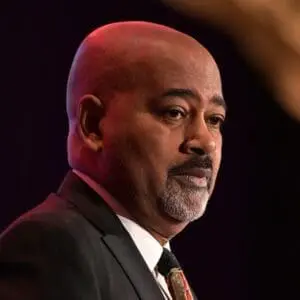

One of the hallmarks of the family therapy movement of the ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s was the exploration of the power of social issues like race, class, and ethnic background in clients’ lives. Leading figures in this movement, like Salvador Minuchin, Braulio Montalvo, Marianne Walters, and Monica McGoldrick, were outspoken about the importance of paying attention to the impact of social issues in the therapy room. But these days, we don’t hear much about the connection between psychotherapy and the larger social issues of the day. It seems that, for most therapists today, multiculturalism is a required, four-hour CE workshop, not a cause worthy of attention. One exception is Kenneth Hardy, a professor of family therapy at Drexel University in Philadelphia, who’s dedicated himself to working with troubled inner-city adolescents and keeping alive psychotherapy’s social conscience.

——

RH: You once said: “My training prepared me to be a pretty good white therapist.” Could you elaborate on that?

HARDY: I did my graduate training in the early 1980s at the Medical Research Institute in Palo Alto, and spent time at the Family Therapy Institute in Washington, D.C., with Jay Haley. I learned a great deal at both places, but there was little that spoke to me as a person of color. Whatever discussion there was about race or culture tended to pathologize people of color without seeing their inherent strengths. When I left my graduate program and got a job at a psychiatric outpatient clinic in Brooklyn working with a population that was largely people of color, I saw the first day that there was a massive disconnect between what my training had taught me and what they needed from me. While I’d been well trained, I felt like I was a white therapist in black skin.

RH: Has training changed since that time?

HARDY: Well, I think there’s been improvement. You’ll certainly find more faculty of color in training programs—not a substantial number, but one or two people. You’ll find some course content focused on themes of race, class, and ethnicity. But when I talk with students of color, the kinds of experiences they describe today are chillingly similar to the ones I experienced some 30 years ago. They still don’t feel entirely safe bringing up issues of race or ethnicity. Is it better than when I was a student? Absolutely, it’s better.

RH: You described the shift in your work with inner-city teens as moving from, “What’s wrong with you?” to “What happened to you?” Could you elaborate on this?

HARDY: Lots of the young people I see have been perpetrators and done some pretty horrific things in the world. But as a therapist, I’ve found it most useful to start by getting curious about what happened in their lives that contributed to their violent behavior or other aspects of who they are. I see them not just as perpetrators, but perpetrators who were themselves victims before they became perpetrators. So I typically ask early on, “Who were you before you became who you are today?” I want them to think about the events in their lives that reshaped them and led them to be where they are today.

The lives of these kids are filled with trauma, and trauma can reshape every aspect of our lives. As a therapist, I begin by looking at what happened along the way to clients that’s incited this shift in them. I’ve found that doing that is a much more helpful place to begin than trying to decide what’s wrong with them.

RH: What does this approach look like?

HARDY: The kids I see are coming in for things like robbery, violent crime, or chronic truancy. I’ve found again and again that trauma provides a powerful backdrop to those presenting problems. It’s really important not to start the relationship by focusing on their criminal activity. So I’m asking them to talk about their experiences of being poor, black kids in a poor neighborhood of Philadelphia, for example.

RH: You mention that a big part of your work with these young folks is affirmation. What do you mean?

HARDY: I once overheard someone talking about how a periodontist had to impact his gum and create some sort of synthetic gum. Something like that happens in psychotherapy. Often we have to build up the underdeveloped parts of people and find strengths where we can—to lay a foundation for growth. Affirmation starts to rebuild or restore what’s been destroyed, to create a foundation from which therapy can actually take place.

That’s not always so easy, especially if someone’s life narrative as a result of trauma is that “I ain’t nothing.” That can be difficult to rewrite. If I dare to see something redeemable in such people, they may think I’m trying to manipulate them. How could I honestly see something valuable in them?

RH: You like to talk about seeking out our clients’ “untapped heroism.” What does that mean?

HARDY: It comes from my deep conviction that no matter how egregious our behavior, we still have in us some redeemable qualities—something that sets off a flicker of light in the midst of everything that’s awful. So I’m always looking for that quality of what I call heroism in these young people—that part within them that’s managed to survive against tremendous odds. Heroism is this undying will to keep on keeping on, despite all kinds of adversity.

Whether you find that quality in your clients depends on what you look for. A therapist who looks for pathology sees it. A therapist who looks for strength finds it. You have to change what you look for in order to change what you see.

Ryan Howes

Ryan Howes, Ph.D., ABPP is a Pasadena, California-based psychologist, musician, and author of the “Mental Health Journal for Men.” Learn more at ryanhowes.net.

Kenneth V. Hardy

Kenneth V. Hardy, PhD, is President of the Eikenberg Academy for Social Justice and Clinical and Organizational Consultant for the Eikenberg Institute for Relationships in NYC, as well as a former Professor of Family Therapy at both Syracuse University, NY, and Drexel University, PA. He’s also the author of Racial Trauma: Clinical Strategies and Techniques for Healing Invisible Wounds, and The Enduring, Invisible, and Ubiquitous Centrality of Whiteness, and editor of On Becoming a Racially Sensitive Therapist: Race and Clinical Practice.