What are the defining characteristics of the cognitive therapy approach to depression?

Judith Beck: The hallmark of cognitive therapy is understanding clients’ reactions—emotional and behavioral—in terms of how they interpret situations. For example, currently I’m treating a severely depressed client I’ll call Mary, who basically sits on the couch for most of the day, feeling hopeless and sad. Even though she understands that she’d be better off if she were to become more active, she can’t overcome her profound lethargy. She continually has thoughts like This apartment is so messy. Nothing’s put away. What’s wrong with me? I should get up and do something, but it’ll just be a drop in the bucket. What’s the point? No wonder she feels so depressed and hopeless and just stays on the couch.

The repeated themes in people’s thinking and behavior always make sense once we understand the basic way they view themselves, their world, and other people. Mary, for example, sees herself as helpless and incompetent, a “complete failure,” and that pervades her moment-to-moment experience. Not only does she feel unable to get off the couch, but she also believes that she won’t be able to solve any of her problems and that nothing, including therapy, can help.

That kind of outlook is one of the biggest problems in working with depressed clients. How do you begin trying to work with someone who seems so hopeless?

Beck: First, I reinforced her for being open about her skepticism: “Mary, it’s good you told me that.” Then I reinforced the cognitive model by saying, “That’s an interesting thought. You don’t think that therapy can help. How much do you believe that?” Then I proposed we test the thought: “Mary, I’d like us to figure out whether that thought is likely to be 100 percent true or 0 percent true or someplace in the middle.

Is it okay if we take a look at it?”

I asked Mary several questions. What evidence did she have that the thought was true? What evidence did she have that the thought wasn’t true or not completely true? Was there another way of looking at this situation? What was the effect of telling herself this over and over? If her best friend had this thought, what would she tell her? Following our discussion, I asked Mary what she thought would be important to remember. She verbalized a good summary, which I suggested we should write down: “Just because other therapy didn’t help much in the past doesn’t mean that this therapy won’t. It sounds different, and it makes sense. I would want Joyce [Mary’s best friend] to give it a try. I should do that, too.”

And finally, I asked Mary whether she’d be willing to let me know in the future if she again became skeptical that therapy would help. She agreed.

Is that how you usually handle negative feedback?

Beck: Clients should always be positively reinforced for expressing their doubts and concerns about therapy or the therapist. So the first thing we generally say is something like “It’s good you told me that.” Then we need to understand why the problem arose. If I think I’ve made a mistake, I apologize and figure out with the client what we need to do to address the problem and prevent it in the future. For example, I remember another depressed client, named Lori, who got quite upset one day when I pulled out a Thought Record to help her learn how she could evaluate her own thoughts at home.

“I hate worksheets!” she said. “They never help!”

“I’m sorry,” I said. “I made a mistake. This was obviously the wrong thing to do.”

So I tore the Thought Record in half and threw it away to demonstrate to her that I wanted to make treatment right for her. I also asked, “Would you be willing to let me know the next time I make a mistake?” When she said she was, I asked, “Can we go back for a minute? What do you think of the idea of trying to answer back some of these thoughts we were talking about before that are so upsetting when you’re at home?” She agreed with that idea in principle, and we figured out another way for her to do this without a worksheet.

When a client expresses a distorted cognition about the therapist, a different strategy is needed. Mark, for instance, got annoyed with me when I told him I was sorry that I couldn’t extend our session. He told me that I obviously didn’t care about him. Again, I positively reinforced him for the feedback and told him I was sorry he was feeling annoyed. Then I asked his permission to test this thought. After a brief discussion, he concluded that his view had been in error.

Cognitive therapy is often criticized as not attending to the therapeutic alliance. Yet here it sounds as if you’re addressing it quite directly.

Beck: I’m not sure how this view started, but it certainly isn’t true. The earliest textbooks in cognitive therapy, written over three decades ago, discuss its importance. A strong therapeutic alliance is essential to treatment. It’s just not sufficient in itself to help clients get better as soon as possible. Therapists also need expertise in cognitive conceptualization, treatment planning, and the technical aspects of carrying out treatment.

As a therapist, you always need to adapt your style so it meshes with the client’s preferences. You need to be attuned to changes in the client’s mood during sessions to pick up when he or she is having important automatic thoughts. You need to be highly collaborative and elicit feedback. You need to use all the basic Rogerian counseling skills. In other words, you need to be a nice human being in the room with the client and treat every client the way you’d like to be treated. And of course, therapists need to work on their own negative reactions to clients.

I think part of the misperception people have about cognitive therapy comes from the fact that research studies use manuals. But there’s a huge difference between how cognitive therapy is conducted in randomized controlled trials—which require standardized procedures—and clinical practice, in which it’s crucial to fit the therapy to the client’s cultural and educational background, stage of life, personal preferences, and many other things. Cognitive therapy is definitely not a one-size-fits-all treatment. In fact, therapists who implement treatment in a cold or mechanical way are violating fundamental principles of the cognitive approach.

While cognitive therapy is the most researched therapy model, it still hasn’t achieved widespread acceptance among many clinicians in private practice, who complain that it’s too structured and restrictive. Why so much emphasis on structure?

