Ten years ago, after Jerry Dincin was diagnosed with prostate cancer, he went through a course of radiation therapy that left him cancer-free. But a few years later, he had a recurrence of prostate cancer and then, just six months ago, a routine test revealed that the disease had spread to his bones. His condition has forced him to think about death, a subject most of us try to avoid, especially while we’re still in good health.

Having received a poor prognosis and looking for support as he confronted the process of dying, Dincin, a retired psychologist, decided to join the Final Exit Network, an organization dedicated to the principle that the ultimate human right for the terminally ill is the right to choose the time and method of their death. “My relationship with the Final Exit Network is a tremendous comfort and relief to me,” explains Dincin, who’s now the president of the organization, “because I know that when my medical condition becomes too uncomfortable, I can decide that I don’t have to live with it. I’m not afraid of being dead; I’m afraid of the dying process, and the pain and suffering that goes with it.”

At a time when medical technology has become increasingly adept at keeping people alive, people like Jerry Dincin are voicing a feeling within a growing part of the population that the goal may not always be keeping a terminally ill person alive at all costs. As he puts it, “If you’re on a ventilator, you can live for a long time. But whether you want to should be put into that equation.”

Fighting for the Right to Die

Since the time of Hippocrates in the 5th and 4th centuries B.C., the principle of helping patients stay alive has been the foundation of medical practice. Generally speaking, the idea that all patients should have the right to choose death, and that any physician should be legally allowed to help them carry out their wishes, runs counter to the ethical code of the entire medical establishment. Similarly, the notion of choosing the time and method of one’s death has been rejected by most religious traditions throughout the centuries, in the belief that only a higher power should determine the time and means of death. Most faiths consider suicide a sin.

In the United States, the organized movement promoting the right to die can be traced back to the first decade of the 20th century, when a bill to legalize euthanasia was proposed—and defeated—in Ohio. About 20 years later, the Euthanasia Society of America was founded to encourage public acceptance of the concept of providing a painless death to those with incurable diseases who wished one. In 1980, Derek Humphry created the Hemlock Society to educate the public about right-to-die issues and generate support for the idea that, under certain circumstances, it might be more humane to help people at the end of life bring about their own death peacefully and quickly. The Hemlock Society drafted a model law on euthanasia and assisted suicide that’s become the basis for the legislative efforts that have followed, and the society continues to be active in promoting public support for assisted suicide today, under the name Compassion & Choices.

Beginning in the 1980s, the debate about euthanasia became increasingly public, in large part because of the activities of controversial right-to-die activist Jack Kevorkian, a physician who helped at least 130 patients die. Kevorkian, who himself just died in June, eventually went to prison for the second-degree murder of Thomas Youk, a patient with Lou Gehrig’s disease who, physically unable to carry out his own suicide, had asked that the doctor administer the lethal injection. In all his other cases, Kevorkian had merely been present when his patients had administered their own injections—which had precluded murder convictions. He was paroled after eight years on the condition that he never again provide suicide advice or assistance to anyone.

With his attraction to the limelight, outspokenness, and flare for the dramatic, Kevorkian had a mixed reputation among right-to-die activists. In a 2007 article, Derek Humphry referred to him as a “lone ranger,” who increased public polarization about right-to-die issues. “Political activists in the right-to-die movement in the 1990s dreaded the thought that Kevorkian might show up during their campaigns because he was such a negative figure,” Humphry noted. However, later in the article, he thanked Kevorkian for the “huge public interest he aroused” and his indirect role in bringing about the first legislative breakthrough for the right-to-die movement: the passage of Oregon’s 1997 Death with Dignity Act.

The Legalities Here and Abroad

The Oregon law allows terminally ill residents to end their lives through the voluntary self-administration of lethal medications prescribed by a physician. Under this law, only an adult Oregonian who’s been diagnosed with a terminal illness that will undoubtedly cause death within six months may request—in writing—a prescription for a lethal medication. Any physician, pharmacist, or healthcare provider who isn’t comfortable being part of this process may legally refuse to participate.

