Enjoy the audio preview version of this article—perfect for listening on the go.

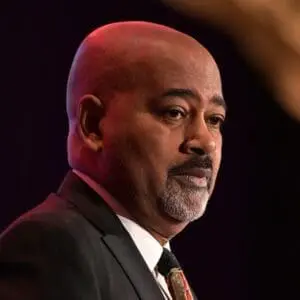

For someone who’s about to lead a clinical workshop on racial reactivity and defensiveness, Ken Hardy looks remarkably unreactive, at ease even. Then again, he’s been presenting various permutations of the topic at the Psychotherapy Networker Symposium for nearly three decades.

In the past, these kinds of discussions about race and therapy haven’t always gone smoothly. Plenty of therapists—who are usually good communicators with advanced emotion-regulation skills—have raised their voices, sobbed into microphones, and even stood up and stormed out of the room. This year, the workshop unfolds against a political backdrop that includes a slew of executive orders promoting racial profiling and unlawful deportation, new policies criminalizing practices related to DEI, and landmarks being removed and renamed in ways that erase the history of Black Americans and other marginalized groups.

Yet Hardy is undeterred. In his role as supervisor, professor, and author of books like The Enduring, Invisible, and Ubiquitous Centrality of Whiteness and On Becoming a Racially Sensitive Therapist, he doesn’t just teach about racial reactivity and defensiveness, he actually welcomes it into the room. The tensions and intensity that arise allow for honest discussions with real feelings, which Hardy then folds into clinical concepts and tools, offering an antidote to our culture’s entrenched habit of avoidance and self-righteousness.

When Hardy first started giving a version of this workshop in the early ’90s, nearly all the participants were people of color, in part because it was the only training that even touched on their concerns and challenges around race in the therapy room. But it was also a respite—one of the few spaces where Black therapists in a predominantly white field could let down their guard. Today, it’s not just the racial makeup of participants that’s different—there are plenty of white clinicians in the room. The conversation itself has evolved. Racial reactivity used to be thought of as the rapid, inevitable escalation of anger and frustration, now we see it in a more nuanced way: as a complicated slow-burn of disengagement, defensiveness, and hopelessness.

“As you can tell,” a Black man in the front row says to Hardy when he invites audience members to express their version of racial reactivity today, “I’m not a shrinking violet. I’m 6-foot-1 and 200 pounds. When I walk into a room, I take up space. I do this from the most authentic place I can. But as Ta-Nehisi-Coates says, when simply being in my skin is perceived as threatening, I don’t have much control over what happens to my body. I know it’s my job to be aware of my own privilege as a highly educated person and a man, but I feel like that privilege sometimes puts an even bigger target on my chest.”

Several white therapists admit to trying to be “the good white person” in conversations about race, a self-protective stance Hardy says makes it difficult to move the needle. “When we as white people try so hard to be nice,” an older man adds, “that’s a stress response. We’re fawning. We’re coming from a place of fear. We’re defending ourselves rather than showing humility and openness.”

A white woman discloses, in a trembling voice, her feelings of heartache and regret about an interaction she had with a client of color she’d worked with for several years. The client had made a last-minute request to switch his session from in-person to virtual. When he’d appeared on the telehealth screen, he was slurring his words. “In the past, we’d touched on his alcohol use, but this was the first time he’d shown up drunk to a session,” she said. “We chatted for a minute or two, and then I just named the alcohol issue and said, ‘Maybe we should wrap up for today and reschedule.’ So we did. But the next morning, he sent me an email accusing me of being a ‘Karen.’ I wrote him back that I knew talking about this stuff was hard and I was here if he wanted to talk more, but he never contacted me again. After listening to you today, I’m wondering if I missed something important.”

Hardy’s response to hearing this story is to lean into VCR, which isn’t a throwback to ’90s movie nights, but an evolved clinical tool: validate, challenge, and request. It’s a model Hardy has created to help people stay constructively engaged through tough conversations where there’s high reactivity. Using VCR as a technique first requires assuming a particular worldview, though, one where the goal is to embrace complexity and resist the temptation of succumbing to reductionistic, either/or thinking. Given that a Karen has come to mean someone who’s quick to act with little data and lots of prejudicial judgement—usually based on racial stereotyping—the client’s reference to his therapist as a Karen was unquestionably a racial one.

