To our ancestors, death was no secret. They knew how to sit at a deathbed. They had customs and books to guide them—and plenty of practice. Take, for instance, death’s presence in the lives of my great-great-great-grandparents, Philippa Norman, a household servant, and John Butler, a brush-and-bellows maker. Poor Quakers, they married in Bristol, England, in 1820 and soon had four children, two of whom died before their second birthdays.

In hopes of a new life, John sailed to New York on the ship Cosmo; Philippa and their surviving son and daughter followed the next year. There Philippa gave birth to a stillborn son and later sat at John’s bedside as he died of tuberculosis, now preventable with vaccines and treatable with antibiotics.

Widowed at 36, Philippa returned to Bristol, where her daughter Harriet died of tuberculosis at 22. Her only surviving child married and had seven children—one of whom died at 13 of typhoid fever at a Quaker boarding school.

In your own family tree, you’ll probably discover similar stories.

We who live in developed countries now inhabit a changed world. Thanks to clean water, vaccines, antibiotics, and advanced medical technologies, many of us know little of death before we ourselves, or our parents or closest friends, get vulnerable or old. Then death awaits us, often in shapes our ancestors would not recognize. To postpone it so long often means we meet it unprepared.

Consider my apparently vigorous father. At the age of 79, he put on the kettle for tea and had a devastating stroke. In an instant, he entered a prolonged “gray zone” between active living and active dying. Nobody in our family had a map of this unfamiliar landscape, or a guide to another unknown country: the bewildering subculture of advanced medicine. We knew little of the peculiar problems of modern death, especially the harm medicine can do when it approaches aging bodies as it would those of the young.

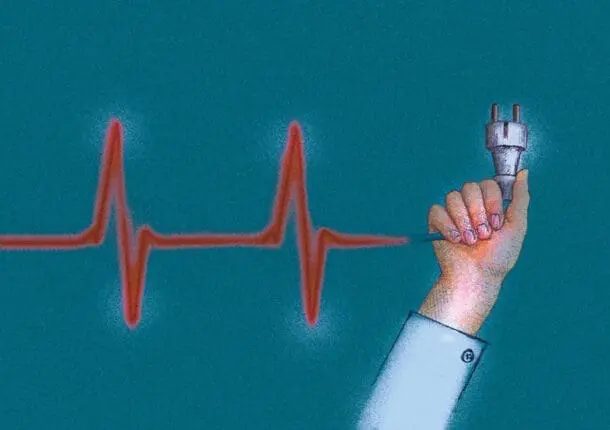

Two years later, after a hasty decision that everyone in our family came to regret, my father was given a pacemaker to correct his slow heartbeat—a device that, in his words, made him “live too long.” He spent his last six and a half years dependent on my exhausted mother, descending into deafness, near-blindness, dementia, and misery. Five months before he died, my mother and I asked to have his pacemaker deactivated. His doctors refused.

He finally died on an inpatient hospice unit after my mother and I quietly decided not to allow his pneumonia—once called “the old man’s friend”—to be treated with antibiotics. We sat by his side in a clean simple room, reassured by hospice nurses, and holding his hand. I was 59 then, and had never before sat at a deathbed.

Perhaps it was my great good luck to have been shielded for so long. It was also my burden. I had little knowledge of the “habits of the heart,” long practiced by our ancestors, that can make dying a sacred rite of passage.

In my ancestor Philippa’s day, dying took place at home. But by the 21st century, my family, like most, had delegated the management of dying to medicine. In the span of a couple of centuries, the shape of dying itself had been transformed—from a single brief crisis to a slow and attenuated process that can last years. Neither our family, our culture, our language, our expectations, our medical systems, nor our government services have yet caught up with this change in the shape of death. And it’s slowly dawned on me that medicine, to which our family had unthinkingly delegated so much power, had warded off my father’s death far more successfully than it had prepared us for a peaceful one.

As a culture, we feel this loss. We hunger to restore dignity, community, and honesty to our final passage. We want to die as full human beings, not as bundles of diagnoses. We sense that something has been forgotten. We want more than pain control and a clean bed. We want to die well.