The Oregon law requires that the request to “hasten one’s death” (the phrasing of choice for most advocacy organizations) must be confirmed by two witnesses, at least one of whom isn’t the patient’s physician or relative. Afterward, a physician must validate the medical diagnosis and examine the patient for any possible mental health issues. If there’s any question about the patient’s mental condition, he or she must undergo a psychological exam to ensure that there’s not impairment of judgment. After the request is approved, the patient must wait at least 15 days before making a second, oral request, and the right to withdraw the request at any time is available. The entire process is set up to ensure that unwilling people aren’t being pressured to end their lives for any reason.

One of the arguments against legalizing physician-assisted suicide in America is the “slippery slope.” Many opponents fear that if hastening one’s death becomes legal in more areas and less stigmatized among the general population, people will go too far, persuading some to take the step who might not really want to, or helping others die who aren’t terminally ill. But Dincin counters the slippery-slope argument by insisting that there’s an innate drive in every human to stay alive. He agrees, however, that it’s important to be meticulous about evaluating the physical and mental health of prospective assisted-suicide patients.

Since Oregon’s law was passed, death-with-dignity legislation has been introduced regularly in other states, including Washington and Montana, which enacted such laws in 2009. Vermont may be next, as legislation is being brought up for consideration in the state House of Representatives this fall.

Internationally, similar legislation has been considered in many countries and has succeeded in such places as Switzerland, Colombia, Albania, The Netherlands, Belgium, and Luxembourg. Each nation has its own rules and procedures, but all except Switzerland forbid visiting foreigners from receiving help in hastening their deaths. The World Federation of Right to Die Societies website lists 45 members drawn from 26 countries, underscoring the broad-based support for this idea all over the world.

Only physicians are allowed to help people die in Belgium and The Netherlands. In Switzerland, which has the most liberal legislation, nonphysicians, including right-to-die societies such as EXIT, the largest such group in the country, can provide assistance. The only requirements for hastening death in Switzerland are a poor medical prognosis, unbearable pain or unsustainable impairment, and the patient’s full discretion (mental competency).

In America, the Final Exit Network—comprised of volunteers from all over the country—is one of dozens of organizations that advocate for right-to-die laws, but it’s unique because it doesn’t take on the political or legislative side of the battle. It exists simply to support people and help individuals through the process of deciding whether hastening their death is right for them. Patients seek out the Final Exit Network (the organization never seeks out patients) and explain why they’re interested in taking their own life. They’re required to send medical records that verify that they have the terminal illness they claim to have. The organization has a panel of physicians who review the records, and ultimately turn down many people. For patients to receive assistance, they must be extremely ill with an irreversible and fatal disease.

Once a patient is accepted, the organization sends a trained volunteer to the house to ensure the patient’s competency. If there’s any question at all about the patient’s mental state, the organization sends one of its affiliated psychologists for further evaluation. Once competency is proven, the volunteers discuss with the patient the specific method the organization recommends for a quick, painless, and certain end—the method they consider most dignified. The organization never directly intercedes on a patient’s behalf. “We don’t assist in ‘assisted suicide.’ We don’t even use the word. We call it ‘hastening your end,’” Dincin explains. A volunteer will be present, however, if the patient wishes that someone from the organization be there at the moment of death—a request that’s often made.

The approach in Oregon, Washington, and Montana differs by allowing assisted suicide. In these states, two doctors independently certify that a patient has an illness that’ll certainly lead to death within six months, and then provide a prescription for a lethal drug that the patient self-administers; neither doctor is present when the patient takes the drug. Dincin takes issue with the six-month requirement because there are some illnesses in which it’s impossible to determine with certainty whether the patient will die in a few months’ time; some neurological, extremely painful illnesses—ALS, Huntington’s disease, Alzheimer’s—persist over a long period.

Of course, individuals with Alzheimer’s pose a complicated problem because those in the later stages lose mental competency. Dincin believes that, in the future, people should be able to have advanced directives regarding terminal illnesses, which would indicate that if they reach a certain stage in their mental competency, and if they don’t want to live anymore, hastening their deaths would be legally undertaken. But for now, the Final Exit Network considers helping only individuals in the early stages of Alzheimer’s.

“We see hastening death as a trend that’ll gradually—very, very gradually—move through the U.S. state by state, but it’ll take decades, if ever, before it becomes the usual practice,” Dincin says. That’s why the Final Exit Network concentrates on helping terminally ill individuals, rather than working toward changing the law.

