Enjoy the audio preview version of this article—perfect for listening on the go.

In the late 1890s, Sigmund Freud, then a highly respected neurologist, abandoned his attempt to create a “scientific psychology” grounded in neuroscience because knowledge about the physical brain was just too primitive. Instead, he had to settle for studying the processes of the mind, which didn’t turn out too badly, considering he virtually founded the entire field of modern psychotherapy. Now, a century later, Freud’s abandoned dream shows signs of resurrection. An unprecedented outpouring of discoveries in brain science are beginning to affect how therapists think about and practice psychotherapy—possibly bringing the most significant transformation in our field since the invention of psychoanalysis.

We believe we’re seeing a dynamic new understanding of how psychotherapy works and how it actually affects the neurophysiology of our clients. We call this new vision of treatment “brain-based therapy,” a way of approaching the therapeutic task that draws upon a combination of neuroscience, developmental psychology, psychotherapy research, and complexity theory. While all of this may sound complicated, it carries forward the single most important and powerful aspect of traditional psychotherapy: a healing conversation that transforms mental and emotional suffering. What we’re discovering about neuroscience promises to help us understand the question that’s beguiled therapists from the beginning: How can a simple conversation—or, as Freud called, it the “talking cure”—change the brain?

This potentially revolutionary new era represents a decided break with therapy as we know it, and particularly with the mainstream therapy of the last 30 years. During the last three decades, a medicalized view of how to think about, classify, and treat mental and emotional problems has become the default therapeutic position for the field. We refer to this institutionalized therapeutic worldview as “Pax Medica,” a term adapted from the Pax Romana—the 200-year period of relative peace and conformity that the Roman emperor Augustus initiated among the far-flung lands of the Roman Empire in 27 B.C., thus halting many decades of civil wars, foreign invasions, and other threats to harmony and good order. Like the Pax Romana, the Pax Medica brought a sense of stability, coherence, and legitimacy to the then-fragmented culture of therapy, but it created its own hegemony—heavily influenced by the medical model—which has dominated the therapy field down to the very language we use to describe our work.

The Pax Medica would have seemed an unlikely development during the first 60 years of the 20th century, when psychoanalysis and psychodynamic therapy were just about the only game in town. Indeed, if you had a mental health problem prior to the later 1960s, you generally spent years uncovering subconscious drives, conflicts, repressions, and transference dynamics with a studiously neutral, analytically trained therapist. Those with severe mental illness, not considered “good candidates” for analysis or psychodynamic therapy, received draconian, physical treatments—electroshock, ice baths, insulin treatment, neurosurgery, and lobotomy. In neither category of treatment—soft or hard—did anybody appear to give the least thought to the completely mysterious, indecipherable, and largely irrelevant object located behind your forehead.

By the late ’60s, however, the old models were beginning to lose their magisterial dominance. While most of Freud’s professional heirs, unlike Freud himself, showed, at best, blithe indifference to empirical inquiry into whether their methods actually accomplished anything, in the early 1950s, one maverick experimental psychologist, Hans Eysenck, actually researched the question, “Does analytically based therapy work?” After reviewing the outcome literature, such as it was, he came out with the scandalous answer, “No!” Psychotherapy, he wrote, showed itself no more effective “than the mere passage of time.” Unsurprisingly, the establishment paid no attention to him at all.

But traditional psychoanalysis already was becoming something of a dinosaur, replaced by a buzzing, blooming confusion of different therapies, many led by therapist-celebrities—Carl Rogers, Fritz Perls, R. D. Laing, Milton Erickson, Virginia Satir, Salvador Minuchin—who held their distinct approaches—client-centered, existentialist, humanistic, Gestalt, narrative, cognitive, and variants thereof—as distinct fiefdoms, without much attempt at real dialogue or integration. By the 1970s, with the growth of cognitive-behavioral therapy and the proliferation of different therapeutic approaches, it began to look as if anybody who wanted to do anything anytime in the name of “psychological healing” could claim to be doing therapy. The field was beginning to resemble a kind of Woodstock Nation for psychotherapists.

To this therapeutic melee, Pax Medica brought a sense of order, discipline, coherence, and professionalism.

