Most of us are intimately familiar with the experience of growing up feeling that, at times, we didn’t measure up to whatever we thought was expected of us—we weren’t good-looking enough, athletic enough, smart enough, or just generally cool enough. Still, I remember that even when I felt most inadequate as a teen, I didn’t feel so divided within myself that I couldn’t put on a pretty good act as a “normal” kid.

But for transgender, or transitioning kids, or kids who just can’t find a comfortable home in either gender, daily life can easily become a battlefield, on which the most ordinary, taken-for-granted activities are sources of relentless conflict and struggle, both inside themselves and with others. What bathroom should they use? Where should they go when told to line up with the other boys or other girls? What name should they be known as? What pronoun best suits them? What clothes should they wear or not wear? And these question don’t even take into account the continual feeling of living in the “wrong” body.

There’s no comfort in faking it, because something as pervasive as gender really can’t be faked. And there’s no escape—except a doomed attempt to constantly and unrelentingly hide the truth and pretend to be what one isn’t. But people can’t forever fake being something or someone they’re not, and the costs for kids who are forbidden to be genuinely themselves, who are often expelled from their own homes, are almost unimaginable loneliness and pain. There’s a reason for the shocking suicide attempt rate among gender-nonconforming people.

I found talking to the transgender kids and their parents that I interviewed for this issue not only enlightening and educational, which I expected, but also viscerally moving. I was bowled over by the stubborn integrity of young kids who would insist upon being who they feel themselves to be, regardless of what anybody thought. Where, I wondered, did they find that spirit, that audacity, that sheer heroism, and at that age? But, then, talking to the parents of these kids, I began to understand a bit better. Here were almost always loving, devoted parents who wanted to protect their kids and stand up for them, no matter what. Even more importantly, here were parents whose clear-eyed selflessness allowed them to realize, in a way that perhaps most parents don’t, that their children were not put on this earth simply to fulfill parental expectations and become chips off the old block. These parents were fundamentally willing to put aside their own ideas and dreams of what their children should be to give them the space and the time and the freedom to be their own selves, regardless of how emotionally wrenching it was for them as parents.

This issue’s exploration of the experience of being transgender may seem quite radical to many readers—after all, even the term transgender was unknown to most people until a scant decade or so ago. And yet, talking to the parents and children in the families who agreed to share their stories with us, it began to dawn on me that maybe all this transgender stuff isn’t so foreign after all. In fact, human nature—whatever that is—is far more varied and complex than the age-old, rigid, binary division that HE/SHE would suggest. Indeed, maybe our ideas of what’s “natural” don’t need to be completely junked—they’re just due for a tune-up.

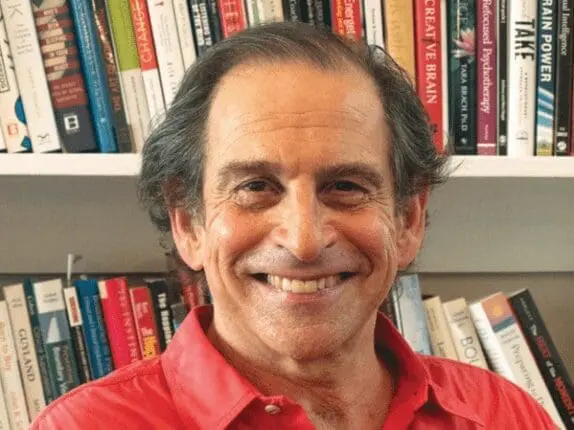

Richard Simon

EDITOR

Rich Simon

Richard Simon, PhD, founded Psychotherapy Networker and served as the editor for more than 40 years. He received every major magazine industry honor, including the National Magazine Award. Rich passed away November 2020, and we honor his memory and contributions to the field every day.