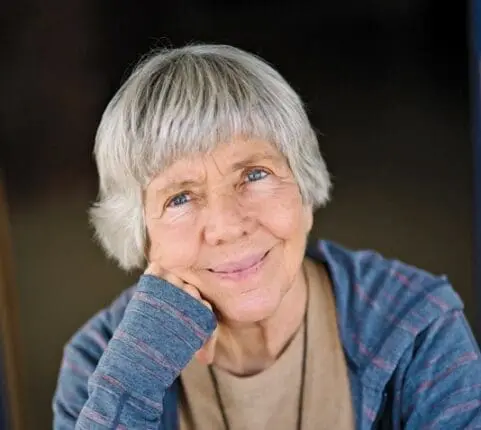

In 1994, after being rejected by 13 publishers, Mary Pipher’s Reviving Ophelia finally appeared. Written with an anthropologist’s eye and ear, it was filled with vivid stories of her teenage clients and their struggles to move toward adulthood in what she called a “girl-poisoning junk culture.” The book gave voice to a cultural undercurrent no one had evoked so powerfully before. Without advance publicity, it spent 26 weeks atop the New York Times bestseller list. Since then, Pipher has written nine other books that have continued to explore the way the wider culture profoundly influences what happens in the therapy room. This year, she celebrates the release of the 25th-anniversary edition of Reviving Ophelia, which she coauthored with her daughter, Sara Gilliam. (A new chapter is excerpted in this issue.)

Psychotherapy Networker: How do you understand the overwhelming response Reviving Ophelia received when it was first published in 1994?

Mary Pipher: My book and Carol Gilligan’s In a Different Voice came out at almost the same time. Until then, almost all the important theorists in psychology were men, which I think was one of the reasons there were so many blind spots in understanding teenage girls. Those books, written by women, got attention because they were looking at teenage girls in a way that hadn’t been considered before.

PN: What were you seeing that inspired you to write the book?

Pipher: It came from my being swamped in my practice with bright girls from intact families who were nevertheless engaging in all kinds of self-destructive behaviors: binge drinking, drugs, casual sex, staying out all night. As a therapist, I’d been taught that there was an explanation for all that—the “dysfunctional family.” But the families I saw didn’t seem especially dysfunctional to me.

PN: So what did the psychotherapy field tell you about how to work with the girls you were seeing?

Pipher: I’d been trained as a family therapist to look for dysfunctionality. Was there a strong parental hierarchy? How did the parents get along? Was the IP, “identified patient,” masking other family problems? But what I kept seeing was that the problems families were having was a symptom of something going on in the larger culture. Teenagers were angry because they felt that their parents hadn’t prepared them to face the complicated new world they were trying to navigate, a world their parents didn’t seem to understand. So on one hand, they felt guilty because they knew how far they were moving away from what their parents wanted for them, but on the other hand, they were angry because their parents weren’t offering useful guidance.

PN: At the time, you were the mother of a teenager yourself. How did what you’re describing play out in your own family?

Pipher: I was dealing with pretty much the same issues as the families in my practice. I figured out that my daughter, Sara, seemed happier on weekends when she wasn’t in school. But during the week, even if she woke up in a good mood, by the time she got home from school, she was grumpy. So in spite of what my family therapy training had taught me, I started thinking that maybe what was happening at home wasn’t the primary source of her grumpiness. In school, she was dealing with all kinds of pressures that weren’t the same as the ones I’d experienced at her age.

Eventually, I realized that all this anger directed primarily at me was about two things. One, I was supposed to keep her safe, but she didn’t feel safe. Two, I was the only person she trusted enough to give a hard time to. She knew that even if she was really angry and sullen with me, I’d hang in there with her.

I saw this with my clients, too: they were ambivalent about wanting to be connected to their mothers, but at the same time they wanted to express all these complicated feelings to them. And the mothers were just beside themselves with worry. Part of the larger cultural problem was that girls needed the connection, but they were getting all this pressure to distance.

PN: So how did your understanding of the culture of adolescence get translated into what you said and did in your practice?

Pipher: One shift I made was focusing more on the lives of the teenage girls outside of their family. I started asking them to talk to me about the movies they were seeing, the music they were listening to, what their school days were like. I’d never directly ask things like, “Are you having sex?” But I’d say things like, “Are the girls you know having sex? And how’s that working out for them? Do you know any girls who’ve been sexually assaulted? How often are you going out with kids who get drunk?” Talking about other girls, they’d get more comfortable.