The Rise of Pax Medica

The Pax Medica originated with three signal events that happened within a few years of each other: the invention of Prozac, the blockbuster drug that appeared to offer a quick, dependable, chemical fix for depression; the publication of DSM III, establishing a formal diagnostic classification system for emotional and mental problems conceived as illnesses; and the advent of evidence-based therapies, which required treatments to have clear, reproducible guidelines and solid, empirical support.

While the first tricyclics were mildly successful, it was the advent of Prozac in 1974 that changed everything. Prozac shifted psychiatry away from a focus on memories, fantasies, dreams, and projective identifications toward a fascination with all things pharmaceutical. Part of Prozac’s success was based on the appealing, somehow biological-sounding notion that it corrected “chemical imbalances” in the brain, and at first glance, controlled trials appeared to prove the theory behind the product. Even today, more than 30 years after its first appearance, Prozac remains hugely popular around the world. In the U.S. alone, millions of prescriptions annually are written for the drug’s generic version—and newer antidepressants are even more widely prescribed. In the U.S., 1 in 20 men, and almost 1 in 10 women, uses an antidepressant.

The concept of medical treatment for psychological problems had wide support in the popular culture. There was an obvious appeal for a simple pill to “fix” one’s depression, rather than enduring endless therapy. The idea that, along with your yearly physical, your primary care doctor could tweak your “chemical imbalance” and put an end to your depression was virtually irresistible. Medicinal cures for psychological problems are a quintessentially American solution—fast, easy, simple, efficient, and new. Psychodynamic psychotherapy, by contrast, appeared quaint, slow, tedious, and old-fashioned—a bit European.

After Prozac, psychotherapy itself had to change in order to survive in competition with a magic, little pill. What would save the therapy enterprise from sinking like a stone?

Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) was one answer. During the 1970s, psychiatrist Aaron Beck developed his CBT approach and used the methods of social science research to establish its indisputable empirical effectiveness. Many therapists disdained the social science research methods that underlay psychotherapy outcome research, what there was of it, but Beck viewed the use of research as an opportunity to build scientific credibility for CBT. For potential customers, the method had instant appeal. In contrast to psychoanalysis, CBT was fast (12-16 sessions), focused, pragmatic, optimistic, rational, and unconcerned with deep, subconscious motivations. It was a sunny field to psychoanalysis’s dark cave.

Like other therapists of the time, Beck ignored the brain and made only rudimentary assumptions about how the mind worked. For him, a precisely defined and designed technique was what mattered most, not complicated theories about the inner processes of the mind. But he did consider himself a physician, the people who saw him patients, and his therapy a mental health treatment.

Beck’s work dovetailed seamlessly with a new version of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-III). In it, the editor, psychiatrist Robert Spitzer, identified what were to become some of psychiatry’s “greatest hits”: panic disorder, AD/HD, and major depression. In a field fraught with complexity and ambiguity—and in a world where enormous amounts of money were at stake—Spitzer offered mental health professionals some peace, simplicity, and the comfort of a renewed faith in authority. His tome rapidly became the “bible of psychiatry” for insurance companies, the disability and criminal justice systems, and researchers seeking government approval for new drugs.

The collective influences of Spitzer, Beck, and the pharmaceuticals resulted in a compromise vision of what the “mental health profession” should be and do, which has dominated the field since the late 1970s. This Pax Medica stipulates that in psychotherapy, as in dermatology or orthopedics, diagnosis—which assumes a specific pathology—is vital to evaluating a patient and planning treatment. In standard medicine, in the absence of observable causes—lesions, virus, or bacterium—treatment targets the symptoms. Likewise, the new view of therapy required clinicians who were formulating treatment plans for their patients to ameliorate the symptoms associated with specific diagnoses to determine medical necessity.

As an indication of how thoroughly the medical model penetrated mainstream psychology, in the mid-1990s, the Society of Clinical Psychology of the American Psychological Association (APA) established a task force on “empirically validated treatments.” To earn the designation “empirically validated,” a treatment had to be shown superior to placebo or comparable treatment in two separate randomized clinical trials. The intervention had to be reducible to a clear and teachable manual. Eighteen DSM-III disorders were seen as candidates for this process; almost all the methods that initially qualified as “evidence based” were variations on CBT.

