better.

My First Job

When I graduated, I got an assistant professorship at the University of Rochester. I arrived “fluent” in many different psychotherapeutic languages. CCNY had provided a healthy dose of Freud and Sullivan (as well as three separate courses on those ink blots). Ohio State added a working knowledge of learning theory, personal construct theory, and the “third force” perspectives of Carl Rogers, Fritz Perls, and Abraham Maslow.

At one of my practicum sites, I learned about John Rosen’s practice of reparenting patients by feeding them from a baby bottle. I was also well aware of the radical antipsychiatric perspectives of R. D. Laing and Thomas Szasz.

These eclectic exposures were undoubtedly “good for the soul,” but they left me confused and harboring doubts about the validity of any particular school of thought. I recall a late-night bull session in which a number of us pondered whether therapy was anything more than “the purchase of friendship,” to quote the title of a book that was popular at the time. Did our fancy theories contribute anything to the common sense, youthful optimism, and heartfelt empathy most of us brought to the consulting room? To be honest, I found it difficult to attribute any of my early therapeutic successes—and there were some—to any specific nuggets of professional wisdom.

At the time, the buzz was about the invention of several behavioral approaches. Notable among these was Joseph Wolpe’s systematic desensitization, a method for combating phobias through the use of progressive muscle relaxation. Wolpe was barnstorming the country, speaking at most of the major medical schools. When he visited Rochester, his presentation elicited great skepticism among the psychiatry staff, many of whom believed in “symptom substitution,” the doctrine that if you changed behavior without treating the underlying pathology, new (and potentially worse) symptoms would ensue. The psychoanalytically inclined also dismissed Wolpe’s results as mere “flights into health,” whatever that might mean.

After Wolpe spoke, I found the temerity to speak to him individually. As a young academic hoping to start a research program, I told him I wanted to study the science behind his method. To my amazement, he showed zero interest in any such project. It was only years later, after I’d moved to Philadelphia and gotten to know Wolpe personally, that I understood the cold shoulder I’d gotten from him that evening.

Throughout his career, he was stubbornly committed to his own beliefs and displayed little curiosity about the ideas of others. He’d invite guests to speak at his institute, but interrupt and challenge them the moment they said anything that contradicted the party line. This became such an unpleasant experience that some vowed never to present there again. I recall an institute staff member inviting me to visit, then quickly adding, “Don’t worry, Joe is on vacation that week.”

On the plus side, Wolpe’s single-mindedness is probably what permitted him to invent systematic desensitization in the first place. Anyone else might’ve tried this heretical approach for a session or two but given up on it unless it yielded immediate positive results. Not Wolpe. His tenacity was legendary.

After Wolpe’s visit to Rochester, I tried systematic desensitization with a number of students from the university health service. In my hands, the results were lackluster. I decided that either I was doing something wrong or Wolpe’s outcomes were more attributable to his personal zeal than the validity of his method. Based on that hunch, James Marcia, Barry Rubin, and I published an experiment in 1969 demonstrating that you could violate all the principles of counterconditioning and still get the same results. Others have shown that progressive relaxation—presumably the core ingredient—can be omitted from the procedure without affecting the outcomes.

I should note that many other methods—EMDR comes to mind—have had similar clinical and research trajectories: A strong-minded individual stumbles upon a new idea, usually based on a set of personal experiences or the wisps of a theory. Later, elements that were at first considered essential are shown to be unnecessary or replaceable. Thus, in EMDR, clinicians now sometimes substitute finger taps or auditory stimuli for lateral eye movements. Of course, it’s easy to adjust the theory to accommodate procedural variations. Nevertheless, this sort of methodological fluidity raises doubts about the method’s rationale. From my perspective, it’s likely that systematic desensitization, EMDR, and any number of other approaches work because they shift the beliefs and expectations of the client.