The Right-to-Die Debate

In many ways, the current debate over the right to die mirrors the dispute over abortion rights, with the two conflicting sides of the argument being labeled “pro-choice” and “pro-life.” While pro-choice organizations, like the Final Exit Network, generally believe that terminally ill individuals who are being kept alive by modern medicine should be given the means to “die with dignity” if they choose, those on the pro-life side generally believe that no one should be able to choose the timing of their own death. One of the most prominent pro-life spokespeople within the healthcare community is Ira Byock, a physician who focuses on hospice, palliative, and end-of-life care. The author of Dying Well and a frequent guest on television and radio programs, he regularly works with people who are terminally ill, many of whom seriously consider ending their lives. He believes firmly in the importance of asking people how they feel about death and listening to their perspectives on dying, but he insists that “helping a patient or client to end his or her life is never right.” According to him, doing so always results from countertransference: “It occurs when the therapist or doctor can’t imagine anything else to do for this person.”

Byock feels that for a psychotherapist to assist a client in ending his or her life is essentially to reinforce the person’s sense of helplessness and hopefulness. He adds that seriously ill people already have the means of ending their lives, so by requesting assistance, they’re really requesting affirmation. “For me to affirm this for them, I must be unable to imagine some other way to support or care for them; I must be devoid of an ability to see them as being able to be helped or having some semblance of hope,” says Byock, “and that’s not my job. My job is to always find ways to help people who are suffering, and always be able to help them perceive something tangible, valuable, to hope for in the future—even if it’s only to die gently and for their families to be supportive.”

Like Byock, Dincin thinks that healthcare professionals’ work with dying patients can be easily distorted by their own personal feelings about dying. Considering the prospect of his own death, Dincin says, “I’m married, and it’s a sad situation for us to contemplate, but there’s no question that my wife supports my attitude and whatever decisions I’d make, even if it would make her grieve.” He adds, “I have very big news for you: everybody dies. Everybody knows it at some level, but they don’t really take it in, and take it seriously. When you have to, it changes your outlook on life, and you come to look at things differently. You begin to decide what’s worthwhile and important to you.”

It would be a big step forward if psychotherapists could move away from the stance that death is always terrible, says Dincin. “I think that it shouldn’t be looked upon as a failure of the medical system if someone wants to die under such circumstances, but rather, a positive.” He isn’t advocating that anyone take his or her own life, he insists, but is promoting more openness to the option, without the stigma. “I’ve been with a number of people who’ve taken their life, and without exception, they’re overwhelmingly grateful and relieved. They’re really relieved to be out of life.”

Dincin thinks that, as a profession, psychotherapy has a responsibility to take a deeper, more thoughtful look at death, and that it’d be a great advance in healthcare if more therapists could become experts in end-of-life care. According to therapist Faye Girsh, an advocate for the right to die, such expertise begins with having more knowledge about the issues surrounding end-of-life care and terminal illnesses, and more awareness of the resources available. “It’s important for therapists to know what the organizations are, what the books are, and what kind of counseling to provide for such individuals, so that terminal patients don’t have to have the anxiety about whether their deaths will be difficult, prolonged, painful, or whether they’re going to lose control.”

***

Resources:

http://www.assistedsuicide.org/

http://www.finalexit.org/websites_and_resources.html

http://www.deathwithdignity.org/resources/

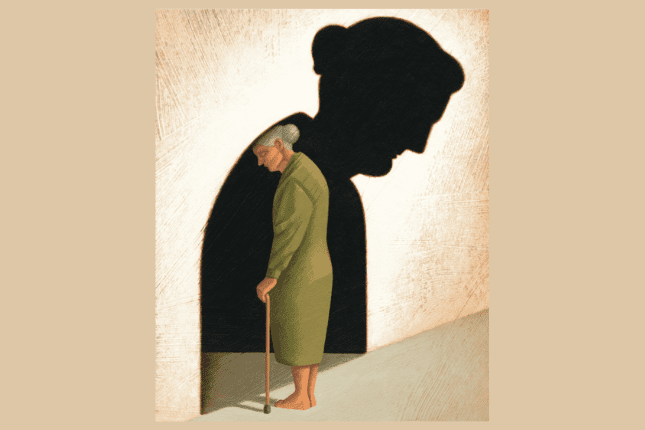

Illustration © Adam Niklewicz

Jordan Magaziner

Jordan Magaziner, a graduate of American University‘s School of Communication, is the former editorial assistant of the Psychotherapy Networker.