There were soon rumblings of skepticism and discontent with the established regime that was Pax Medica. In 1980, just four years after the publication of the DSM-III, three little-known academics—therapy researchers Mary Lee Smith, Gene Glass, and Thomas Miller—combined and analyzed the results of many well-designed studies on the benefits of therapy and reached two unexpected conclusions: notwithstanding its bad rap, psychotherapy was robustly effective. Even more startling—and totally at odds with the spirit of the times—the actual technical methods—considered aside from the impact of the therapeutic relationship itself employed by therapists—seemed to have no significant effect on outcome. Since then, the 80 to 90 percent of psychotherapy research examining the efficacy of specific methods for specific disorders has corroborated their findings. Overall, skepticism about the singular importance of diagnosis and method has increasingly taken root since the 1980s—even the alleged superiority of CBT is being questioned by a sturdy body of dissidents within the profession.

Reconsidering SSRIs

The pharmaceutical companies have promoted the idea that “chemical imbalance” is the cause of depression and massive marketing has convinced millions that they can cure it by manipulating their neurotransmitters. But if psychotherapy research has eroded the conviction that there’s only “one method” for conducting successful psychotherapy, a new, harder review of drug research over the past decade has likewise undermined the simplistic, “one-factor” theory of antidepressant action. Even the “empirical proof” for the effectiveness of medications is now considered suspect. In 2008, Erick Turner and other researchers at the Oregon Health and Science University subpoenaed the FDA to release all the studies on antidepressant effectiveness in its archives. Because science journals prefer positive findings over negative ones, Turner and his colleagues were unsurprised to find unpublished studies concluding that SSRIs are no more effective than placebo.

But they were astonished by the number of such negative studies. Research reporting positive effects for antidepressants was 12 times more likely to be published than studies reporting negative results. Turner et al. concluded that publication bias had inflated the common impression of the effectiveness of SSRIs by about a third overall, and for some medications, the figure was twice as high.

Indeed it now appears that the early widely touted success of SSRIs was based on an overly simplified methodology and cherry-picking of results. Recent large-scale reanalysis in 2006 of the studies of efficacy of SSRIs indicates that these agents are effective between 56 to 60 percent of the time. Since one recent metanalysis in 2005 by Bruce Arroll and others shows that between 42 and 47 percent of subjects respond to a placebo, an effect 10-15 percent greater than placebo hardly justifies psychiatric and popular confidence in SSRIs as the first-line treatment for one of the most common mental disorders. In a 2006 Scientific American study aptly entitled “Antidepressants: Good Drugs or Good Marketing?” David Dobbs reported that, partly because of the simplistic “one-factor/chemical imbalance” model of depression causation, only 50 percent of all drug trials over the past century were published or reported—basically, only the ones with positive outcomes.

In 2006, three enterprising psychologists, Kevin McKay, Imel Zac, and Bruce Wampold found striking evidence for the importance of the therapeutic relationship by obtaining and reanalyzing data, paradoxically enough, about the effectiveness of medications. A major study by the National Institute of Mental Health’s Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program, which focused on different approaches to depression—but did not even include the therapeutic relationship as a variable—compared the effects of the antidepressant imipramine with a placebo. The published results heralded the power of the pill. In the reanalysis of the study by McKay, Zac, and Wampold, however, it became apparent that the most effective psychiatrist actually got better results with placebos than the worst-performing psychiatrist got with antidepressants.

Brain-Based Therapy

It’s been more than a decade since the first serious discussions of the clinical relevance of neuroscience began to appear in our field. Since then, once-mysterious terms like amygdala and hippocampus have become part of the common parlance of any reasonably hip therapist who presumes to be current with psychotherapy’s latest trends. But are we ready to go beyond merely parading our more scientific-sounding professional jargon to showing that, in fact, brain science can profoundly impact the direction of clinical practice? To be sure, some critics argue that little has actually changed in the theory and methods of our field because of neuroscience. They dismiss therapists’ increasing interest in the brain as yet another example of our endless search for novelty and our compulsive need to put old wine in shiny, new bottles. Where, they ask, is the research that demonstrates that talking about the brain with clients makes for more effective interventions or that new clinical methods coming out of neuroscience can extend and deepen our impact?