Had the therapist been more practiced in adhering to a VCR worldview in this kind of high-stakes clinical situation, she might’ve thought to validate the client’s commitment to showing up for sessions, which could’ve included an acknowledgement of how he’s courageously defying the stereotype of Black men shying away from the challenging, vulnerable work of therapy. This acknowledgement, had it come before her comment about his intoxication, would likely have elicited a different response from him—one that was less reactive. Without it, the therapist became just another white person judging him in ways he interpreted as having racial—and possibly racist—underpinnings.

“Before you challenge, confront, critique, or correct,” Hardy says to her, “you find something to validate. We tend to skip this step. But it’s important to find the value in what another person is doing or saying before we challenge them. This is even more critical in interracial conversations because we live in a context of so much historical racial strain and harm. So I appreciate you for sharing your story. That’s a very difficult situation to be in, and you made a game-time decision. You were correct to name his impaired state during that teletherapy session, but I believe you missed a few critical, preliminary steps in the process.”

“Beginning with the validation part,” the woman in the audience murmurs into the mic regretfully. “I could’ve noticed something good about what he was doing first.”

“Once we validate,” Hardy affirms, “we can then move to the ‘C’ of VCR—challenge—which we always start with an and rather than a but, because you’re trying to hold complexity. That’s where we engage the other person in compassionate accountability. With this client, that might have sounded like ‘I really appreciate that you showed up today, and I’m worried that we won’t get the full benefit of our session time.’ Then we could have gotten to the ‘R,’ which is a request that we’re making of the other person. Your request, ‘How do you feel about us wrapping up for today and rescheduling?’ might have been experienced differently by your client had the other two steps preceded it.”

Hardy believes that when we’re willing to apply this to conversations around race—however haltingly and imperfectly—it can serve as an antidote to the reactive-defensive loop where all we’re doing is reinforcing old narratives and piling new harms onto old ones. He sees our culture’s perverse relationship with race as arising from the fact that the significance of race is regularly denied and dismissed, even though it organizes nearly everything we do, from where kids sit in cafeterias to the legacy of Jim Crow embedded in our legal, carceral, educational, and medical systems.

A white therapist in the audience asks Hardy what racial healing actually looks like. “I’ll give you the short answer,” he responds. “I don’t believe true healing can take place in a context of continual assault. It’s like saying, I’m going to create a space for you to heal in our abusive relationship, but I’m also going to keep beating you up. At the same time, I think we can find ourselves on a path toward healing, which then becomes an ongoing process.”

In Hardy’s view, racial reactivity is the outward manifestation of an inward event—one that often goes unrecognized. No matter what our race, we’re a constellation of privileged and subjugated selves. When we’re feeling reactive, it’s because one or more of our subjugated selves is experiencing a threat, and if we’re unaware of what’s happening, we can easily tip into self-righteousness. An added complexity lies in the fact that this threat can be multifaceted and experienced in one or more of four domains: as a threat to our identity, to our autonomy, to our dignity, or to our safety, security, and survival.

“Every one of us has a preferred racial self and a disavowed racial self,” Hardy says. “It’s important to notice which self our reactivity is rooted in.” He shares a story about a white woman at a university who stood up halfway through one of his talks and yelled, “How dare you talk about white people being privileged! I’m white, and I grew up dirt-poor!” This woman didn’t recognize that she had multiple selves, including a privileged white self and a subjugated poor self.