I also began to note that most “miracle methods” lose their effectiveness over time. The usual pattern is that an approach found useful for a narrow set of problems is then recommended for a wider range of issues. At the same time, the number of sessions required to produce results starts to increase. Eventually, the outcomes fall into line with those obtained using other methods, and the miracle status of the method evaporates. Norwegian researchers, for instance, now report that CBT is only half as effective as it was four decades ago. Moreover, enthusiasm for family and solution-focused approaches—once regarded as the field’s salvation—has diminished. One has to wonder how long the field’s current infatuation with mindfulness, attachment theory, and anything neurobiological will last.

Throughout my career, my policy has been to take a serious look at any new procedure that comes along. I even gave Roger Callahan’s Thought Field Therapy a whirl, studying his tapping protocol and listening to him talk. However, unable to reproduce the results he proclaimed, I moved on.

Encounter Arrives

In the late ’60s, as excitement about behavior therapy waned, the human potential movement gained momentum. Newspaper headlines described the nude marathons taking place in the hot tubs of Esalen. Even a town as staid as Rochester couldn’t escape the influence of the counterculture. Thus, I soon found myself participating in several encounter group weekends, and I was elected faculty advisor for the newly formed human relations committee of the university.

I was impressed by the power of these events to rapidly shift how people related to each another. Evidently, when you transported people to a “cultural island,” it was relatively easy to bypass longstanding inhibitions and modify interpersonal norms. Many of the results seemed salubrious—joyful hugging, tearful confessions, and newfound camaraderie. The problem was that once a marathon session ended and folks returned home, their blissful feelings melted away. This seemed to be an ironclad rule: the cultural island made new behavior easier to elicit but harder to sustain. Thus, some group leaders decided to work instead with natural groups, such as executive boards, students in residence halls, playground workers, and city council members. In general, they discovered that working with intact groups produced changes that were more resilient but less impressive.

A number of years later, est—the large-group awareness training developed by Werner Erhard—bumped up against the same dilemma. The training generated striking but short-lived “transformations.” The graduates who profited the most were those who maintained an active affiliation with the organization (or joined the staff).

My takeaway from this era of highly evocative—sometimes thrilling—group encounters is that we’re not the rugged individuals we picture ourselves to be, and our behavior is more closely tied to the social environment than we like to think. This means that social psychiatrist Richard Rabkin was correct when he argued in 1970 that there was no such thing as individual psychotherapy. Therapy is a conversational interface between two subcultures—the subculture of the client and the (professional) subculture of the therapist. There may only be two physical beings in the room, but clients bring with them the influences of family members, peers, work associates, teachers, religious figures, and so on.

Catharsis Celebrated

While the encounter movement was in full swing, another approach gained popularity in the Rochester community: Re-evaluation Counseling, the creation of Harvey Jackins, a former union organizer with no formal mental health credentials. Opposed to consultations with professional therapists and the exchange of fees, he believed that people can and should take turns counseling each other. Thus, he created so-called co-counseling communities, first in California and then elsewhere.

Because his approach emphasized catharsis, co-counseling sessions were noisy affairs, featuring copious crying and gales of laughter, as well as bodily shaking and angry tantruming. Jackins felt that Freud had been on the right track when he experimented with catharsis, but that he’d prematurely abandoned those efforts because his clients’ outbursts caused him personal discomfort. In common with some of today’s trauma-based methods, Jackins believed that people suffered from inadequately processed, stored memories, which needed to be reawakened and reintegrated through the process of “discharge.” Reports of rapid, astonishing results were abundant.

In keeping with my policy of trying everything, I invited Jackins to speak at the university when I heard he was planning a visit to Rochester. He spent a week in town, meeting with our graduate students and demonstrating his methods. I was impressed by his ability to elicit emotional discharge from even the most reserved individuals, and they all claimed to get value from their cathartic cleansing.

However, there was a fly in the ointment. It soon became apparent that many co-counseling clients were becoming catharsis junkies. No matter how much they cried, giggled, and shook, they needed to do more; for them, the cathartic well was a bottomless pit. Jackins, aware of this issue, made changes to his theory. Some patterns, he argued, were “chronics.” Like weeds, they grew back faster than you could get rid of them, and thus they required special handling. One of the procedures he devised for chronics was to have people repeatedly and unreservedly compliment themselves out loud and with a joyous, triumphant expression. Because this kind of extravagant self-praise was experienced as absurd, it tended to trigger even more vigorous bouts of laughter and tears, and would presumably lead to longer-lasting results. I saw no evidence of that.

