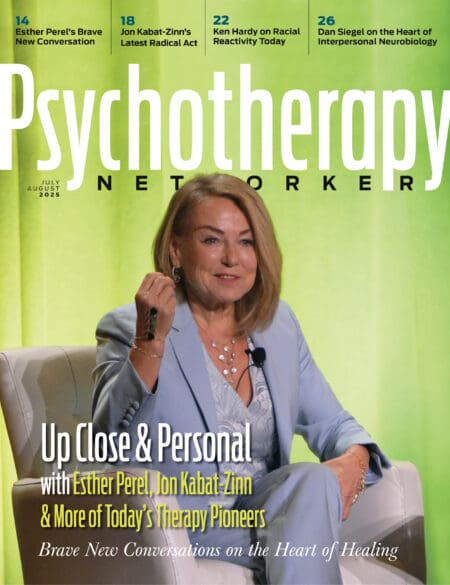

Enjoy the audio preview version of this article—perfect for listening on the go.

In 2016, the National Center for Transgender Equality released the results of a national survey showing that nearly 41 percent of the 6,450 transgender respondents reported that they’d attempted suicide at one point in their life. Other studies and surveys have reported similarly shocking numbers. I’m a trans male therapist, and through both lived and professional experience, I’ve identified several key elements that are crucial in assisting transgender individuals who are medically or socially transitioning. It’s important to keep in mind that often when we work with the transgender community, we’re saving lives.

Any therapist working with transgender individuals, including those going through gender exploration, medical transitions, and social transitions, has a duty to use correct names and pronouns, understand experiences of discrimination and harassment, and know how trans individuals can access hormones or surgery, to name a few necessities. Although I’ve connected quickly with transitioning clients in a way that isn’t always easy for cisgender therapists, this certainly isn’t to say that cisgender therapists aren’t capable of connecting with trans clients as well, but I’ve found many aren’t fully educated about the trans community.

Working with trans clients means developing therapeutic relationships with plenty of validation, normalization, and encouragement on the clinician’s behalf—and recognizing opportunities for celebration, from beginning hormone replacement therapy (HRT), to starting to grow facial hair or noticing fat redistribution, to getting top or bottom surgery. However, for some struggling clients, these events may not always feel worthy of celebration.

Discrimination and harassment force many trans clients to struggle with internalized transphobia, a both subtle and destructive process, which perpetuates depression, anxiety, substance abuse, and suicidality. In addition to establishing a strong therapeutic relationship, it’s important to recognize the thinking patterns of internalized transphobia. Such was the case in my work with one transgender client, Alex. Our therapy experience illustrates when to confront your trans clients assertively, when to be candid about the challenges and responsibilities they’re likely to face, and when to emphasize the vital importance of education.

Making a Connection

When I asked Alex, a 29-year-old Hispanic trans male, why he was coming to therapy, he mentioned depression and anxiety, but as an openly trans man myself, who specializes in working with issues around gender—as is clear on my website—I knew there were other potential reasons why Alex chose to see me.

“So what are your pronouns, Alex?” I asked.

“Whatever you’d prefer. I’m fine with anything,” he replied.

In my years working with young adults like Alex, I’ve learned that one of the biggest skills they lack is healthy boundaries and assertiveness. My intuition told me to pursue this.

“Really, which pronouns do you wish other people would use for you?” I pressed. “Or are there pronouns we could experiment with?”

Alex paused for a second. “What does it matter? They’re always going to call me ‘she’ anyway.” Alex went on to tell me he’d come out to his family as transgender a few weeks before coming to see me. It hadn’t gone well. Neither parent supported his decision to come out, especially his mother. “God doesn’t make mistakes,” she’d said, sobbing. “You’ll always be my little girl.”

Alex stared down at the floor. “They’ll never use male pronouns for me,” he said. “When I came out to them as a lesbian, they didn’t accept me then. I don’t know why I ever expected them to accept this.”

Alex had grown up in a small, conservative town in south Texas. His family and all the neighbors were Mexican-American Catholics, who, for the most part, don’t look kindly upon transgender and gender-nonconforming people. It didn’t help that he was currently living with his parents. To boot, his ex had broken up with him when he came out, telling him she “wasn’t into guys.” Alex shrugged. “I guess I should take that as a compliment,” he said.

Sensing Alex’s need for connection and recognizing our shared culture as a person of Latinx descent myself, I saw an opening and took it.