But to truly grasp what neuroscience means for the future of psychotherapy, it’s important to recognize just how new ideas and fresh perspectives enter into a profession and transform it at a number of levels, some immediately apparent, some more abstract and obscure. The increasing role that neuroscience is likely to play in the psychotherapy field of the future will not be limited to the immediate, practical benefits of innovative interventions or mind-spinning advanced technologies. To assess what the new era of a more brain-based practice will be like, it’s necessary to start by looking at how it’s likely to change the perception of our profession, as well as the way it’ll alter the way we perceive both our clients and our own clinical role.

Let’s begin with the knowledge base that underlies everything we do. For much of its history, psychotherapy has been awash in metaphors to describe the illusive reality of how the mind works and why it goes wrong. We already know from empirical evidence that lots of therapy methods and models help our clients. Yet in the absence of specific information and insight about the physical brain, our ideas about why they help and how they affect the brain have been largely “just so” stories—plausible sounding, but unverifiable, theories and explanations—about what we think or imagine is going on inside the black box of the skull.

In the increasingly competitive world of health care, that isn’t likely to be enough to make the world continue to take us seriously. Brain-based therapy promises not only to change the way we think about therapy, but also the way the entire healthcare field thinks about therapists. It’ll draw its methods from neurobiology, evidence-based practice, and attachment research, thus bringing psychotherapy more fully into the scientific community.

We now know from neuroscience and attachment research that interpersonal relationships profoundly affect the physical structures and processes of the brain. Indeed, neuroscience tells us that our brains are exquisitely social in nature—as a species, we’re constantly getting into each other’s heads, affecting each other’s moods and emotions, rewiring each other’s neural networks. Therapy works primarily as a nervous-system-to-nervous-system regulator (like mother to child, mate to mate, friend to friend) that helps clients ramp down their own brains’ arousal levels and reactivity, as well as activate their neural capacity for regulating their own emotions.

This fact alone makes it very difficult to dismiss old-fashioned talk therapy as some sort of feel-good, fuzzy-wuzzy, amorphous, non-scientific sideshow to the purportedly “real” mental health care provided by Pax Medica. In fact, as we understand better how to influence the subtle, deep, infinitely complex interpersonal communication between therapist and client, it’s easy to imagine that the status of the therapeutic relationship as perhaps the most powerful of all clinical “interventions” will increasingly be recognized within the larger healthcare system. Instead of an expression of an “alternative ” view of health care, more and more the future of an increasingly cost-conscious healthcare system will revolve around an acknowledgment that the mind directly affects the body and vice versa—in a real sense, mind is body is mind. This means that mind-body approaches—nutrition, physical exercise, relaxation techniques, yoga—will most likely be integrated into any necessarily “holistic” approach to wellness. Who knows? Such a perspective might even have an impact on the medical establishment, convincing doctors to spend more time exploring the role emotion and relationship play in the health or illness of their patients!

Brain-based therapy is unlikely to do away with the major schools of therapy—primarily CBT and various psychodynamic approaches—which have given most of us the basic tools we use in daily practice. What will be different, however, is that the therapeutic focus will begin inside with the client’s brain, rather than outside with a set principles and practices from one of the dominant “clubhouse” therapies (the current schools of therapy that are like exclusive membership organizations). In other words, therapy drawn from an understanding of the brain will enable clinicians to escape once and for all what might be called the “theory pit.” There’ll be no point to declaring fundamental allegiance to any one “theoretical home” when our primary focus is on the brain. This meta-perspective will increasingly help therapists evaluate which approaches might work best with a particular client at a particular point in therapy to resolve a particular symptom or difficulty by activating a particular brain process. We’ll be in a position to more effectively integrate a variety of new and old models as it becomes more apparent that what ultimately counts is what changes the brain.

