For generations, the divide between the hard sciences and psychotherapy seemed impassable. Science was the systematic, methodical search for predictable rules defining the properties and behavior of objective, measurable phenomena in the real world. Psychotherapy was the intuitive, touchy-feely pursuit of subjective well-being by one person (“client” or “patient”) with the help of another person (“therapist” or “counselor”). While real science took place in high-tech laboratories with specialized equipment, therapy required nothing more than a quiet room and a couple of comfy chairs. Sure, for decades there’s been an empirically based “science of psychotherapy”—complete with manualized protocols of prescriptive treatment rules. But nobody seriously put this science into the same category as that science, which only makes therapists’ current infatuation with brain science all the more unexpected.

Like a kind of brain fever, the fascination with neuroscience and the dogged attempts to drag insights from it into the practice of psychotherapy have infected vast swaths of the field. At therapy conferences these days, the polysyllabic terminology of neurobiology seems to pop up everywhere. But like every passionate love affair, this one was probably too hot not to cool down. More and more therapists have begun wondering how far all our impressive-sounding talk about the brain has gone in improving therapy’s effectiveness. After all, dropping stray neuroscience factoids into therapy sessions doesn’t equal “brain-based” therapy.

So we’ve decided to ask some challenging questions about our profession’s infatuation with the brain: when all is said and done, has brain science actually lived up to its promise for psychotherapy? What specific clinical advances, if any, have been guided or encouraged by knowing more about neuroscience?

With all our glib oversimplifications of the complex workings of the brain, have we just fallen for a 21st-century version of phrenology—the old pseudoscience that identified every mental function with its own distinct localized brain module?

A look at the articles in this issue will reveal answers to these questions that are both unexpected and paradoxical. As you’ll see, what might be called “big brain knowledge” (as opposed to “little brain science nuggets”) opens the way for some genuinely new and potentially far more effective treatment strategies than we’ve had before. But first we need to embrace the fundamental lesson of how to best change the brain. To get at the unconscious processes and built-in negativities that normally lie beneath awareness—that is, to change the brain—the therapist must still help the client do the old-fashioned, 19th-century work of training the mind. In other words, the therapist must get the client to take the time and expend the effort to actively learn a new way of thinking and feeling—not sit passively and wait for some new knowledge about the brain or neurotechnology to bring about a magical transformation.

And, in perhaps the most paradoxical finding of all, this kind of change is best accomplished in the context of a warm, emotionally resonant relationship between therapist and client. In a culture filled with skeptics about the touchy-feely world of psychotherapy, “hard” brain science has affirmed the crucial necessity of the traditional “soft” skills of therapeutic connection.

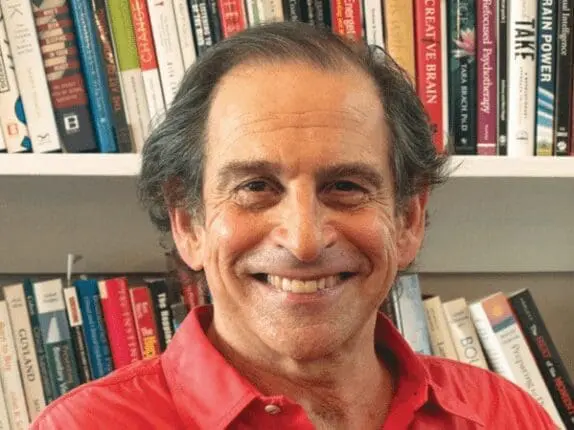

Richard Simon

EDITOR

rsimon@psychnetworker.org

Rich Simon

Richard Simon, PhD, founded Psychotherapy Networker and served as the editor for more than 40 years. He received every major magazine industry honor, including the National Magazine Award. Rich passed away November 2020, and we honor his memory and contributions to the field every day.