“Alex, have you heard of doing the huevo for ojo?” I asked, referring to the old Mexican belief that rubbing an egg on the body removes a curse, evil, or witchcraft placed upon it by a jealous look or evil eye—in Spanish, the mal de ojo.

Alex perked up.

“Yeah!” he chuckled. “My family always used to go to the curandero,” he said, referring to a local healer who uses folk remedies. “My mom made me do it in grade school when I started getting depressed.”

I smiled. “What was going on for you then?”

“Well, it was around the time I started feeling like something was off. I remember playing house with a few girls from school and always wanting to play the role of husband. And I always wanted to pee standing up. I was obsessed with it.”

“How about later in life?” I asked. “What was it like for you as a preteen and teenager?”

“Well, I was pretty comfortable with my body until puberty.” Alex’s eyes began to well up. “I was so depressed, and had no idea why. I was still doing all the things a girl would do: I was on the cheer squad, I wore dresses and makeup—even though I knew I wasn’t a girl. But I tried really hard to be. I just never thought I could be anything different, with my family and all.”

“I totally get that, Alex,” I said. “So, when did things change for you?”

Alex told me that he’d realized he was transgender only about a month ago, after watching a series of YouTube videos posted by young trans adults about their experience transitioning. “But I’m 29,” he said. “I’m too old to be transitioning now. Don’t most people do this when they’re, like, a teenager? I feel like an imposter, like I don’t fit in with my own community—or anyone else’s.”

Tears rolled down his cheeks. “I’m never going to look the way I see myself.”

I saw another opportunity. This time, to do a little self-disclosure.

“You know, Alex, I didn’t transition until I was almost 32. That doesn’t make my gender any less valid. I know that sometimes in the beginning of your transition you feel like there’s this burden of certainty, like you have to prove your story to others for your gender to be legitimate.” We also talked about how not everybody has the privilege or desire to start HRT or get surgery. “But this doesn’t make somebody any less trans,” I told him.

Alex nodded and wiped his eyes.

“That kind of thing can be really tough, especially if you feel like you’re not following the same path as other trans people,” I continued. “But there’s no one right way to be trans. You’re on a journey where you don’t know the end until you’ve reached the other side.”

Alex chuckled through tears. “That kinda sucks, but it’s also kind of a relief, I guess.”

“Yeah, it does,” I replied. “But we can only move forward from here, and I want to help you do that if you’d like to meet again next week.”

He gave a faint smile and nodded.

Separate Paths

Alex was 10 minutes late to our second appointment. He knocked on the door, out of breath and sweaty.

“Sorry I’m late,” he said. “I overslept. I barely got any sleep last night.”

“No problem,” I said, taking a seat. “Any reason in particular?”

“My mom and I got into it,” Alex said. “She said that this is just a phase, that I can never be a man because I can’t get a girl pregnant. I’ve been thinking about it, and now I’m wondering if she’s right.”

I took a deep breath.

“Alex, do you remember how I said last week we’re on this journey about coming into our gender? Well, parents also have a journey regarding your gender, and it’s separate from yours. Sometimes they might converge, but we need to remember that they’re two separate paths. Right now, I think your mom is grieving. Oftentimes when we’re born, our parents have an idea in their head of what they want their child’s life to look like—being successful, getting married, having children. That idea varies based on your assigned gender. So your mom is grieving the loss of her daughter. Does that make sense?”

Alex nodded.

“I feel terrible for making her feel so bad,” he said.

This is what I term trans guilt, which implies that in being transgender, we’re doing something wrong. I’d seen it often, when children came out to their parents and then blamed themselves for their parents’ distress, internalizing transphobic messages and ultimately feeling ashamed about themselves and their gender. Many parents, however, don’t realize how damaging the messages they send to their trans kids can be, often resulting in the belief that they deserve to be treated poorly, or that nobody could possibly ever accept them.

When trans clients like Alex relay these messages of internalized transphobia—this feeling of How can I be proud of myself when I’ve been taught to be ashamed? arises—it can be easy for therapists to miss an opportunity to help them dispel these beliefs.

“I just worry that I’m crazy,” Alex said. “Sometimes I doubt myself, like no matter what I do, I’ll always be a girl, even though I don’t want to be.”

“I know how difficult that is, Alex. When other people are sending doubting messages on top of the doubt you already feel, it can get overwhelming. But I want to challenge you here: would you say that about me or any other trans person?” I asked, smiling slightly.

“What?” he said, taken aback. “No, I’d never do that. I’m really sorry if I—.”