Although Jackins died in 1999, his organization continues, now headed by his son. But, along with primal scream, rebirthing, and every other cathartic method, Re-evaluation Counseling seems to have faded into the background. I’m now convinced that Jackins was wrong—the success of therapy has very little to do with the release of suppressed feelings. I nevertheless owe Jackins a vote of thanks for inspiring my own research on the mechanisms of tears, which I published in 2012.

What Next?

In 1971, I took a job as director of clinical training at Temple University in Philadelphia. I arrived having had my fill of touchy-feely approaches. Behavior therapy was becoming passé and quickly being replaced by CBT. Michael Mahoney had become a traitor to the behavioral cause, studying with Albert Ellis and Aaron Beck and then founding the journal Cognitive Therapy and Research. Later, he would abandon CBT and join the North American Personal Construct Network, a group dedicated to keeping George Kelly’s ideas alive.

From the outset, CBT struck me as both simplistic and wrongheaded. As research has verified, clients don’t think any less efficiently than the rest of us, except when they’re under stress. When the stress clears up, their thinking improves automatically. Moreover, correcting maladaptive thoughts, one by one, neglects issues of context. Thoughts derive from the person’s narrative, which, as encounter groups have shown, is an integral aspect of the person’s social network. Thus, the focus should be on examining the person’s social framework, not replacing individual cognitions.

In contrast to my reactions to CBT, I was quite intrigued by work on communication theory associated with investigators at the Mental Research Institute at Palo Alto. I “inhaled” Pragmatics of Human Communication when it was published by Paul Watzlawick and colleagues in 1967 and Change: Principles of Problem Formation and Problem Resolution a few years later. At last, we were getting a science-based view that was neither scientistic nor reductionistic.

I noted with some chagrin that Watzlawick and his colleagues distinguished between first- and second-order change—the latter being farther reaching—and that many of the changes I was seeing in my clients were of the former, less impactful variety. For instance, a client would break up with one individual but then date someone who was almost a carbon copy. In other words, although there was a change of cast, the play remained the same: first-order, rather than second-order change.

As I studied the work of the Palo Alto group, I understood that many of their ideas had similarities to notions that Kelly had preached when I was at Ohio State. He’d been interested in how the person’s conceptual world was constructed—not in retraining habits, releasing emotions, or correcting maladaptive cognitions. I confess that when I was at Ohio State, I dismissed Kelly’s approach as being a bit too philosophical for my taste. I preferred Rotter’s social learning theory: it seemed more down-to-earth and even provided equations for calculating clients’ motivations. I still think that Rotter’s writings contain a good deal of clinical wisdom, but I’ve totally reversed my position on Kelly. I now consider his philosophy of constructive alternativism one of the most useful perspectives available—an approach that was well ahead of its time.

The Minnesota Factor

Before saying more about Kelly’s constructivism, I should mention one other set of events that massively affected how I practice. In 1979, the so-called Jim Twins made an appearance on The Tonight Show. Identical twins, they were separated three weeks after birth and brought up by different parents in different communities. They accidentally discovered each other’s existence at the age of 39.

The similarity in their first names is not a mystery: these were assigned at birth by their biological parents. However, other ways in which they were eerily alike are more difficult to comprehend. For instance, each had a pet dog named Toy, and each had been married twice to women with similar names. These extraordinary facts attracted the attention of Minnesota researcher Thomas Bouchard Jr., who decided to begin a formal study of twins raised together and apart. An important conclusion of that project was that twins raised separately were usually found to be more similar than those raised together. This is presumably because twins growing up in the same household are motivated to accentuate their differences.