Brain-based therapy has already broadened and deepened the perceptual field of many clinicians beyond the limited, overly cerebral “psychological story,” that’s so often been front and center in the attention of the therapist. It’s a temptation of talk therapy to conceptualize everything our clients bring us in terms of the unfolding of a narrative mediated by spoken words, theirs and ours. Yet while the left brain gets a real workout in the standard therapeutic exchange, much of what drives us as human beings is unspoken, even literally unspeakable—emotional and physiological states of arousal that transcend our partial psychological stories, often going unrecognized and unheard in a word-dominated field. Indeed, little human experience can be apprehended through rational, conscious, verbal language. Brain-based therapy allows us to tap into the many other forms of personal expression—physical, emotional, spiritual—to gather information about our clients and bring into therapy a host of nontraditional modalities with an undeniable impact on the brain—meditation, of course, but also dance, music, and the visual arts.

Neuroscience offers therapists the opportunity to truly see and understand the neurophysiological wiring and activity underlying states of fear, shame, anxiety, depression, and addiction. Such a perspective provides a much bigger, more capacious view of human beings, including those humans sitting across from us, than any single therapy model allows. Rather than comprising a particular narrative—the psychodynamic narrative of unconscious motivations and repressions, the CBT narrative of entrenched cognitions driving emotions, the family systems narrative that individuals can only be understood in the context of family relationships—brain-based therapy implicitly encompasses them all, without making a religion of any. At the same time, paradoxically, it provides a more empirical, precise, and parsimonious explanation of the client’s difficulties. In other words, it offers us the opportunity to wed the soft art of the therapeutic conversation with the exacting hard science of the brain.

We’re well aware that marriage of brain science and therapy is still in its earliest stages and, at this point, practitioners like us who are interested in building bridges between the two are still experimenting, drawing what we can from our understanding of neuroscience and sifting through psychological theory and research to find common denominators appropriate both to our clients’ psychological situation and to what appear to be the relevant brain processes. In our own work, our first brain-based “intervention” with our clients is simply to talk to them about their own brains—terra incognita for most people—and explain how therapy can help them rewire their own brains so that they feel better and get more out of life. We include information about the brain at every stage of therapy, from assessment to goal-setting to the selection of interventions and the moment-by-moment corrections in our alliance with clients.

Clients find that putting their distress into a biological context externalizes their problems, reduces shame and guilt about admitting something is “wrong” with them, and quickly lessens resistance to therapy. We say, in effect, “We’re going to work together to rewire your brain so that your amygdala won’t hit the panic button when there’s nothing to panic about.” By explaining the importance of relationships in changing the brain at every point in their lives from infancy to old age, we implicitly make the point that therapy must itself be a genuine relationship and collaboration to succeed. More subtly, bringing the brain into therapy acknowledges the biological heritage we all share.

Transforming the Therapeutic Experience

We all know that use of the therapist’s self is critical in therapy and that therapy, like any good relationship, implies mutual emotional regulation. In psychodynamic parlance, a good therapeutic alliance balances the powerful tides of transference and countertransference, while maintaining a vital, but controlled, sense of mutual emotional attachment. Knowledge of brain science makes explicit the neural underpinning for this mutual regulation (and dysregulation), helping us attend to this inner dialogue, both aurally and somatically, with more awareness and skill.

A client we’ll call Ilyana came to one of us after a family catastrophe: her son had murdered his wife and was serving a life sentence in prison as a result. The court had awarded custody of the grandchildren to the daughter-in-law’s mother, who refused to let Ilyana see them. In one blow, she’d lost her daughter-in-law—whom she adored—her two grandchildren, and, in effect, her son. These traumatic events reactivated the brain-based patterns that were the legacy of her upbringing by a harsh, puritanical mother and an alcoholic father, a pattern reinforced by three episodes of major depression in her adult life. Her brain had learned how to be depressed even before the current traumatic losses and stress. In her distress, she’d cut herself off from nearly all her family and friends, she’d become extremely nervous and felt she couldn’t handle even the smallest setbacks, and, overall, felt desperately low.

Having grown up in the era of the Pax Medica, I (LL) was expert in diagnosing Ilyana’s problems. As a specialist in evidence-based treatment and psychotherapy research, I was also reasonably expert in the techniques managed-care case managers would like me to use to help her—primarily medications and CBT. But I knew all too well that a straight DSM diagnosis often misses much about the client’s character and situation. As a result, the conventionally correct “treatment” plan frequently ends in failure.

