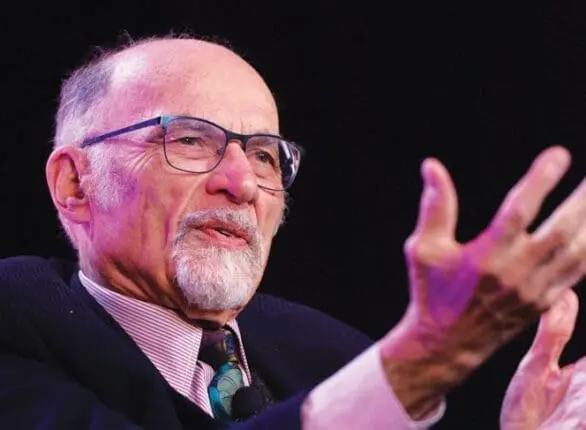

A highlight of this year’s Symposium was iconic therapist Irvin Yalom receiving the Networker Lifetime Achievement Award. In this excerpt from his recent memoir Becoming Myself, Yalom describes how, at this stage of his career, patients’ preconceptions about him can shape the therapeutic encounter.

Much as I try to deflect tokens of renown, I have no doubt they have enhanced my sense of self. I also believe that my seniority, gravitas, and reputation increase my effectiveness as a therapist. Over the past 25 years, the majority of my patients have contacted me because they have read some of my writing, and they arrive at my office with a strong belief in my therapeutic powers. Having met well-known therapists in my life, I have some sense of how such encounters can leave their mark: I can still see the crevices of Carl Rogers’s face. Fifty years ago, I requested a conversation with him and flew down to Southern California to spend an afternoon. I had sent him some of my work, and I remember him telling me that though my group therapy textbook was well-done, it was my Ginny book (Every Day Gets a Little Closer) that he regarded as very special. And the faces of Viktor Frankl and Rollo May remain so clear in my mind’s eye that if I had artistic talent (I don’t), I could render them accurately from memory.

So, because of my reputation, patients reveal secrets they have never told anyone else, even previous therapists, and if I accept them nonjudgmentally and empathically, my interventions are likely to carry more weight simply because of their preconceptions about me. Recently, during the same afternoon, I saw two new patients who were familiar with my work. The first, a retired therapist, drove to my office from her home several hours away. She was worried about her tendency to hoard (in only one room of her home) and her obsessional behavior: upon leaving home, she would drive less than a block before returning home to see whether the door was locked and the stove turned off. I told her I didn’t think these were going to be cleared up in brief therapy with me, nor were they significantly interfering with her life. I considered her a well-integrated person, someone who had an excellent marriage and was dealing with the difficult task of searching for meaning after retirement. She was pleased to hear that I thought she did not need therapy. The following day, she emailed me these words:

I just wanted to let you know how much I enjoyed and valued our consultation last Thursday, it meant a great deal to me. I felt your support and validation that I’m doing well, am happy and content with my life and really appreciate your comment I do not need any therapy. And I left your office feeling less anxious and more confident and accepting of myself. I felt that it was a true gift. That’s pretty darn good for just one session!

Later, the same afternoon, a middle-aged South American man, visiting a friend in San Francisco, came for a single consultation. He spent almost the entire hour speaking of his concerns about his sister, who has fought anorexia nearly all her life. After the death of his parents, he was so heavily burdened by the expenses of her medical and psychiatric care that he was never able to marry and have a family. I asked why he, rather than other members of his large family, had taken on the entire burden of her care. Then, with a great deal of anxiety and hesitation, he told me a story he had never before shared with anyone.

He is 13 years older than his sister, and one day, when she was two and he 15, his parents left his sister in his care for several hours while they and his older siblings attended a wedding. During their absence, he had a long erotic phone conversation with a girlfriend (whom his parents greatly disliked and had expressly forbidden him to contact). During this conversation his sister crawled out the open front door and fell down several steps, suffering very considerable bruising of her body and face. When his parents returned, he had to confess everything—the worst moment of his life—and, though his sister’s injury was slight and the bruising faded in a few days, he had harbored, all these years, a secret fear and conviction that her anorexia was caused by that fall. Moreover, in the twenty-five years since his sister’s injury, this was the first time he had ever disclosed this experience to anyone.

Using my deepest and most formal voice I told him that I had listened carefully to what he had told me about his sister and, after considering all the evidence, I now pronounced him innocent. I assured him that he had paid his dues for his episode of negligence, and reassured him there was no way in which her fall could have caused anorexia. I also suggested he explore this in therapy when he returned to his country. He wept with relief, declined my suggestion to pursue therapy, and assured me he had gotten precisely what he wanted. He left my office with a much lighter step.

These one-shot consultations, in which I recognize the patient’s efforts and strengths and offer my blessings, owe their success in large part to the power with which the patient imbues me.

Not too long ago, a woman recounted one of the saddest events of her life. In her late adolescence, just before leaving home for college, she took a long train ride with her eminent but very distant father. She had so looked forward to time alone with him, but was devastated when he opened his briefcase and spent the entire ride working, without speaking a word to her. I responded that our therapy offered an opportunity to replay that event. She and I (an older prominent man) would take a multihour therapy trip, but we would travel differently: she would have full permission, even encouragement, to ask questions, register complaints, and express feelings. And I would make sure to respond and reciprocate fully. She was moved and ultimately helped by such an approach.

And the impact of all this attention and applause upon my own sense of self? At times I feel heady and at other times disquieted, but generally I keep my balance. Every time I meet with colleagues in my support group or in my case discussion group, I am aware that they, excellent clinicians in practice for decades, are every bit as effective in their work as I am in mine. So I don’t take the adulation to heart. All I can do is take my work seriously and be the best therapist I can be. I remind myself that I am being idealized and that we humans, all of us, crave a wise, all-knowing, white-haired elder. If I’ve been chosen to fit that slot, well, I happily accept the position. Someone has to do it.

Excerpted from Becoming Myself: A Psychiatrist’s Memoir by Irvin D. Yalom. Copyright © 2017. Available from Basic Books, an imprint of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Photo by Sam Levitan

Irvin Yalom

Irvin Yalom, PhD, is an emeritus professor of psychiatry at Stanford University and the author many books, including Becoming Myself: A Psychiatrist’s Memoir.