When I first heard about the Bouchard study, I was teaching an undergraduate course in personality. I was sure that his results, highlighting the importance of heredity, would revolutionize how personality courses were taught and clinical work was conducted. I expected to see massive textbook revisions and witness heated debate at conferences. What actually happened? Basically, nothing. The textbooks remained much the same, and therapists I ran into seemed either blissfully unaware of the Bouchard study or unfazed by its implications, even though the findings contained important insights for our understanding of psychopathology. For instance, a pair of identical twins raised in totally different environmental circumstances developed exactly the same phobic fears and coped with them in exactly the same way.

In my experience, too many therapists still rely on outmoded and incomplete models of personality development. They pay almost no attention to genetic influences and too much attention to the presumed importance of childhood events. Martin Seligman, the former president of the American Psychological Association, carefully surveyed the relevant literature and concluded that neither childrearing patterns nor particular childhood events (including some that would be classified as traumatic) have strong effects on either adult personality or patterns of psychopathology.

In my own practice, I now regularly inform clients about the likelihood that their personality traits have strong genetic components. Clients are invariably thankful to learn, for instance, that they aren’t shy because their parents were overly critical or because they had too few elementary school friends. People come by their dispositions honestly, and there’s no one to blame for their character traits. Moreover, all personality styles have advantages and disadvantages. Therefore, the trick is to maximize the value of the traits you have, rather than to try desperately to become someone you are not. In this context, I often remind clients that Tig Notaro and Steven Wright were both able to become successful comedians despite the vast differences in their temperaments.

The Cybernetic Connection

By the late 1980s, I felt that I’d arrived at a reasonably coherent set of views about therapy. Some of the final pieces of the puzzle fell into place when I became aware of Humberto Maturana’s theory of living systems. His theory, called structural determinism, is grounded in biology and cybernetics. It extends the work of the Palo Alto group and further emphasizes the role of language in our lives. As Francesco Varela, Maturana’s colleague, puts it, “We live and breathe in language.” For Maturana, language includes both words and symbols, and should be considered a complex, communal dance. Although you can’t participate in the choreography without a highly developed nervous system, the dance takes place in the community, not the neocortex.

One implication of Maturana’s theory is that psychotherapy is not and never has been a treatment. It’s a specialized form of conversation—a process more akin to education than medicine. It’s inescapably an influence process—a form of persuasion, as Jerome Frank opined years ago. This does not mean that therapists are cunning manipulators who operate only on self-interest. After all, creating satisfied customers is the goal of any good sales practice. Although many therapists are uncomfortable with terms such as persuasion, it’s a detriment to be in the influence business without knowing it. It’s much better to be clear-eyed about the product you’re selling and the methods you use to sell it.

Maturana distinguishes between social and work relations. Work relations involve a product and imply a hierarchy. By this definition, therapy is a work relation. Therefore, although clients and therapists can be partners, they cannot be coequals. They have different roles to play and different stakes in the outcome. Also, their work has to result in an identifiable achievement, even one as vaguely defined as “an increased sense of well-being.” It requires a specifiable time frame. Therapy that goes on indefinitely, with no discernible goal in sight, should be called something else—perhaps a friendship club or a debating society.

From a cybernetic perspective, system change requires what Maturana calls orthogonal interaction. This means that the conversation with the client has to differ from the kinds of conversations he or she has elsewhere, such as with friends and relatives. Therefore, I often intentionally introduce a novel term or two, or propose a perspective that I don’t think the client has yet considered. As Albert Einstein said, it’s doubtful that we can solve problems using the same kind of thinking we used when we created them.

Because some clients aren’t used to being told the truth, blunt language can often have a powerfully orthogonal effect. For instance, I recall meeting with a young man for two exceedingly painful sessions. Despite asking many questions, I couldn’t put my finger on what was wrong or why he was there. This led me to do some soul-searching before our third meeting. I decided that it would be folly to continue down this seemingly fruitless path, and that a drastic strategy was required. Therefore, at the start of our next visit, I took a deep breath and said, “I have two things to tell you. First, I don’t like you. Second, I don’t believe anything you’ve told me.”

In response, he said “Well, I don’t like you either, and I think psychotherapy is bullshit.”

