Two middle-aged men, who appear to be only glancingly familiar with each other, are up on a stage about to do something that’s both an inescapable part of everyday human experience and a doorway to the deepest form of intimacy—tapping into the power of body-to-body communication.

TJ is a soft-spoken movie-industry career man, sitting ramrod straight against an upright pillow in an armchair. Wearing a plain blue sweatshirt, dark slacks, and hiking shoes, he looks slacker-casual, but he’s clearly anxious, staring wide-eyed at the man next to him as he waits to be told what to do.

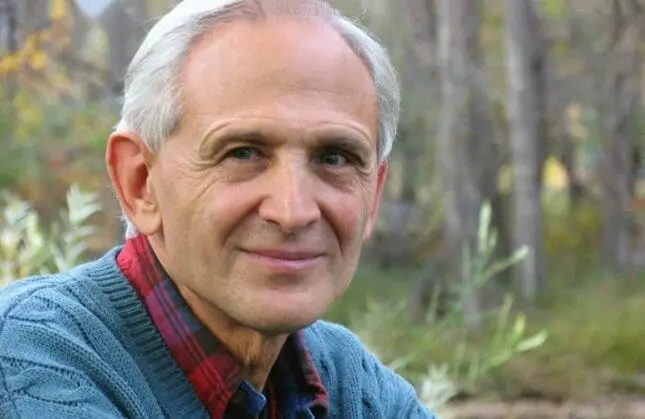

That man he’s deferring to is Peter Levine, the originator of a form of body psychotherapy called Somatic Experiencing (SE). Levine’s thin frame and clean-cut, tidily dressed look give him the appearance of a museum docent, rather than a man who’s leading a small legion of practitioners to refine and harness their intuition as they direct their attention to the body. With his shock of white hair, kindly avuncular eyes, and the calm way he’s nestled into his chair, we get the sense that TJ, whom he’s brought up on stage for a demonstration of SE, is in good hands.

Levine starts by asking TJ why he’s come, and TJ haltingly describes how years ago, he started waking up with a painfully tight back each morning. Despite doctors, acupuncturists, chiropractors, massage, and staying active for many years, the pain just worsened over time. As TJ finishes his description, Levine, who’s been leaning back in his chair with his hands near his hips, readjusts the distance between his feet to mirror TJ’s. He brings his hands together and entwines his fingers just as TJ has done. He nods repeatedly as TJ winds down the presentation of his issues, continuing even after TJ has finished.

If these two were young brothers, TJ might take this moment to snap at Levine: “Stop copying me!” But there’s a method to all the shifting around Levine is doing. He’s attempting to enhance his nonverbal, body-to-body communication with TJ, what in SE is called achieving “resonance” between the therapist and the client.

Instead of asking questions about events that might have first elicited TJ’s pain, or even about his current emotional state, Levine focuses on the body, zeroing in meticulously on what’s happening in the moment. He tells TJ that he’d noticed him end his explanation with an almost imperceptible movement—a very slight lifting and dropping of his feet and arms—and says the movement suggests his readiness to take real action to tackle his pain.

It’s the sort of observation that could make a talk therapist wonder to herself, C’mon, nothing significant happened. Even if he did move a bit, isn’t it a stretch to read intention into such a tiny movement? But to Levine, minute shifts in breathing patterns or physical gestures are a big deal. Also, he’s seeing something the untrained observer likely hasn’t noticed. As he’ll tell trainees later, TJ’s color changed while he talked, and Levine divined that his pulse picked up. This belied TJ’s “restricted and still” posture, Levine says, and showed him that TJ’s autonomic nervous system was readying him to finally take action and do something different to relieve his pain. Where most of us would’ve seen nothing, Levine ferreted out a signal. As he says, “the body is trying to tell the story” behind TJ’s pain in its own way.

Back on stage, TJ seems to get this. When Levine says he’s seen TJ’s body communicate a need to, “get going” and “do something about it,” TJ readily agrees. “I’m kind of wired that way,” he says. Levine asks him to stay with the feeling and introduces the image of a horse that’s straining against his reins to run free through a meadow. TJ interrupts Levine’s description and, quietly sniffling, blurts out, “That’s the way I feel.”

