My journey as a therapist began as a counselor in a residential treatment center for emotionally disturbed adolescents in British Columbia, Canada. Overnight I was plunged into doing individual, group, and family therapy with kids who showed up with every problem under the sun, including schizophrenia, homicidal behavior, and anxiety disorders. I had an undergraduate degree in English literature and one year of teacher training. My actual training for helping these kids at the time was exactly zip, nada.

Back then, the human potential movement was in full swing. Encounter groups were the cutting edge, with everyone lining up to beat a cushion with a tennis racket and yell about their mother, thereby releasing their deep inner rage. Gestalt therapy and primal screams were everywhere. For a nice, polite English girl, it was like being thrown in the touchy-feely deep end without a life jacket. And I was lost!

At the treatment center, I was immediately given my own kid to work with, one on one. His first name was Lee, and he had a last name that sounded something like Wimple. I remember that because Bruce the Bulldozer, the reigning Cottage One bully, who terrified kids and staff alike with his graphic physical threats and huge wide shoulders, would stamp around chanting “Wimple, Pimple, Simple” whenever he saw poor Lee. It said something about Bruce’s power that all the staff would do about it was to ask him, politely, whether he might consider stopping this chant. Of course he ignored us.

Lee was about 15, thin and tall, with huge round eyes and a wardrobe of pale button-down, plaid, short-sleeve shirts, which made him almost invisible. His most striking feature was a corrugated helmet of hair that stood straight up on his head in waves, like a young Kramer from Seinfeld.

Also, Lee did not speak, ever. He was silent from sunup to lights-out. And he had a phobia that if he swallowed his saliva, he’d die. So he’d walk around with his cheeks gradually ballooning out, until he’d finally have to dash to the bathroom to empty out his mouth. Lee’s mom had died when he was small, and he’d been brought up by his much older father on an isolated farm, missing school and finally being apprehended by social welfare workers. Despite my grand title of chief therapist, I had absolutely no idea what to do with him.

In family sessions, Lee stared at the floor while his dad sat with his back to his son and droned on to me about the farm and how Lee wasn’t much help to him there. There seemed to be no connection between father and son. In group, Lee would react to questions by widening his eyes and staring frozen into space or moving his head down like he was about to dive head first into the carpet. This would invariably trigger Bulldozer Bruce to unleash the “Wimple, Pimple, Simple” chant, plus a few more particularly virulent expletives.

But the individual sessions with Lee were the real challenge for me. Despite all my best efforts at empathy, insight, and problem solving, all I could get in response to my questions and suggestions was his wide-eyed stare. That was it. We were stuck. I can do conflict, I thought, but this is too hard. Maybe I should go into law. Maybe therapy only works in California, where folks like self-disclosure. How can you do catharsis with The Silent One?

One day, after noticing that Lee had books of birds in his room, I suggested that we sit in the garden for our sessions. He nodded agreement and sat silently while I singlehandedly carried on with “therapy.” I was too green to realize that putting words in a client’s mouth was no-no, so I went on about how hard it must be to be a kid, all alone in the world, not able to trust anyone, not feeling safe even within my own body. I went on about how poisonous all the taunting and being left out must feel to him, and how if I were in his place, I wouldn’t be able to swallow that. “I think I’d put a big wall of silence around me and just watch for danger,” I told him.

As I tried to tune into his world and put words to his experience, he occasionally gave me a slight nod. Sometimes I’d tell him stories from my own past, when I was bullied because my accent was too working class. I told him that my response was to become enraged and even mean, and that I thought that his way of silence was probably a better reaction. Still, my sessions with Lee felt very long, and the weeks went by very slowly.

After about two months, however, I noticed that he began sitting just a little closer to me. One afternoon, when I saw his cheeks start to fill with saliva, I touched him gently on the arm and suggested that he try to swallow, and if anything happened, I’d be there with him. He did.

Soon, when I began talking to him about the birds we saw in the garden, meticulously written fact sheets started turning up on my desk about grackles and rufous-sided towhees. My supervisor said Lee wasn’t making any progress, but he’d started swallowing when I’d touch him on the arm at various times during the day. And when Bruce the Bulldozer began his tirades against him, Lee began came to stand beside me.

Then came the day when Bruce went out and bought himself an expensive pair of white, pointy cowboy boots. For days, he proudly pranced around the cottage showing off those boots. But one morning, he stormed into the cottage group meeting enraged. “Someone has wrecked my boots!” he screamed. “They’re ruined! I’ll kill whoever did this. I’ll kill them!”

Everyone carefully stared at the floor as Bruce raged and ranted. But when I looked over at Lee, I noticed he had a little grin on his face; and when I grinned back at him, it broke into a huge smile. Suddenly, Lee stood up and flapping his hands like he was revving himself up, he opened his arms wide, threw them high into the air, and announced triumphantly to me, and to everyone in the room, “I peed in his boots! I peed in his boots!”

There was utter silence. Nobody moved. Then I started to laugh—I just couldn’t help it—and suddenly we were all roaring as Lee stood tall, grinning, looking infinitely pleased with himself. Bruce the Bulldozer was thunderstruck; he looked confused, and then he fled.

Lee changed after that: defiant urination could definitely be considered the treatment of choice in his case. He started to talk to me, albeit in long, stilted sentences. He made a friend in the group. We found him a foster family, and he told his dad he wasn’t coming back to the farm. Finally, he left the cottage. I never found out what happened to him after that, but I know he stopped being afraid to swallow—and that he found his voice.

It would take a little longer for me to find my voice as a therapist, but I learned so much from Lee. That skinny boy with the big eyes taught me how to simply stay with a client and accept where he is—how to feel into and respond to another’s pain, and help him make sense of it. I learned that therapy is a dance, and just as in a dance, the magic is not in the steps, or the tricks, techniques, or flashy moves. It’s in the togetherness, in the belonging that leads to becoming. Lee taught me that therapy is about attunement, attunement, attunement. This coming together changes both client and therapist! And I use what Lee taught me in every session.

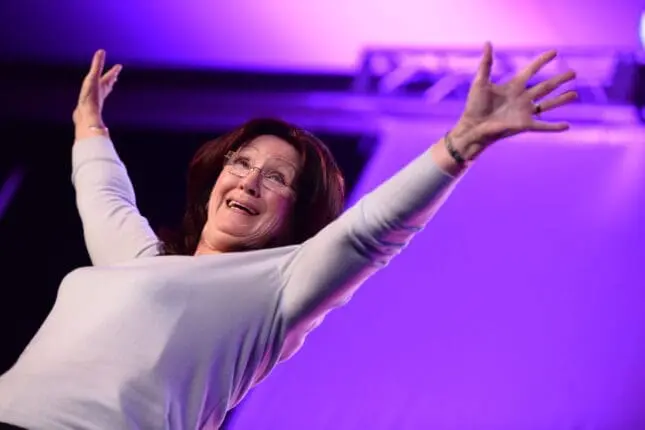

Watch Sue’s full talk from the Symposium.

Photo by Sam Levitan

Susan Johnson

Dr. Sue Johnson was the primary developer of Emotionally Focused Couples and Family Therapy (EFT), which has demonstrated its effectiveness in more than 30 years of peer-reviewed clinical research. Her books include Attachment Theory in Practice: EFT with Individuals, Couples and Families (2019) The Practice of Emotionally Focused Couple Therapy: Creating Connection (3rd edition, 2019) and Emotionally Focused Couple Therapy with Trauma Survivors (2002). Read our tribute to Sue and learn more about her legacy on her website.