I replied, “Those are the first two things you’ve said in here that I believe.” We then discussed why he was bothering to see me, given that he considered therapy a crock. He reminded me that I’d seen his wife a few years earlier—she was the one who’d insisted he call me. His basic goal was to prove that he didn’t need—and couldn’t use—anyone’s help. I pointed out that just because his wife found our work together useful didn’t necessarily mean that he and I would make a good team. We concluded that we were wasting each other’s time and decided to call it quits.

About three months later, he called to ask if he could return. This time he was clear about his problems, and we did terrific work together. Moreover, this time I found him quite likable. He explained that the only reason he returned was because of what I’d said to him that day. As he put it, “I realized that I could always count on you to tell me the truth.”

As a general rule, I’m quite polite and diplomatic with clients, but once in a while, a dose of blunt talk works wonders. I’ve learned that clients are far less fragile than they like us to believe, or than they themselves think. I should add that you can’t do your best work if you’re concerned about losing the client. Here’s what Alan Watts says on the subject: “It is a great disadvantage to any therapist to have an ax to grind, because this gives him a personal interest in winning. . . . But we saw, in reference to the Zen master, that he can play the game effectively just because winning or losing makes no difference to him.”

Philological Consulting

Having tried practically every therapeutic modality that exists, I’ve concluded that Szasz was right to consider the term psychotherapy dangerously ambiguous and misleading. He objected to the implication that what we do has any connection to medicine. Instead, he hoped to situate our practices within the domains of philosophy and linguistics. In keeping with his views, I now consider myself a kind of philological consultant.

It’s been said that birds are ensnared by their feet, men by their tongues. My job is help clients free themselves from self-arranged linguistic quagmires. In doing this work, I focus on the present rather than the past. The past is often used to justify the present; however, I consider the client’s current circumstances altogether valid and not in need of any additional justification. Therefore, I can devote my attention to improving the future.

I also focus on beliefs rather than feelings. Feelings are best construed as effects rather than causes. When issues are resolved, the associated feelings change or disappear. I’ve learned not to waste too much time on explanations. Human beings are explanation machines. As they say, we’re rarely “caught with our explanations down.” People can explain whatever they do, especially after the fact. Explanations—even the very best and the most factual—don’t necessarily lead to change. This has been the problem with the analytic emphasis on insight, and it’s required those therapists to coin additional terms, such as intellectual insight, to account for insightful clients who don’t improve.

Being a philological consultant requires attending carefully to clients’ rhetoric. I’m especially alert to their use of explanatory fictions—terms such as low self-esteem, lack of willpower, procrastination, and so on. These are linguistic cons that befuddle both the user and the listener. Procrastination, for instance, is not an illness to be cured. Translated into plain English, it describes individuals who are succeeding at avoiding tasks they don’t like and don’t have to do. (Nobody avoids tasks they must do.) Possible solutions may involve creative social engineering. For instance, a student who “procrastinated” about his schoolwork was able to get more done at the university library, where he felt less socially isolated. A woman who abhorred decluttering her basement transformed the task into something nearly enjoyable by inviting her friend to help and rewarding them both with a dinner out.

These days, the terms anxious and depressed seem to be on the lips of every client who enters our university clinic. Aside from medication, there are no known “cures” for those conditions. Therefore, I’ve found that I can make good progress with these clients by substituting the word frightened for anxious, and sad for depressed. I can then ask what the person fears or finds disappointing.

Getting Off to a Good Start

I want to end by describing how I approach a first session. Often, the key to a successful project is to carefully set the stage for what’s to follow. Thus, the biggest changes in my practice over the years pertain to how I conduct that initial meeting. For instance, I now almost always begin by asking, “What can I do for you?” rather than any of the other possible queries, such as “What is the problem?” or “What is troubling you?” This opening question puts the spotlight right where I want it: on how the client construes the job I’m being asked to accept. Even a reply such as “I don’t know” provides useful information. As my social-work instructor frequently said, you have to begin where the client is.