Levine quiets at this and begins to nod again while looking into TJ’s tearing eyes. It’s hard not to notice that they’re about two minutes into their interaction, and something emotionally powerful has already begun to unfold. Still holding TJ’s gaze, Levine says, “Uh-huh,” and “Mmmm,” though TJ hasn’t said a word. Then, after 20 seconds of silence passes, hanging awkwardly in the air between them, suddenly, Levine offers a seemingly out-of-nowhere direction: “And feel the breath.”

“Yep,” TJ says, laughing shyly at first, as if acknowledging some secret message about breathing Levine had already sent his way. Then he loudly exhales as he continues to tear up. Levine asks TJ to focus on his body’s messages by going back and forth between an image of the horse running freely and whatever sensations or feelings are arising in his body in response.

When TJ reports a vague yearning, and a “lightening of the mind,” there’s more silence, but rather than feeling empty, it’s as if the two are now in their own private mind meld. After Levine gently invites him to explore how it feels to cry, TJ tells a tale of running to his mother as a young child after a friend had knocked him down in the street. Instead of comforting him, he says his mother told him to stand up for himself and fight back. Now the tears are coming faster, and TJ needs a tissue. After recalling this memory—and presumably the lasting message it gave him to redirect emotional hurt outward—TJ tells Levine he’s just felt some pain release in his back.

Later, Levine will offer TJ his wrist to grasp, and ask him to empty his tension into it—an exercise that TJ says also causes something to shift inside. By the end of this session, filled with wordless moments, TJ tells Levine it’s worked—the pain that’s been his constant companion for many years has released its grip on him.

Watching this play out is captivating, but also puzzling. There’s been no big dramatic moment or cathartic release. TJ says he’s better, but is he really? Has he just fallen under the spell of a transient effect brought on by the bright lights of the stage and the heightened expectations of those watching? How long will it last? It seems whatever has happened remains beyond the reach of words, or at least easy explanations.

This notion isn’t helped by the fact that Levine has spent little time using the familiar languages of psychotherapy in favor of the subtle and mysterious language of the body and its sensations, a language few of us have been trained to understand. Was he guided by some therapeutic master plan, or just his moment-to-moment intuitions? Why did he make the choices he did? Levine is clearly practiced at what he does, but at the end of his session with TJ, we’re still left asking, who is this guy, really? And what is he doing? And why, with all the other ways we have to work with trauma, is his approach suddenly such a big deal to practitioners, who are clamoring for his trainings?

Including the Body

Whatever you think about body psychotherapy and those considered masters of it, like Peter Levine, there’s no denying that today it’s achieved a once-unimaginable place of acceptance in the wider field of psychotherapy. Indeed, Levine and other body therapists have worked hard for decades to overcome skepticism about the value of somatic methods that began long ago in reaction to Wilhelm Reich, a one-time deputy director of Freud’s outpatient clinic, who emphasized Freud’s view of unconscious drives and brought his own highly controversial approach to engaging the body in the therapy room.

Reich, before he died in a Pennsylvania prison while doing time for mail fraud, was an early proponent of the idea that our musculature and body postures were shaped by the unexpressed emotional residue of traumas—a belief, by the way, that’s since become an integral part of today’s trauma work. But Reich took work with untapped bodily and sexual energies to extremes that trampled professional boundaries. To break through the psycho-emotional armor of their bodies, he periodically asked clients to undress, sometimes fully, so he could vigorously massage them. He explained that repressed memories from childhood could be retrieved this way, but he also sometimes set having orgasms in sessions as a goal.

Reich had a tumultuous personal history, including a sexually precocious childhood, a mother who killed herself after Reich had told his father about her affair with his tutor, and a history of affairs with his patients, one of whom died in a room she’d rented for their clandestine meetings. He was also widely pilloried for inventing the so-called “orgone accumulator,” an insulated box about the size of a Port-a-Potty that he claimed could accumulate free-floating sexual and cosmic energy and even potentially cure cancer for the person sitting inside. Years later, he achieved a kind of dubious postmortem popularity when orgone-like vessels were included for comic effect in the films Barbarella and Woody Allen’s Sleeper.