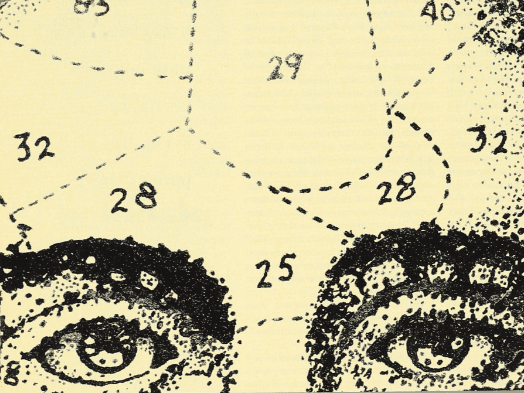

Sitting with Ilyana, I visualized her brain thrown into a crash dive by her daughter-in-law’s murder and the loss of her grandchildren. Acute stressors flood the brain with the stress hormone cortisol and change its metabolism and eventually its morphology. As her amygdala becomes more active, a nearby module, the hippocampus, likely becomes less efficient. The hippocampus is like a librarian, taking in the welter of sensory information about the outside world from many different parts of the brain and organizing it in forms that can be explicitly remembered. Rich in receptors for cortisol, the hippocampus acts like a thermostat during periods of normal stress and turns down the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, in effect, shutting off the alarm caused by the amygdala’s reactions.

But chronic cortisol elevations—an inevitable consequence of severe, long-term stress—can erode the hippocampal functioning. Chronic stress can actually cause the hippocampus to shrink, impairing a person’s ability to attend to and remember what’s happening in the outside world. When this happens, the healthy push-pull equilibrium between the amygdala and the hippocampus (in which the amygdala promotes sympathetic arousal, including the eventual release of cortisol, and the hippocampus down-regulates it breaks down. It seemed to me that that this dynamic was at the bottom of Ilyana’s constant feeling of being on edge and her overreactions to ordinary stressors.

What Ilyana told me about her years growing up—and what I experienced as her attachment-based insecurity during our therapy—suggested that her brain had coped with excessive levels of cortisol for nearly her entire life. Over time, these dynamics had resulted in an unusual vulnerability to depression: her hippocampus had lost some of its ability to take in features of the outside world, her overactive amygdala promoted a more or less continual sense of danger and vulnerability; and right-brain dominance biased her cerebral architecture toward a set point of sadness and melancholy. Since Ilyana regarded any ambiguity as threatening, she readily interpreted the ebb and flow of changing facial expressions and tones of voice in others as signaling catastrophe.

On a recent vacation, she became acutely anxious and depressed after a spat with her boyfriend, who’d accused her of looking to him “for a kind of security that a person can only find in themselves.” Ilyana was convinced the relationship was doomed because “I’m so screwed up. I hate being alone, but with my luck, this is how I’ll end up: alone.” From a kind of crouched position in her chair, she looked up at me and asked pleadingly, “How can I come to grips with things so I don’t feel so overwhelmed all the time?”

After saying this, she dissolved in tears and curled up in her chair, withdrawing from the world. I looked at my watch and thought about the friend I was planning to have lunch with. These attempts at self-distraction made me aware of my own agitation. To recover a sense of inner calm, I deliberately slowed down the process, asking Ilyana how she’d felt after this encounter with her boyfriend.

“How I felt when I was alone? It’s . . . a longing . . . really deep longing . . . . I’m afraid. I remember feeling this even as a child, when my parents would fight and I’d worry that they were going to break up.” I asked her if there was ever a time in her life when she didn’t have this feeling, or it wasn’t so intense. She said, “Yeah, when Ivan [her husband] was alive, things were fine then. But with what my son did and all that’s happened to me—Ivan’s death, losing the grandchildren and Dolores [her daughter-in-law]—it’s the worst possible life for a person like me, who gets these awful feelings being by myself. I don’t want this life any more. I don’t want to be alive.”

My mind and heart jumped with these last words, and I thought about a suicide attempt she’d made after the death of her husband. Could I help her come out of this tailspin or did she need to be hospitalized immediately? At this point in the hour, I recognized with some alarm, Ilyana was regulating my brain more than the other way around.