The most important goal of the initial session is to establish a solid working contract. To that end, I intentionally call attention to a few points on which the client and I are in agreement. I also point to one or two issues about which we disagree. I’ve learned that clients like to feel understood, but they also like to be challenged. I want to communicate from the outset that in our work together, I’ll be bringing fresh ideas to the table.

Before the first session ends, I inform the client about ways in which working with me will be different from working with other therapists. For instance, I pay less attention to the clock than others. Whenever possible, I like to end a session at a logical stopping point, rather than because an hour has elapsed. I’ve had sessions as short as 10 minutes and as long as three hours, but I charge the same amount regardless of the length of the meeting. It’s the project that matters, not the amount of time we spent discussing it. I hasten to add that excessively short or long sessions are the exception; much of the time, my sessions are of conventional length.

I avoid scheduling sessions at regular intervals. I’m convinced that doing so conveys exactly the wrong message. My meetings with clients are for determining the next steps in the project. This might require getting together a few days later or perhaps not until the following month. My expectation is that the important work will go on between sessions. But I never use the term homework to refer to between-session tasks. Particularly for a philological consultant, words matter, and for many people, homework has dreadful connotations.

Toward the end of the first meeting, I propose a tentative plan that includes at least one specifiable goal and, if possible, an accompanying time estimate. For example, I might say, “What if we focused on the problems you’re having at work? If, after a month of working on this, you felt comfortable meeting with your supervisor, would you consider that a worthwhile accomplishment?” If the client says yes, then we have a working agreement. The scope of the work might be further refined later, but at least we have a place to start.

Even if all has gone well, I don’t immediately set up a second appointment. Instead, I invite clients to go home and think about what transpired. I want them to decide whether or not they got value out of our meeting. (If it’s a couple, I ask them to make that determination separately.) I want them to make this evaluation after they leave, so that it’s free of the demand characteristics involved in being each other’s presence. If, at home, the clients decide that we’re a good team, they can call to set up a second meeting. If they considered our session a dud, I’m happy to provide referrals to other clinicians.

When I first began requiring this additional “vote of confidence,” I thought the process might cost me a fair number of prospective clients. In fact, over the years, fewer than a handful of clients have chosen to go elsewhere. Requiring that clients make a deliberate, considered declaration of intent has yielded untold benefits. If and when the relationship hits a rocky patch, I can remind the individual that he or she signed up for the journey.

I should add that I never “terminate” clients. I consider termination an ugly word. Human beings are not good at handling separations, so why create any more than you need? When I have a fever, I go to see my physician, but when the illness ends, he doesn’t “terminate” me: I’m free to return for additional services whenever the need arises. I use a similar model. Clients can return at any time for advice about some new issue or for a refresher course about something we previously discussed. I’m always delighted to hear from clients I haven’t seen in many years, even if it’s just an email greeting or holiday card.

It’s been an exciting but bumpy journey from Neo-Freudian to philological consultant. I wish I’d realized earlier that the term psychotherapy is a category mistake—a misclassification that makes it more difficult to be clear about what we do. But I’m satisfied with where I’ve landed, having learned that clients don’t necessarily need new answers to their questions—they need new questions. It’s the old ones that keep them rattling back and forth, stuck in the same linguistic ruts. In the end, I’ve had gratifying success with my current approach, which aligns with the maxim of Adlerian Harold Mosak, who’d tell trainees that although he didn’t always know what to do, he knew that there was always something to be done.

ILLUSTRATION © JAMES ENDICOTT

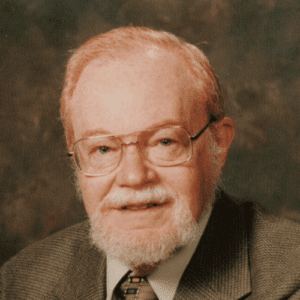

Jay Efran

Jay Efran, PhD, professor emeritus of psychology at Temple University. He received the Pennsylvania Psychological Association’s 2009 award for Distinguished Contributions to the Science and Profession of Psychology and is co-author of Language, Structure and Change and The Tao of Sobriety.