While wrapping up this issue about our total submersion in (or capitulation to) the digital culture, I remembered a movie I saw more than 50 years ago, long before the smartphone was even a tech nerd’s fever dream. Called The Servant, this movie—not a sci-fi flick, nor remotely about computers—now seems an odd premonition of our current fraught relationship with the internet. A quietly foreboding drama set in mid-’60s London, the film is about a manservant, played with unctuous menace by Dirk Bogarde, who gradually insinuates himself into the house, the life, and finally the mind of his master—a puerile, clueless, upper-class gent who doesn’t realize until too late that he’s no longer in charge. By the end, the servant—so obliging, so efficient, so helpful, so softly ingratiating—has become the master, calling the shots, while the putative “master” has been reduced (semi-willingly) to submissive dependency.

This kind of comparison can sound a bit overwrought. Even if the diagnosis of “internet addiction” is legitimate (and many experts think it isn’t), surely it can’t apply to the billions of people on the planet whose gizmos seem permanently grafted onto their persons. Anyway, we are still more or less in control of these wonderful tools and toys, aren’t we?

I’m not sure, nor, I suspect, is anybody else. Over the last two or three decades, we’ve called forth electronic spirits (or, for all I know, tiny elves inside our devices) that have acquired such a prominent place in our lives that it’s hard now to remember life without them. How did we while away the hours back when we weren’t continually tapping at a screen? And why would we want to return to those dull, leaden days BI (before internet), anyway, when we now have these wonderfully adaptive, helpful, entertaining, even magical “servants” we summon, which amplify our lives, our personalities, our ability to do things that were impossible in the old, predigital world. With these handy-dandy little wizards in our hands, we can become smarter, more knowledgeable, better informed, more socially connected, certainly more entertained. Suddenly, our small, isolated, inadequate selves become so much more richly endowed. It’s all great, right?

Well, certainly in some ways, but not entirely, and often not at all. The internet is a powerful presence in our lives—arguably as dynamic and compelling in its influence as any human relationship we have. The screen is a (virtually) living presence in our consciousness, a strangely animated being in its own right: the ghostly mimic of a best friend, always there for us, always ready, and always inclined to hog more of our attention than any of our more traditional connections.

As therapists, what, if anything, can we—should we—do about this? How are we even to think about it? It’s not reassuring to know that, as we read in this issue, some of the planet’s most brilliant behavioral psychologists are beavering away at tech companies to develop oh-so-user-friendly digital systems that employ sophisticated forms of operant conditioning to bend us to their will. The internet has moved into all of our homes, wedged itself into the crevices and crannies of all of our lives. The rabbit won’t go back into the hat, the genie into the lamp—they remain out there, alive, rambunctious, and greedy for constant attention. As the technology and its ubiquity increase, more and more the question becomes, between ourselves and our devices, how do we make sure who’s the boss?

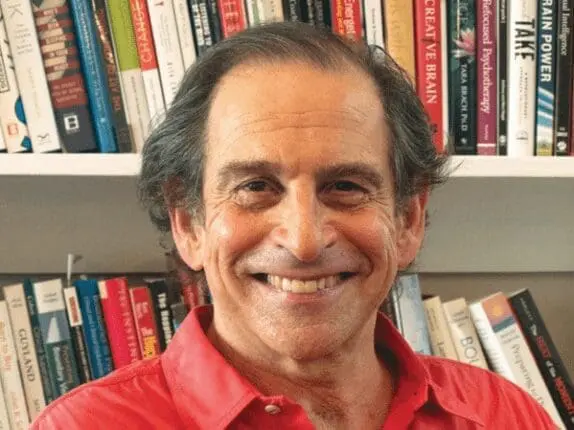

Richard Simon

EDITOR

Rich Simon

Richard Simon, PhD, founded Psychotherapy Networker and served as the editor for more than 40 years. He received every major magazine industry honor, including the National Magazine Award. Rich passed away November 2020, and we honor his memory and contributions to the field every day.