Dying as a Rite of Passage

In the mid-1400s, an Italian Catholic monk wrote a self-help book called Ars Moriendi, or The Art of Dying. Illustrated with woodcuts for the illiterate, it taught laypeople how to navigate the physical and spiritual trials of the deathbed. A bestseller, it was translated into most major languages of Europe and went through 65 editions before 1500.

In its woodcuts, a gravely ill man or woman lies in bed, attended by friends, spouses, angels, and sometimes a favorite hound. Beneath the bed are demons, urging the dying person to give in to one of five “temptations to sin” that block the way to dying in peace: lack of faith, despair, impatience, spiritual pride, and what the monk called avarice—or not wanting to say goodbye to the cherished things and people of the world. Such emotions—fear of the afterlife, remorse, wanting to die quickly, and not wanting to die at all—are familiar to most who have sat at a deathbed.

The antidote, counseled the Ars Moriendi, was not to fight bodily death by medical means, but to care for the soul. The dying were to “commend their souls” into the hands of God and, ideally, relax into a state of grace. The soul, pictured as a tiny human being, would leave the body and fly to heaven in the company of angels.

To the medieval mind, the dying were not passive patients, but the lead actors in their lives’ final drama. Even on the deathbed, people had choices and moral agency. For the next several centuries, dying would be viewed as a spiritual ordeal and a domestic ritual, as significant and as ordinary as a baptism or a wedding.

Children, dogs, and even neighbors would gather at the bedside. Prayers would be spoken. A priest or rabbi might visit. Candles would be lit. After the final breath, relatives or religious volunteers would wash and dress the body—a practice echoed for millennia in every major world religion.

In America today, church bells no longer toll when someone dies. In hospitals and nursing homes, the dead are zipped into body bags and gurneyed out back elevators, as if death itself was a shameful and frightening failure.

There’s a gap nowadays between how we hope to die, and how we really do. More than three-quarters of Americans hope to die at home like their ancestors, but more than two-thirds die in hospitals, nursing homes, and other institutions. Nobody I know wants to die “plugged into machines,” but nearly a third of Americans stay in an intensive care unit (ICU) in their final month; 17 percent die there.

In antiseptic rooms where pets, flowers, candles, children, and unmarried partners are frequently forbidden, hospital protocols replace ancient rites. The dying often can’t say their last words, because they’re sunk in chemical twilights, or have tubes in their throats. Relatives pace the halls, drinking bad coffee from vending machines, shocked to hear—often in a drab conference room—that someone they love is about to die. ICU nurses and doctors sometimes use the word torture to describe what happens when a doctor, or a family member, refuses to accept the inevitable. Treatment often doesn’t stop until someone gathers the courage to say no.

It doesn’t have to be this way. There’s a pathway to a peaceful, empowered death, even in an era of high-technology medicine. It begins long before the final panicked trip to the emergency room. It usually requires not a single dramatic letting go, but many microdecisions, made along a series of forking paths. It requires navigating a medical system poorly structured to meet the needs of anyone facing an incurable illness.

Our current system pours its money, energy, and time into saving lives, curing the curable and fixing the fixable. In its division of labor, it looks like an assembly line. Each specialist works on a single organ and puts the body back on the conveyor belt. Every year, this “fast medicine” track saves countless victims of violence, car accidents, and heart attacks. In a crisis, it works very well.

But when people confront multiple health conditions that can be managed but not fixed, the conveyor belt poses great risks. In time, every body becomes globally fragile. Now, fixing things organ-by-organ, and assuming that living as long as possible is every person’s paramount goal, can create obstacles to living well and dying in peace. Elderly people and the terminally ill find themselves shuttled from specialist to specialist, from test to test. Nobody speaks about where things are heading. And so people often ride the conveyor belt to its ultimate destination, a high-tech hospital room. And there, in a place where success is defined as not dying, they die.