“I looked for a pearl of functionality, for a pearl of worthiness embedded in her comment, and I validated her experience as a woman who grew up poor,” Hardy says. “I applauded her for remaining present in the conversation even though she was hearing characterizations that seemed contrary to her personal experiences and circumstances. I said, ‘It makes perfectly good sense to me that the gravity of the poverty you experienced would make it impossible to think of yourself as privileged.’ I also assured her that based on class status, she was indeed anything but privileged. However, after validating her, I went on to challenge her by saying that in terms of race, being white was a privileged position. While all poor people suffer in our society, it’s a fact that those who are white and poor tend to make out better than those who are poor and racially subjugated. ‘What I’m suggesting,’ I told her, ‘is that you’ve been hurt and subjugated as someone who grew up poor, while at the same time holding privilege as a result of being white. I think your experience of growing up poor has the potential to help you be particularly good at understanding the plight of people of color because you, too, have experienced marginalization. I also hope that every person of color here can relate to the devaluation and degradation you experienced as someone who grew up poor.’”

“When I hear this story, and how you handled it,” a Black man in the audience says, “it feels like you’re asking me to level up even though I’m being beaten down. Frankly, I’m tired of that!”

“Your comment makes sense,” Hardy responds with genuine warmth in his voice. “And I want to point out that what you did just now is exactly what I’m recommending here. You had an emotional response to the anecdote I just shared. But you recognized your response, and you verbalized it. That’s what we all need to do more of. Because if that doesn’t happen, the emotional response turns into reactivity. And I respect what you said about feeling like I’m asking you to level up. For me, though, it’s not about being the bigger person. It’s about accessing your personal power, so others’ inhumanity doesn’t rub off on you. It’s about being the captain of your own ship, the author of your own story. Especially if you’ve been silenced, whether you’re a person of color or a woman or someone who grew up with a tyrannical parent, the simple act of exercising your voice constructively and powerfully is critical. Maybe it changes a social condition, maybe it doesn’t. But there’s a deeper purpose to using our voice. I want us to speak because there are just certain things our ears need to hear our mouth say for the liberation of our soul.”

“Amen!” a Black woman in her 50s calls out. A workshop volunteer passes her the mic, and she rises out of her chair. She doesn’t speak immediately; instead, she glances around the room. Then, she faces the stage. “I needed to hear what you’re saying about multiple selves. I’ve had a lot of painful experiences like what people have been talking about here, but I’m saying amen because I want you to keep preaching and teaching. And I want all of us to keep talking, interacting, and paying attention.”

Hardy nods. For a moment, it’s as though everyone in the room has been lifted up on a swell of collective emotion.

As the end of the workshop approaches, a white man shares a painful experience he had on a therapist listserv after the murder of George Floyd: the online interactions between therapists of color and white therapists got so heated and combative that the administrators decided to pull the plug, ending all communication.

“To me, that’s the worst-case scenario,” Hardy weighs in sadly. “When we go silent. That breeds hopelessness—and hopelessness is contagious. But hope is also contagious.”

Hope can come from different places. For Hardy, it begins with recognizing our personal power. Even when we don’t have what he calls “positional power,” the way—for example—a president of a country does, we’re still powerful. Hardy shares that he sometimes tells his clients and supervisees, “Try to spend more time defining yourself and less time defending yourself. I’m not saying don’t get angry. I’m saying direct and guide your anger to your advantage. Because when you’re defending yourself, someone else is controlling you. But when you’re defining yourself, you’re exercising personal power.”

Alicia Muñoz

Alicia Muñoz, LPC, is a certified couples therapist, and author of several books, including “Stop Overthinking Your Relationship” and “A Year of Us.” Over the past 18 years, she’s provided individual, group, and couples therapy in clinical settings, including Bellevue Hospital in New York, NY. Muñoz currently works as a senior writer at Psychotherapy Networker. Her latest book is “Happy Family: Transform Your Time Together in 15 Minutes a Day.“

Kenneth V. Hardy

Kenneth V. Hardy, PhD, is President of the Eikenberg Academy for Social Justice and Clinical and Organizational Consultant for the Eikenberg Institute for Relationships in NYC, as well as a former Professor of Family Therapy at both Syracuse University, NY, and Drexel University, PA. He’s also the author of Racial Trauma: Clinical Strategies and Techniques for Healing Invisible Wounds, and The Enduring, Invisible, and Ubiquitous Centrality of Whiteness, and editor of On Becoming a Racially Sensitive Therapist: Race and Clinical Practice.