Regrouping, I thought about the second critical issue, after the brain, when working with dysregulated clients like Ilyana: attachment. In fact, her boyfriend was on the mark. Her insecurity and high levels of depression and anxiety had precipitated one of those self-fulfilling prophecies that beset the anxious and depressed: a narrowing of the one good relationship she had in her life. If I wanted to override my own anxiety and stay emotionally attuned to her, I needed to find a way to more fully engage with her in the moment. Rather than just thinking about the severity of Ilyana’s problem. I needed instead to speak to her feelings without “catching” her pessimism and hopelessness. After all, the therapeutic relationship is based on the brain’s capacity to understand, and to regulate, the emotional states of others. Our ability to acknowledge and mirror these states in others (through the signs of autonomic arousal that underlies another’s unhappiness, stress, and anger) is sometimes all that makes human life bearable.

I told Ilyana that her feelings about being alone and her fear of ending up suffering alone were understandable. How could she not feel that way, given what had happened to her? “When you say that you don’t want to live anymore, is it that you want your life to be over or is it that you want this feeling to end?” She shook her head and looked lost.

I said “Let me tell you what I was thinking earlier when you asked me how you could stop feeling so overwhelmed. All of us have these intense and painful feelings because our capacity to feel despair when terrible things happen is wired into the architecture of the brain. When you’re feeling very sad or trapped and pessimistic, then you withdraw and the right side of your brain right behind your forehead becomes much more active. The right side produces feelings that are so huge you feel trapped inside them—they blot out everything else.”

Just telling Ilyana what I understood about her suffering helped me feel more present, and, as I spoke, she seemed steadier and more focused; she looked at me directly, expectantly.

“Feelings work like a normal curve,” I said. “They might begin with something small, like a sensation of discomfort or unease, and then get bigger until we become consciously aware of them as full-fledged emotion. What your boyfriend said to you was relatively small—part of a spat, really. If you hadn’t been so overwhelmed at the time by other things, the remark might have annoyed you, but not ruined the trip. That’s the way it’s supposed to work—a feeling starts off small, builds up to some level of intensity, and then begins to subside. But with these huge feelings, your left side of the brain attacks the feelings like a white blood cell attacks a bacteria: it latches on to it and tries to control it. At such moments, it attacks your despair with thoughts like ‘I’ve never been able to be alone!’ ‘What’s the matter with me?’ ‘Why do I do this to myself?’ ‘The older I get the more I’m going to be alone.’ ‘I don’t think I can stand it if I die like this!'”

By this time, Ilyana and I were looking directly into each other’s eyes and leaning in toward each other—it felt to me as if we were on the same wavelength. She said, “I want to write this down. I’m not sure I’m going to remember it. It feels important.”

I said, “I’ve been talking a lot today and I want to come back to you. How are you feeling right now?” Pausing, as if waking up, she said, “I feel better. I feel calmer. I see what you’re saying; what my boyfriend said wasn’t that big a deal. I’m feeling better now. I don’t know how I’ll feel when I’m alone again, but, right now, sitting here with you, I’m feeling better.”

For me, that moment with Ilyana lies at the heart of the experience, incremental and uncertain as it often is, that therapy is all about. Somehow in the course of a session, a client finds a way to tolerate something that a few moments before seemed intolerable. Through the give and take between client and therapist, as in all relationships in which soothing and healing takes place, something shifts in the nervous system of both parties. The particular challenge of therapy then becomes how to take that immediate experience of calming or release or insight and turn it into an expanded capacity for self-regulation that goes beyond our consulting rooms. To be sure, brain-based therapy didn’t invent the profound impact that a relationship can have on the brain, but it does provide a new language and a new map for guiding clients through both the intensely emotional encounter with their darkest demons and the more long-term process of rewiring their own nervous systems as they move toward greater well-being.

Since that first session with Ilyana, our growing bond with each other has enabled her to feel the immediate support of our relationship, while also understanding and absorbing the link between the fundamental principles of brain science and the changes she’s experiencing—for instance, the fact that experience itself can generate new synaptic connections to create new neural networks. She’s come to recognize in both the safety of our encounters and by taking that experience back into her life that, without altering the nature of her relationships with other people, it’s likely that her habits, patterns of behavior, and moods will remain the same, as her neural networks continue to run in the same grooves—or ruts. But as she discovers new ways to think and behave when feeling troubled, she keeps finding within herself the basic truth of the neurobiological principle that “what fires together, wires together.” She’s also learning that becoming securely “herself” means allowing her brain to be nourished by her connection with others.