In the years I’ve spent listening to people’s stories of good and difficult deaths, I’ve learned one thing—people who are willing to explore the sometimes painful terrain of their own aging, vulnerability, and mortality often live better lives, and experience better deaths, than those who don’t.

They keep shaping lives of comfort, joy, and meaning, even as their bodies decline. They articulate what makes their lives worth living and stop chasing cures when those conditions can’t be met. They get clear-eyed about the future, so they can plan. They regard doctors as consultants, not bosses. They find medical allies to help them live as well as possible for as long as possible, and to support them in good deaths. They enroll in hospice earlier, and often feel and function better—and sometimes even live longer—than those who pursue maximum treatment. They make peace with the coming of death and seize the time to forgive, to apologize, and to thank those they love. And they often die with less physical suffering, and just as much attention to the sacred, as our ancestors did.

Everything Broke Her Way

In my research, I found that people who died well were not necessarily the mentally sharpest and healthiest, or those with the most seeming advantages or the deepest spiritual life. Because dying well is relational and requires the help of others, a good one often hinged on small and big systems, such as a loving family and a decently coordinated health care system.

Louise Manfreddi, for instance, was the daughter of poor Methodist ministers. Her husband, Gene, was a house painter. They lived in Syracuse, where she worked as a school aide, raised two daughters, gardened, read voraciously, and started a feminist consciousness-raising group. When she was in her mid-50s, she suffered a crippling brain bleed and could never again manage daily life on her own. In an instant, she was catapulted into a degree of dependency that many people avoid until at least their mid-80s.

In time, she learned to walk and talk again, partly by watching Sesame Street. She could read an article, but not a book, could microwave a cup of coffee, but not make it from scratch. Eventually, she and her family adapted to the realities of her new life. It wasn’t easy. She had to stop gardening and driving, but she returned to keeping up with politics and seeing family friends. She volunteered as a greeter at her church, often sitting in a pew with people who’d come alone.

On the face of it, this doesn’t sound like the groundwork of a promising death. Louise suffered a longer period of disability than most older Americans, even in an era when long declines are the norm. But she died a better death than many people I know with more money and education, and Rolodexes full of influential names.

One octogenarian I know—a retired IBM executive, who suffered from Parkinson’s and dementia—had a dedicated, informed daughter, a signed advance directive, and plenty of money. Yet he was shuttled from assisted living to hospital to nursing home and back again nine times in his final year. Louise, by contrast, had the extraordinary luck to be diverted from the disjointed medical care experienced by most American elders and into an integrated program that supported her from first contact to final breath.

Louise’s pathway to a good death started, oddly enough, with a botched colonoscopy when she was 76. She was taken to a local hospital for surgery, where a perceptive social worker saw that Gene was spent. In a tearful family meeting at the hospital, the social worker persuaded Louise to enter the dementia unit of a local nursing home. The stay gave Gene a much-needed break, but Louise, far more mobile and alert than her fellow residents, soon wanted to go home. Although Gene couldn’t manage alone any more, he balked at selling the house and moving with her into assisted living.

It was then that Louise’s oldest daughter, Sylvia, found the Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE). Federally funded with Medicare and Medicaid dollars, its mission is to keep fragile people at home by providing extensive support to their caregivers. A program was just starting up in Syracuse, modeled on a pioneering effort called On Lok, begun in 1971 in San Francisco’s Chinatown. Started by a social worker and a dentist, On Lok was never intended to be a pathway to a good death. But it turns out that supporting a good life does that job quite well.

As soon as Louise entered the program, her family’s life changed. An occupational therapist assessed the house, and a PACE handyman made it safe by adding grab bars and railings. A PACE social worker helped the couple fill out the daunting paperwork required to qualify for Louise for Medicaid (which, along with Medicare, paid for PACE) and got them to prepay for their funerals.

Making burial plans flowed naturally into talking about the end of life. The social worker arranged for a Medical Order for Life Sustaining Treatment (MOLST), a detailed advance directive, signed by a PACE doctor. In it, Louise chose Gene and Sylvia to make her decisions when she could no longer make her own.