Despite the controversy, Reich had his defenders—especially in the United States, where he moved before World War II—who were taken with the cathartic intensity of his approach and his almost mystical claims of being able to release “blocked energy.” In fact, bioenergetic therapy, which promotes cathartic physical and emotional release through touch and movements like kicking and pounding, was started by two students of his, Alexander Lowen and John Pierrakos, and is still practiced today. Nevertheless, thanks to Reich’s controversial methods, many body-oriented therapies that sprang up after him got off to a rough start. Even now, something odd and disreputable lingers over mind–body approaches that seek to offer clients cathartic release.

Professional ethics aside, however, Reich’s emphasis on the role of the body in our emotional lives, after many years at the periphery of clinical practice, has moved into the psychotherapy mainstream. Most therapists these days recognize that the body holds onto pain or fear. Most are familiar with how traumatized clients often present with somatic complaints, and with how a lack of touch can frustrate primal needs for connection. Modern therapists who ignore the body in practice are now, more than ever, challenged by the increasing acceptance of the idea that purely verbal approaches are insufficient to address the full impact of trauma.

A big leap forward for somatic approaches came in the ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s, with the publication of bestselling books like The Relaxation Response by Harvard doctor Herbert Benson, The Relaxation and Stress Reduction Workbook by Kaiser Permanente’s Martha Davis, and The Complete Illustrated Book of Yoga by Swami Vishnudevananda, all of which touted the benefits of engaging the breath and calming the body.

As interest in relaxation, meditation, and yoga entered into an even wider cultural consciousness, the taboos about integrating clients’ physical self into therapy were slowly chipped away, challenging the belief that focusing too much attention on the body might scare clients off and muddle the therapy process. The work of innovators like Moishe Feldenkrais, Ilana Rubenfeld, and Al Pesso developed somatic approaches that gave body-based approaches further visibility.

Perhaps the most influential figure in educating the general public about the mind-body connection was Jon Kabat-Zinn, a professor at the University of Massachusetts Medical School, who’d studied with Thich Nhat Hanh and other Buddhist teachers. Downplaying their spiritual dimension, Kabat-Zinn couched the benefits of mindfulness and meditation in scientific terms and brought a secular perspective to the use of Eastern mind-body practices. His appearance on Bill Moyers’ wildly popular documentary Healing and the Mind, and the development of his eight-week mindfulness-based stress reduction course, were milestones in taking what were once considered mysterious practices into the cultural mainstream.

Meanwhile, developments in brain science and the advent of imaging techniques were making it clear how “embodied” the mind is. Contributors like Daniel Siegel and Alan Schore began introducing therapists to the clinical relevance of and interconnection among brain development, healthy attachment, and the biology of the human nervous system. The study of what Siegel called interpersonal neurobiology gave therapists a new perspective on the way our most important relationships fire into being the neural circuits of the brain that allow us to understand and empathize with others and feel their feelings. It became increasingly clear that brain and body were not only unquestionably connected, but working together to process emotion and cognition, and responsible for the miracle of human consciousness.

But the most direct therapeutic application of the mind–body connection has come from the field of trauma treatment. As Bessel van der Kolk, author of the bestselling book The Body Keeps the Score and one of the prime movers in establishing the scientific foundations of body-based therapy has put it, the imprint of the trauma doesn’t sit in the verbal understanding of the brain but lies in much deeper regions—amygdala, hippocampus, hypothalamus, brain stem—which are only marginally affected by thinking and cognition. People process their trauma from the bottom up—body to mind—not top down. For therapy to be effective, we need to do things that change the way people regulate these core functions, which doesn’t usually occur through words and language alone.

Arguably, over the past two decades, the advent of bottom-up psychotherapy—fueled by a range of clinical, scientific, and cultural developments—has been the most influential movement in the field of psychotherapy to date.

The Somatic Experience

Peter Levine and Somatic Experiencing, the approach he developed, have been at the forefront of this movement, but it hasn’t been an easy ride. Early on, when people stumbled into his workshops and saw how he was asking clients to explore the inner world of body sensations, many would get up and leave. He has a theory about this initial resistance to his work. “We live in a very touch-deprived environment,” he says. “So talking about intimacy with the body was very threatening at the time.”