“How do you think that would make someone feel?”

“Terrible. Hopeless. Bad about themselves.”

“So why say that to yourself?” I asked.

Alex was silent for a moment. “I’ve never really thought about it that way,” he said.

“We need to maintain a balance in our thinking. One way to tell if your thinking is unbalanced is to ask yourself a question: Would I say this to a friend? If the answer is no, then you need to talk to yourself differently.”

Alex nodded, and agreed to practice this over the next week.

Even Men Have Curves

“I want to start testosterone,” Alex said as soon as he walked in the door at our next session. “How do I do that?”

It’s a question I’ve been asked before by young clients, and one I gladly assist with. I’ve got a list of HRT providers I trust, which I gave to Alex.

“Thank you,” he replied. “I realized I’m in this in-between state where I don’t feel like I’m really existing. It feels really awful, not passing as a man. At the grocery store, the cashier called me ma’am, and it really got to me. Not that he meant anything by it, I’m sure, but things like that make me avoid going out in public.” He told me he’d been wearing a binder—a device used by trans men to flatten the chest—on a daily basis, but that it got uncomfortable, especially in the Texas heat. “I don’t know why, but I always feel really anxious when I have my binder on,” he said.

“How tight is it?”

“Pretty tight.”

I’ve had both lived and professional experience with this, so decided to give my two cents. “The binder is probably making it harder for you to breathe, since it’s compressing your lungs. And since you’re taking shallower breaths, it’s probably causing your body to react anxiously.”

We discussed binding safety for a few minutes, meaning binding for no more than six hours at a time, ideally. I encouraged Alex to try a binder one size larger. He agreed to give it a shot.

“There are other things too,” he said sheepishly. “Like, I’m too short to be a man, and I have curves in my body that I hate.”

I decided to challenge him. “Alex, there are lots of short men and men who have curves,” I replied. “Next time you go out in public, try to notice the different shapes and sizes of men’s bodies. That’s what I do.”

Alex frowned.

“I get it,” I continued. “It really sucks pretransition. And I’m not going to lie to you: it’s probably going to suck for a while. If you decide to start HRT, you’ll hit some awkward stages. You’ll essentially be going through a second puberty, the right puberty.”

I gave Alex a handout that listed the masculinizing effects of testosterone, and we discussed potential risks, benefits, limitations, and alternatives. We spent the next few minutes going over it. “It’s not about passing,” I added. “It’s about unapologetically being yourself. I know gender is a social construct and our gender doesn’t even exist without others, but the most important thing is that you’re comfortable. I encourage you to explore what that might look like for you.”

Turning a Corner

“You were right,” Alex said the following week. “There are lots of guys that have a booty. I even saw a few who were shorter than me. It felt really good to see those things. I began to feel, I don’t know . . . more hopeful.”

Alex went on to tell me that he’d scheduled an appointment with an endocrinologist to start HRT in a month.

“I haven’t told my parents yet,” he said. “I want to wait until after I’ve been on testosterone for at least a few months. I don’t want them to guilt me into not doing it.”

“That’s good,” I said. “Do things as you feel ready. Remember, there’s no one right way to transition, and everybody’s journey looks different. How are you feeling about starting T?” I asked, referring to the testosterone.

“I don’t have any reservations about it anymore,” he said.

“This is an exciting time for you. Are you going to get some friends together to have a T-party? Some trans guys like to do this when they start testosterone.”

“I hadn’t thought about doing anything like that. Honestly, this doesn’t feel like something I should be celebrating when it’s causing so much heartache.”

I knew I needed to validate Alex’s pain but wanted to help him build a support system, especially since his parents probably wouldn’t be a part of it. “That makes perfect sense,” I offered. “But I really encourage you to think of this as the beginning of a new chapter in your life. A send-off party from some supportive friends could be just what you need to cheer you up.”

He gave a small smile. “Well, there are a few people I could call. I’ll think about it.”

A New Chapter Begins

A month later, Alex walked into my office with a bounce in his step. “I started T yesterday!” he exclaimed.

“Congratulations!” I replied. “What route did you decide to go?”

“I decided to do injections.”

“Did you give yourself the injection?”

“Yeah! I was really nervous, but it wasn’t so bad. Oh! And I had a party at a friend’s house. I’m really glad I did. Everyone was using the right pronouns, and I felt more like myself than ever before.”

I smiled. “That’s wonderful, Alex. Every day you’re becoming more and more yourself.”