Most practical and medical care of the elderly is provided in disconnected medical silos, and the vulnerable and their burdened caregivers are expected to hop from one to the other. But PACE made no distinction between curative medicine, rehabilitation, social work, having fun, and practical support. It provided them all, including a van to a daycare program where Louise could get her hair done for $10, take trips to view fall colors and Christmas lights, enjoy visiting musicians, and see a podiatrist and a physical therapist too—all at no charge to the family.

Most Americans covered by Medicare can’t get medical care at home unless they’ve been diagnosed with a terminal illness and go on hospice. They must admit they’re dying and forswear all medical treatment focused on cure. But PACE paid for cataract surgery and expensive injections to slow the progress of Louise’s macular degeneration. It paid for eyeglasses, dentures, and hearing aids (unlike Medicare) because hearing well keeps people social, and happily social people are less likely to have their dementia worsen.

A PACE attendant came to the house to help her bathe, and when Louise got sick, a nurse came. PACE sent home plastic-wrapped packets of her medications, so that all her husband had to do was give them to her at the right times. When she became incontinent, it delivered the right-size diapers. “That meant that my mother could live with my dad, who had no special training,” said Sylvia. “He could concentrate on being her husband and keeping the house together.”

The Harbinger of Final Decline

In her last year of life, Louise stopped being a greeter at her church, went to the daycare center less, and grew weak and quiet. She lost 10 pounds. It was evident that she was in steep decline. She grew gently delusional, congratulating one daughter for a nonexistent work promotion, and consoling the other about an imaginary financial crisis. She lost the ability to swallow vigorously enough to prevent food from entering her lungs and endured a bout of pneumonia, treated with antibiotics at home.

At this point in the life cycle, especially when people are in nursing homes, medical staff sometimes suggests a feeding tube to reduce the risk of pneumonia. But Louise didn’t want one. Instead, PACE attendants came to the house to puree her food, and everyone turned a blind eye to the fact that Gene also fed her ice cream. It was a tacit tradeoff: to allow her simple pleasures rather than turning what remained of her life into a grim death-postponing project. Without anyone saying so aloud, the focus of her medical care was shifting toward what medical professionals call “comfort care.”

Shortly before Thanksgiving in 2015, Gene woke up in terror in the middle of the night. Louise was struggling to breathe, making horrible, rattling sounds. Louise again had pneumonia. When the ambulance arrived at the hospital, Gene wasn’t sure his wife would survive the next 10 minutes. Nurses set up a thin nasal tube to deliver high-flow oxygen and inserted intravenous lines for antibiotics. Louise rallied at first, but she didn’t get better. Each day she got worse.

After a week, doctors asked her and her family to consider a thoracentisis. A long needle would be inserted between her ribs to draw out the fluid that was building up in the space between her lungs and the chest wall. It would help her breathe better temporarily, the doctors said, but it would be painful, not cure the problem, and carry its own risks. As Sylvia remembers it, “My sister Anne asked the doctors, ‘If it was your mom or your sister, would you do it?’ They danced around it with their words, but with their eyes and their faces, they said no.”

Louise had insisted that the fluid wasn’t bothering her, so Sylvia said, “Let’s not do it.” She and her sister were guided in part by conversations the family had had around the kitchen table years earlier, lamenting a beloved relative who’d spent years curled up on a feeding tube in a nursing home. They were helped by the fact that Louise had expressed her medical preferences when she entered PACE. “When it became apparent that this was not going anywhere good,” Sylvia remembers, “the MOLST gave us exactly the guidance we would’ve wanted.”

At this point, a medical team with a different philosophy, in a less well-coordinated medical system, might’ve gently persuaded Louise and the family to submit to the procedure. Doctors could’ve tried ever more powerful and exotic antibiotics. If she’d been a nursing home resident without close family to protect her, she might well have ended up in intensive care, and died there.

This didn’t happen.