In addition, Ilyana is realizing that brain-based therapy is, in a sense, rooted in a kind of neurobiological athletics. As she understands her own brain better, she’s training herself to use her brain more effectively. Like a tennis or golf pro, she’s developing an informed sense of what moves she should make to best improve her “game” and the practice necessary to sustain them. And because she now feels she has more control over how her brain functions, she has a greater sense of agency in running her own life.

As Ilyana’s mood has shifted, she’s begun making better life choices—changes that are perhaps no different from what would have happened in many therapies not specifically informed by neuroscience. But a brain-based approach certainly has offered both of us a map through the sometimes bewildering twists and turns of the therapeutic process. When I’ve felt off track in my work with her, principles of neuroscience and attachment research have helped me focus on aligning my own internal state with hers, discovering how to renew my engagement with her in the moment to moment flow of a session in a way that’s at once what any sensitive therapist might achieve and subtly different.

The brain-based model provides a framework to check in with oneself about what’s being attended to and what might be neglected in a session. Are you spending too much time thinking about what’s emerging from the client’s left prefrontal cortex and temporal lobes—the speech centers that power the life narrative—and not paying enough attention to the client’s posture, tone of voice, gestures, and other nonverbal cues? Or are you so caught up in the dance of mutual regulation that’s going on between the language, the facial expression, the mirror neurons, and other biological facilitators of empathy that you neglect thinking about psychological theory or concrete behavioral interventions that might help the client begin rewiring his or her own brain? No doubt, there are many ways to help a client like Ilyana, but we’d wager that the work of any therapist would be enhanced by starting to think in a way that leaves the Pax Medica behind.

Conclusion

A decade and half after the first serious attempts to see the connection between neuroscience and therapy, we’ve learned that the more we study the human brain, the more profoundly and even mysteriously human we seem. We’re discovering that all the technical means that once were presented, one after the other, as having revolutionary possibilities for curing emotional maladies—strict diagnostic categorization, neurosurgery, electroshock, drugs, behavioral methods—massively underestimated both the brain’s power and its resistance to simplistic answers to complex human issues. In fact, we’re discovering that far from reducing the human “self” to a kind of neurobiological terrarium as was originally feared, brain science is demonstrating that the stuff between our ears is even more distinctive and awe-inspiring than we thought.

Perhaps the most astonishing finding of brain science—something we never anticipated—is the way the human brain, in concert with other human brains, is constantly in the process of self-renewal and self-creation. Through a combination of genetics, developmental history, social and economic circumstances, relationships, and our own conscious, unscripted efforts, we’re both determined and self-determining. The most critical, indispensable element in this multidetermined/self-determining brain-building process seems to be something that, to varying degrees, we share with other mammals, but have taken much farther than our evolutionary cousins in the animal world: the brain’s need and desire for dependence on relationships with others of our kind. We write “brain” as a singular, but in a real sense there’s no such thing as one, single brain—only brains and nervous systems in some sort of relationship to one another.

Therapy is at its root a brain-changing relationship, and we’re just at the beginning of a new phase of development within our field in which that realization is becoming more specific, concrete, and grounded in the ever-increasing knowledge base of neuroscience. We’re coming to recognize that, as therapists, we’ve always been “brain scientists”—we just never had the tools, the words, and the concepts to articulate it before.

Lloyd Linford, Ph.D., is director of Psychiatry and Chemical Dependency Best Practices for Kaiser Permanente’s Northern California healthcare system and chair of Kaiser’s annual psychiatry conference. He’s the coauthor of the Brain-Based Therapy book series and editor of more than 30 other volumes. Contact: lloydlinford@yahoo.com.

John Arden, Ph.D., is the director of training in the Mental Health Division of the Kaiser Permanente Medical Centers, Northern California Region. He’s the coauthor of the Brain-Based Therapy book series. Contact: john.arden@kp.org.