When I first began practicing therapy in the mid-’70s, I was already a devoted aficionado of Salvador Minuchin, even then considered by young therapists a rising hero in the relatively new (and, at the time, radical) field of family therapy. For me, and other devotees, he seemed able to cut through the knottiest family problems with his swift sword in a matter of minutes, while implicitly reducing all those old, slo-mo psychodynamic principles to mushy shibboleths of a bygone era. Indeed, I felt certain that this thrilling approach to therapy was all I’d ever need to vanquish emotional suffering with whatever clients I saw.

Well, of course, I eventually discovered just how complicated and refractory clients could be about holding on to their problems, regardless of my best efforts at wielding this wonderful, new healing tool. In fact, all good—or at least honest—therapists discover, sooner or later, that learning about therapy, even from acknowledged masters and pioneers, has little to do with actually doing therapy. No matter how much formal training therapists receive or how inspired they’ve been by this or that therapy guru, no matter how grounded their model is in up-to-the-minute scientifically validated research, or how closely they hew to the latest official guidelines for practice, they quickly run up against a few unpleasant truths. Too often, their interventions just don’t work very well, or at all. In spite of what seems to be as many different therapy methods as stars in the sky, and in spite of reams of outcome studies, no empirically studied model appears to show any real advantage over any other.

Does this mean therapy is simply useless—that we should all pack up our framed degrees, sell our therapy books, and go into real estate? Of course not. Therapy does work—often exceptionally well—but not as routinely or predictably as we’d like. Nor does it reliably work in accordance with the strict protocols of “scientific” treatment manuals. Seasoned clinicians know that practicing therapy is always more than just following the technical rules they’ve been taught. Engaging a new client is a leap into the unknown, the beginning of an exploration into uncharted human geography. Rather than strictly adhering to “the book,” so to speak, it’s often more healing to simply honor, with respect and attention and compassion, what clients bring to therapy, to follow clients into their own dark labyrinths of heart and mind, and then help them find their way out again into daylight.

Sometimes this process is predictable—just as the models describe—but sometimes it’s not. Often therapists find themselves in the dizzying role of skydivers. They’ve gotten airborne, thanks to years of reading, studying models and techniques, watching videos, listening to lectures, attending workshops. But at a certain point, the airplane door is flung open, and they must make that leap of faith, let themselves fly—arms outstretched—and hope the parachute of acquired knowledge, common sense, and pure inspiration will open in time, letting them and their clients float gently and safely to solid ground.

In this issue, we bring you several articles from very experienced therapists and researchers—all working in unique ways—who discovered at some point they had to abandon conventional wisdom and make their own leap into thin air. Their stories, I think, will prompt nods of recognition from older therapists and perhaps embolden younger ones to reexamine “official” assumptions about therapy. For these newly minted practitioners, our writers might have this advice: be careful, always, but also be brave, try a little something different, make a little magic happen.

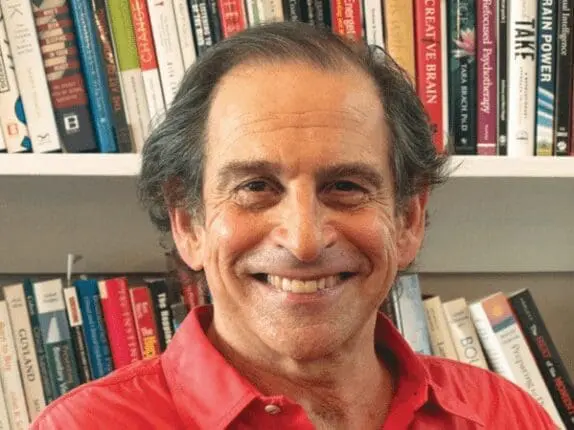

Rich Simon

Richard Simon, PhD, founded Psychotherapy Networker and served as the editor for more than 40 years. He received every major magazine industry honor, including the National Magazine Award. Rich passed away November 2020, and we honor his memory and contributions to the field every day.