Ten days after entering the hospital, Louise stopped eating and drinking. A social worker from PACE convened a family meeting. Gene sat at the foot of his wife’s bed with his head in his hands, while his two daughters took seats at either side. Standing near the head of the bed were a young doctor-in-training, a supervising palliative care physician, two social workers, and a nurse. They were all there to discuss what doctors call “goals of care.”

Sylvia doesn’t remember the words the young doctor used in his first fumbling attempt, nor what the supervising doctor said when he stepped in and gave it a second try. “They were talking medical,” she remembers. “They just danced around it. Finally, I got exasperated. I grabbed Dad’s hands and said, ‘Let me see if I can summarize. What these nice people are too kind to say out loud is that we’re discussing what kind of death we’re going to give Mom.’”

Everyone exhaled. “The elephant in the room was acknowledged,” Sylvia said, “and everyone was free to be more specific.” The doctors asked whether the family would agree to take Louise off antibiotics and stop the intravenous saline drip keeping her hydrated. It would make her more comfortable not to be tethered, they said, and might allow her to die a little easier. Perhaps the family would like to think about it overnight.

The family didn’t feel pressured or even nudged. “If we’d said we wanted maximum treatment, they would’ve done it,” Sylvia said. “We were given the time to make our own decisions.” With tears running down his face, Gene looked up. “What’s the point?” he sighed. Louise had often joked that if he dared to die first, she’d kill him. “She wanted to go first. Let’s give her that.”

But if Louise left the hospital, where would she go? Her daughters weren’t keen on having her die at home under hospice care. “We wanted to be present with her as family and not be her care staff,” Sylvia remembers. “And we couldn’t imagine that our father would ever want to sleep in that bed again.”

The PACE social worker then suggested The Cunningham, a high-rise nursing home. Thanks to a federal grant, the top floor had been turned into a beautiful palliative care and hospice unit. Louise went there by medical transport van.

A good death is judged not only by the peace and comfort of the dying person, but its emotional legacy: the memories that inhabit, or haunt, those who survive it. Sylvia vividly remembers the Cunningham’s oak paneling and expansive views of the valley. The families of the dying weren’t huddled around a vending machine drinking bad coffee. Instead, they gathered around a fireplace in the living room, prepared meals in a kitchen, and ate together around an oak refectory table.

The attendants (known as anam cara, or “soul friend” in Gaelic) were encouraged to nurture relationships with residents, not punch out tasks. The oak-paneled walls, the furniture, the kitchen, everything said: You are not a patient; your dying is a human, not a medical, event. You and those you love will be cared for, and you will die in beauty.

Medicine was fulfilling its last, often forgotten duty: to attend the dying. Louise’s room was spacious enough for two cots, and there the two sisters slept for the four days it took their mother to die. In the daytime, they’d wheel her bed over to the window, hold her hands, and look out over the hills, lakes, valleys, and clouds. They heard not the beeping of cardiac monitors, but music Louise loved—recordings of strings, flutes, and Christmas music that Anne played on a boom box borrowed from staff members.

Each day, Cunningham staff brought the sisters food, so they only left their mother’s side when they wanted fresh air. Every two hours, the anam caras gently washed and turned Louise to keep her clean and comfortable, so her skin didn’t break down.

Dying can be ugly, and families and friends thirst for beauty. Louise didn’t look beautiful. Her skull showed through her skin. Her body was skeletal. Strands of her thin grey hair were plastered to her head. A plastic oxygen tube trailed from her nostrils. She was incontinent. But there was a pink quilt on the bed, and her hand was curled around a pillow embroidered with a heart and brought in by Anne. The emotional and spiritual needs of the family remained at the center of things, and frantic medical attempts to ignore or forestall death had no place.

Louise had always believed in a loving God, but she’d never placed much stock in the notion of hell. “Do you think there’s a heaven?” she’d sometimes asked Sylvia. “I don’t think there are fluffy clouds,” Sylvia had said. “But the energy is never lost.” When Louise was near death, Sylvia asked her mother if she was afraid of dying. “You could see her gathering all her resources and pulling herself up to consciousness. She said, ‘No.’”