We also started talking about what it was like to be buffeted around in a sexist and lookist culture. I helped them look at their world with the eyes of an anthropologist. And we worked together to build the inner architecture they needed to respond to this culture. I did “North Star” work with them, meaning I tried to help them find ways to distinguish thinking from feelings, to manage their stress and to be more intentional in their choices.

PN: Give me a picture of how you wove the understanding of culture into your therapy.

Pipher: An example might be working with a girl who came in angry that her mother wouldn’t buy her a particular tennis outfit. The more I worked with families, the better I got at not even messing with that surface stuff. For a girl who’s really upset that her parents won’t buy her a special tennis outfit, the real issues are probably Can I walk onto a tennis court and look like other girls? And what does it mean if I can’t? And how is my self-esteem tied up in all this? Of course, once you figure out that deep structure stuff, you’ve still got a long way to go. But if you sit around talking about a tennis outfit, you’re just wasting everybody’s time.

One of the ways I started moving into a deeper conversation was to tell clients some personal stories about the experiences I had with my own mother when I was a teenager. And instead of figuring out what had happened in their past, I’d talk about the future. I’d ask them where they wanted to travel, what they wanted to be in their career. I’d ask if they wanted to live in a city when they grew up—anything that involved perspective taking and helped them realize that being in seventh grade wasn’t the only thing that would ever happen.

PN: What’s the biggest difference between the teen culture of today and what you wrote about 25 years ago in Reviving Ophelia?

Pipher: Early in my research for the 25th-anniversary edition, I read an eye-opening book called I Gen. Its research showed that girls in 1993, compared with girls in ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s, were at an all-time low level of psychological well-being. But after ’94, girls’ mental health started to improve, their high-risk behaviors diminished, their grades and graduation rates went up, their pregnancy rates went down, their interactions with their parents started to be more positive. On just about any index I looked at, girls were doing better.

PN: So what happened that made such a big difference?

Pipher: Part of this improvement had to do with changes in cultural education and ideas about what it meant to be a parent. The concept from psychotherapy of the “dysfunctional” family had become pervasive, but a paradigm shift happened: parents stopped asking, “What am I doing wrong?” and started asking, “How can I help my daughter deal with this culture?” Between 1994 and 2007 girls’ mental health and their behaviors became more and more positive. By 2007, measures of girls’ mental health in a variety of areas were again very positive. Then after 2007, with the introduction of smartphones, those measures fell off a cliff.

PN: In the anniversary edition of Reviving Ophelia, you write that many teens today are more attached to their cellphones than to their family. What does that mean?

Pipher: Most teenagers today have a sense of never being alone and never really being connected. They sleep with their cell phones, and the first thing they do when they wake up is grab for those phones. They get dressed while texting. They spent almost no time with other people actually talking.

The other day, I was talking with a guy who’s about to retire from teaching high school. His whole career he’d considered himself a dynamic teacher. But now, even though his students aren’t supposed to have phones in class, they’re constantly sneaking looks at them, no matter what he does to hold their attention. “It breaks my heart,” he told me. “I’ll be talking to them about truly interesting things, and I know they’re just texting away about something irrelevant.”

“In the old days, between classes,” he said, “I couldn’t hear myself think because the kids were talking so loudly. Now they’re all on phones and the halls are silent.”

These days, teenage girls’ most common activity on a Saturday night is to stay home alone watching Netflix, smartphone in hand. One of the things that’s most frightening for this age group is to be put in a situation where they have to talk to another teenager. They just don’t know how to do it. They can talk to an adult, a mother, or a father who’s asking questions, but when they have to initiate the conversation, it’s scary, because they’re used to doing everything via text.

PN: How has parenting changed over these past 25 years?

Pipher: There’s much less conflict between teenagers and their parents, because the teenagers aren’t going out. They’re home and not breaking rules. So there aren’t the traditional stresses around girls pushing boundaries to get out on their own and parents saying, “Slow down!” And, as things have gotten tougher in this culture, family is the one safe spot left. By many measures, it appears most girls don’t particularly want to become adults and leave home.