Over the next few months, Alex’s depression lifted, and he began to feel more comfortable socially, so we switched to meeting on an as-needed basis. In our last weekly session, we talked about how he’d tell his parents that he’d started testosterone.

One day, about a year after that appointment, Alex called to schedule an appointment. When he walked into the office, I immediately noticed his new facial hair.

“It’s good to see you, Alex. How are you doing?” I asked.

“Well, I found a roommate and moved out of my parents’ house once it became apparent I was getting hormone therapy.” His voice was much deeper now.

“How’d they take it?” I asked.

“They were angry at first, but they’re starting to come around. We went out to dinner about a week ago, and the waiter kept calling me sir, but my parents kept calling me she. The waiter looked really confused. But then, this morning, my mom called me he!”

“She probably realized she can’t get away with calling you she anymore” I said.

“I think so,” he said. “She seemed pretty embarrassed at dinner.”

A smile crept over his face. “Oh, so the reason I’m here,” he continued. “I’ve got a girlfriend. We’ve been dating for the last four months. But I’m still having problems with sex, and I think I want to get top surgery. How would I do that?”

A new chapter in our therapy relationship had begun.

Case Commentary

By Margaret Nichols

Noah Garcia’s case study is notable for a number of reasons, beginning with the fact that he’s an openly transgender therapist describing gender-affirmative therapy. Up until 2013, when the DSM-5 was published, being transgender was considered a mental illness. So as recently as 10 or 15 years ago, many in his place might’ve felt uncomfortable disclosing their identity so publicly, and his client might’ve been interrogated, rather than validated, at the beginning of treatment. Today, however, gender-affirmative therapy is considered to be the standard, evidence-based approach—and Garcia has given us a beautiful example of some of this modality’s most important principles.

Garcia begins the first session by asking about his client Alex’s pronouns, thereby signaling that he’s knowledgeable about gender issues and knows that outward appearance doesn’t always reflect a person’s internal gender identity. When Alex tells him he’s transgender, Garcia doesn’t challenge or question this, even when he learns that Alex’s identification as a trans man is relatively recent. Instead, Garcia homes in on the relevant issues: Alex’s internalized doubts, guilt, and self-hatred; his fears of what the future will bring; and his family’s difficulty in accepting his identity. Garcia uses the self-disclosure that he is trans and Latinx to great advantage, but even were he neither of these things, he would’ve surely connected to Alex through his affirming stance.

Garcia’s therapeutic approach includes two things that are essential for success in working with transgender clients: validation and information. As illustrated in this case, it’s important for the therapist to validate the “rightness” and healthiness of the trans client’s identity—even when the client doesn’t feel this themself. Just as many gay people have internalized society’s condemnation of homosexuality as internalized homophobia, many transgender people have incorporated cultural disapproval as internalized transphobia. An important goal of treatment with these clients is to help them understand and eventually eradicate these self-disparaging feelings and beliefs.

It’s equally important for the clinician to know the medical interventions that may be appropriate for a transgender client, typical issues that such a client may encounter, and information about local resources. Garcia demonstrates that he’s well-informed about hormone treatment, is familiar with binders, and has a local referral list to offer his client. In addition, he frames the difficulties Alex is having with his family as “different journeys,” rather than vilifying the family. Although most parents initially have trouble accepting a transgender child, many will ultimately come to love and support them.

Garcia’s treatment approach represents a sea change from the traditional approach, widely used until the last decade or so. In the past, therapists were considered gatekeepers whose role was to restrict access to medical interventions for clients until they jumped through a number of hoops to “prove” they were transgender. Today, therapists are collaborators, coaches, and guides, as Garcia demonstrates. As someone who has practiced long enough to be familiar with both models, I can say that this one is much better for clients and more gratifying for therapists.

ILLUSTRATION BY SALLY WERN COMPORT

Noah S. Garcia

Noah S. Garcia, MA, LPC-S, NCC, is a licensed professional counselor supervisor and owner of NextQuest Counseling in Austin, TX. He’s a clinical consultant on LGBTQIA+ issues, particularly those facing the transgender community. He runs the weekly therapy podcast NextQuest Podcast. Learn more at nextquestcounseling.com.

Margaret Nichols

Margaret Nichols, PhD, CSTS, is a psychologist, sex therapist, and author of The Modern Clinician’s Guide to Working with LGBTQ+ Clients. She has more than 40 years of experience doing therapy with sex-, gender-, and relationship-diverse people, and she identifies as queer.