Today, no body-based therapy has gained more proponents than Levine’s. His first book about Somatic Experiencing, Waking the Tiger: Healing Trauma, has gone on to sell a quarter of a million copies. At present, more than 12,000 people on six continents have been trained in SE, and there’s even been a randomized control study that supports its claim to effectiveness with PTSD. While informed by Reichian concepts that the body holds emotion and trauma that needs to be attended to and released, SE’s techniques are designed to be subtler and quieter, not unlike the man who originated them.

Levine comes across as the most un-Reichian of body-oriented therapists. He has degrees in medical and biological physics, as well as psychology, and he once worked for NASA, de-stressing the staff during the development of the space-shuttle project. Among the most enthusiastic proponents of his approach is van der Kolk, who shares Levine’s belief that trauma is not only the deeply upsetting experience itself, but “the imprint left by that experience on the mind, brain, and body.” He appreciates that Levine uses the sort of bottom-up methods that incorporate the body and allow clients to “have experiences that deeply and viscerally contradict the helplessness, rage, or collapse that result from trauma.”

Rather than seeking some sort of physical catharsis with clients, Levine proceeds more gradually, helping them first adjust to accessing their trauma-related body sensations by using methods like what he calls pendulation, the gentle shifting of focus between disturbing sensations and feelings, and positive memories and body states. This exploration of the somatic residue of trauma doesn’t require prolonged immersion in dysregulated states or a focus on traumatic memory itself. His goal is to help clients, little by little, find new ways to regulate themselves, as they find both physical and emotional release.

“One thing that SE teaches therapists is that when you’re working with trauma, pacing matters,” says Eduardo Cortina, a therapist in the DC metro area, who got certified in SE because he wanted a way to safely address the trauma in clients who’d been coming to him for bodywork. “You first want them to notice their bodies and integrate them into therapy. So you want to challenge the nervous system, but not overwhelm it. A central concept in SE is titration, which in some ways resembles tai chi. The idea is that less is more, and it’s important not to rush as you help people gain capacity to deal with deeply upsetting experiences.”

So how do you train therapists who’ve relied on talk as their primary clinical tool to shift into body-based approaches? Watching Levine work raises the question of whether he relies more on his keen attunement to the subtleties of body language and practiced ability to enhance his clients’ somatic awareness, rather than on any therapeutic road map he can relay to the rest of us. Levine insists that talk therapists, many of whom can be as disconnected from their bodies as their clients, need first to trust their own bodies and study their own sensations if they ever hope to be adept at this kind of work. They need to align with the client on a deep level, to the point that their own sensations will shift along with a client’s.

Even therapists who approach trauma from different directions are drawn to Levine’s approach. Trauma therapist Deany Laliotis, head of training for the EMDR Institute, who has taken his training, says, “I wanted to learn more about SE because I was struck by the amount of body processing in my EMDR sessions, and realized I was out of my depth.” The experience has added another dimension to her work. “Since the training, without being consciously aware of it, I’ll often find myself sitting in a similar stance to a client’s in sessions—even if it’s a big guy with his legs spread—and talking in a similar tone. Our bodies are then talking to each other. It’s become a natural part of how I work.”

At a time in which online counseling and mental health apps seem to be offering clients a therapy experience shaped entirely by disembodied talk, a slower, older movement grounded in the body is gathering steam of its own. It’s calling therapists and clients to go beyond their lonely keyboards and tune in to the expanses of innate bodily wisdom. And for Levine, now acknowledged as one of the most respected pioneers in a form of therapy once considered taboo, one can imagine that a benefit of his life’s work is that it allows him to feel the field’s newfound embrace very deeply inside him.

Lauren Dockett

Lauren Dockett, MS, is the senior writer at Psychotherapy Networker. A longtime journalist, journalism lecturer, and book and magazine editor, she’s also a former caseworker taken with the complexity of mental health, who finds the ongoing evolution of the therapy field and its broadening reach an engrossing story. Prior to the Networker, she contributed to many outlets, including The Washington Post, NPR, and Salon. Her books include Facing 30, Sex Talk, and The Deepest Blue. Visit her website at laurendockett.com.