If anything, parents wish their children would go out with friends more and get a driver’s license or a job. Today’s teenagers are resisting all that. If they do go out, they often go with their parents. And if they have any kind of problem and aren’t with their parents, they text them for advice. They almost have no experience of actually being out in the world and having to solve problems on their own. So that sense of efficacy that develops from being alone and responsible for oneself, for the most part, isn’t developing. A major problem in colleges today is an epidemic of anxiety disorders among kids who have to live away from home for the first time.

PN: What other big changes have you noticed?

Pipher: A big change for teens today is that most girls in high school aren’t having sex as early as they used to. Of course, there are girls who are dating, and a minority are involved in hookup culture, where they just go find somebody to have sex with. But the vast majority of girls don’t actually date, at least not in the way my generation did. They have texting relationships, and going on a date for them means just showing up and taking pictures. Life becomes an exercise in branding instead of living. Underneath that presented self is a small, insecure self that’s not dealing well with people, with inner states, with maturational issues, with problem solving, and with emotional reactivity.

One story from my book is about a mother whose daughter was lying around all summer, complaining, watching a lot of Netflix. Finally, the mother said, “You’ve got to plan a vacation for yourself and leave home for a week. I don’t care where you go. I don’t care what you do, but you’ve got to do it yourself.” And the girl did: she got her money together and planned a trip for herself.

Another mother said to her daughter, “I’m not reminding you of any appointments or booking anything for you. You figure out what appointments you need and drive yourself to them. If you miss them, you miss them. Since you’re leaving home next year, you need to understand how to do this.” Well, it was a rocky road. The daughter made some pretty big mistakes, but she learned some really valuable skills.

PN: Your book is primarily about girls, but what about boys?

Pipher: Well, one thing to note is that pornography is everywhere, and from an early age, boys today are exposed to a brutal, objectified model of sexuality. Yet many of them may never actually touch a girl until they’re in college. This puts them in a strange learning situation. Unless the profound miseducation about the nature of physical affection and relationships gets corrected, it not only breeds misogyny, but often leads to sexual assaults. That’s not to say high school boys don’t have girlfriends or aren’t interested in having close relationships with girls, but often their primary communication with them is via text. And while some of the conversations get pretty erotic, they’re a game.

Another interesting thing is that instead of spending six, seven hours a day on social media, boys tend to be playing online video games. So they don’t seem to be as vulnerable as girls are to the whole emotional turmoil social media can create with getting likes and followers and “friends.”

PN: Given the changes you’re describing, how does the therapy of 1994 compare to the therapy of today?

Pipher: Therapists have learned that it’s hard to get girls off their phones, even during therapy. So they’ve become creative in asking girls to show them their text messages, their social media posts, so they can talk about them. When the girls are having conflicts with a friend, therapists are suggesting they bring in that friend, so the girls can learn to work out problems in person. Also, many clinicians are doing what they can to convince girls to set limits on their online behavior and to spend more time offline. The therapeutic task is to help them learn that their sense of self doesn’t have to depend on the last bleep on their cell phone.

One of the things therapists can do with girls and their parents is to figure out ways to calibrate life experiences that involve independence, problem solving, and risk taking, so that girls don’t have get overwhelmed as they learn how to navigate the real world. I think the best therapists are saying things like, “I wonder if you’d want to join any groups to help save the environment.” Or “When’s the last time you called up your grandmother?” Or “Have you taken a walk this spring in a park?”

PN: As you did research and talked to focus groups for the new book, did anything make you feel particularly out of touch?

Pipher: I didn’t realize how out of fashion dating has become. Dating was a big part of my life as a girl. I mean, I wasn’t seriously involved with anyone, but everybody went on dates. It was just part of what you did on a Saturday night. In my daughter’s generation, there was probably a little bit less dating and more traveling around in big groups of kids, but there was still a lot of direct, flirtatious interaction that might eventually lead to relationships. Today, there’s almost none of that.

PN: What do you hope readers will take away from your latest book?

Pipher: For many young people who are immersed in social media, life is not about establishing roots and making emotional connections with other people: it’s about establishing a brand. We really need to take a hard look at many of the social changes that we’ve come to take for granted and realize how our culture is creating a new kind of human being.

Rich Simon

Richard Simon, PhD, founded Psychotherapy Networker and served as the editor for more than 40 years. He received every major magazine industry honor, including the National Magazine Award. Rich passed away November 2020, and we honor his memory and contributions to the field every day.