Beck: First, people who think cognitive therapy is too structured and restrictive have a fundamental misunderstanding about the treatment. They don’t understand that treatment needs to be adapted for the individual. Most depressed clients appreciate the basic structure because it makes sense to them, and they like the idea that we’re going to help them solve their problems, step-by-step, and teach them skills to feel better by the end of each session and, more importantly, during the coming week. When clients express a preference to be less structured, the therapist accommodates their desire, perhaps suggesting that the session be divided into a part that’s less structured and a part that focuses on helping them become more empowered.

Why do we structure the session in the first place? Every minute in a session is precious, and we want to maximize the time we have to help clients learn to deal with the issues that are most important to them. At the beginning of sessions, we do a mood check (so we can make sure that clients are improving), get an update (including a review of their action plan from the previous session), and find out what problem or problems they most want help in solving. Then we help clients prioritize their issues and ask them which one they’d like to start with.

In the middle of sessions, we discuss their most pressing problems and collaboratively decide where to start working. For example, should we do problem-solving? Should we help them evaluate their thinking? Should we teach them emotional-regulation skills, or other cognitive and behavioral techniques? After discussing the problem and working at one or more of these levels, we ask clients, “What do you think would be important for you to remember this week? What do you want to do about this problem this week?” We give them the choice of writing down this important summary or having us write it down for them.

At the end of sessions, we ask clients for feedback. What did they think of the session? Was there anything they thought we didn’t understand? Is there anything they want to do differently next time?

The cognitive approach seems to pay a lot of attention to therapeutic homework. Why is that so important?

Beck: We tell clients that it’s not enough just to talk for 45 to 50 minutes a week in therapy sessions. The way people actually get better is by making small changes in their thinking and behavior every day. Homework is a big part of helping clients learn to be their own therapist. It should be set collaboratively and may include implementing solutions to problems, reviewing responses to key automatic thoughts, evaluating and responding to new automatic thoughts, and practicing behavioral skills.

A follow-up to every session is crucial, but often we don’t call these assignments “homework,” since that term has negative connotations for some people. So we may call them “action plans” or some other term the client wants to use. It’s important that therapists provide a rationale for these assignments, that they set them up collaboratively, and that they be on the easy side. A major reason that clients don’t do homework is because we therapists overestimate what they can do on their own. So when we discuss homework with clients, the most important question is “How likely are you to do this action plan this week?”

If clients say, “90 to 95 percent,” they’ll usually go ahead and do it. But if clients say, “75 percent,” that means, “I’m not really sold on this, and I’ll probably do some of the action plan the night before our session.” If clients say, “about 50-50,” that generally means, “I’m not going to do it.”

So if it’s below 90 percent, I ask, “What’s that 15 percent that thinks you might not do it? What might get in the way?” We need to look for practical problems, such as time constraints, or automatic thoughts, such as Well, I don’t think it’ll really help. To make homework successful, you need to assess the likelihood that the client will do it.

With more difficult cases, we might offer clients the option of calling in and leaving a message for us to say whether or not they were able to do the assignment. In an even more difficult case, we might have a quick phone check-in partway through the week to see how a client is doing.

What do you say to people who dismiss cognitive therapy as too intellectual?

Beck: Again, a fundamental misunderstanding of treatment. Cognitive therapists know that it isn’t sufficient for people to change their cognitions just at the intellectual level. They need to change their thoughts and beliefs at an emotional level as well. So we use lots of experiential techniques, like imagery, behavioral experiments, psychodrama, and role-playing. In fact, we adapt techniques, in the context of the cognitive model, from a range of psychotherapeutic modalities: Gestalt therapy, dialectical behavior therapy, compassion therapy, acceptance and commitment therapy, interpersonal therapy, positive psychology, mindfulness, and—especially when a client has a personality disorder—psychodynamic therapy.

With the rates of relapse for depression being so high, what’s the role of relapse prevention in your work?

Beck: Relapse prevention begins in the first session, when we tell clients that we want to help them become their own therapists. We’re careful not only to use techniques with clients, but also to teach them how to use these techniques themselves, so they’ll have a toolkit for life. As soon as clients begin to feel a little better, we ask them for their attribution. If they attribute progress to medication or to the therapist or to some external person or factor, we might also ask say, “That probably helped, but were there any things you did differently this week or any ways you found yourself thinking differently?” We’re always trying to get clients to give themselves credit and to help them understand their central role in feeling better and making changes. They need to build their sense of self-efficacy so when they face challenges after treatment is over, they’ll have the confidence to tackle them.

Toward the end of treatment, we ask clients to write a list of early warning signals they’ll use to detect if they’re starting to get depressed again. Then we help them develop a written plan of what they should do if that happens. We also teach them how to hold a self-therapy session with themselves. We try to taper sessions so clients gradually end treatment, and if possible, we schedule booster sessions after treatment is over. Overall, the research shows that clients who’ve had cognitive therapy have about half the relapse rate as those who only take medication.

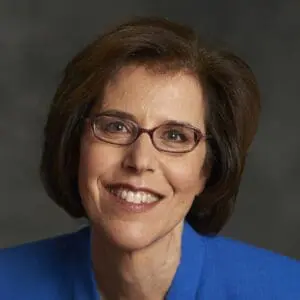

Photo © Filo / Getty Images

Judith Beck

As President of Beck Institute, Judith S. Beck, PhD, provides the vision and leadership to further our mission: to improve lives worldwide through excellence and innovation in Cognitive Behavior Therapy training, practice and research. She is also Clinical Professor of Psychology in Psychiatry at the University of Pennsylvania where she teaches psychiatric residents. She received her doctoral degree from Penn in 1982.