On the morning of the fourth day, Louise’s hands and feet turned a dusky blue. Her breathing grew slow and ragged. After washing her and cleaning her bed, an attendant named Cesar, originally from Puerto Rico, asked, “Is it okay if I pray for your mom?” The sisters stepped aside, and Cesar anointed Louise’s head and body with fragrant oils and conducted a small service, reading to her softly from his Spanish Bible.

A few hours later, Sylvia saw that her mother’s breaths were coming farther and farther apart. She took her hand and told her that she’d been a good mom and it was okay to go. She held a phone up to Louise’s ear, and Gene, who’d found it too painful to be at his wife’s side much, told her how much he loved her. Hearing Gene’s voice, Louise took her final breath. She was 84.

Outside the window, a hole in the clouds broke open and the sun came streaming through. Then the opening slowly filled with clouds again. This came, for the Manfreddi sisters, at exactly the right time. “We felt that was how and when our mother finally left her body,” Sylvia said. “That was when heaven, the universal consciousness, or whatever you believe comes next, opened to embrace her.”

Fifteen minutes later, a nurse came into the room, listened for a heartbeat, and accepted the sisters’ report of the time of death. “It was empowering because our word wasn’t challenged, and we weren’t berated for not calling in an ‘authority,’” Sylvia remembers. “It made her death and our vigil feel like a personal and familial rite of passage, not a legal event.” The sisters kissed their mother’s body goodbye, tucked the covers under her chin, and left to be with their father.

Louise’s family was neither exhausted nor broke. From the day she entered the PACE program until she took her last breath, the care she got—far broader than what we usually think of as “medicine”—had been attuned to her needs and what she and her family valued.

The aftertaste of her death was not bitterness or bewilderment, but gratitude. “It brings tears to my eyes to think about her passing, but they are tears of feeling the loss, not about how or why she died or anything we did or didn’t do,” said Sylvia. “She didn’t have to suffer through a long nursing home residence or hospital stay. I am comforted that our family and community could give her a good death, without pain, and almost in her own bed. We have no regrets and only hope we are privileged to make our own departures with as much grace. It was a perfect storm. Everything broke her way.”

The Rest of Us

This death is a model for the nation. Everyone facing steep decline—not only those who qualify for hospice—should have access to this level of coordinated medical and practical, even spiritual, care. It’s a travesty that our society spends so much money on last-ditch, Hail Mary medical treatments while depriving so many of the simple supports they need to die peacefully.

I wish I could promise that you, and those you love, will pass through the difficult passages of later life as well as Louise did. But I can’t. She had the good luck to live in a place blessed by an excellent integrated health system, started and run by altruistic people with something other than profit in mind. She had an assertive, diplomatic daughter with a backbone to act as her medical advocate. And finally, she had the PACE program, which places its clients, not institutional convenience, at the heart of its mission.

For many of the rest of us, our final years will probably be, at times, chaotic. It’s widely acknowledged that the conventional medical system—at least in its approach to the aging, incurably ill, and dying—is broken. You and those who love you are walking a labyrinth full of blind alleys, cracks, and broken steps. You’ll have to navigate what the 2014 Institute of Medicine’s report on Dying in America called “a fragmented care delivery system, spurred by perverse financial incentives” and a tragic “mismatch between the services patients and families need and the services they can obtain.” In such an environment, even a good-enough decline, and a good-enough death, are a triumph.

Of course, there are people who are improvising ways to make our last months, and theirs, more humane. They include a quiet army of medical people, the many informal circles that organize the care of a dying friend, and the millions of paid caregivers who regard their poorly compensated work as a calling.

The challenge for our society is to take what are now scattered experiments, fueled mainly by philanthropies, Medicare pilot programs, and the altruism of individuals, and make them the standard of care for everyone undergoing the expected transitions of the last quarter of life. This will require a revolt from the bottom up. We deserve more, we should expect more, and the healthcare dollars to pay for it are already being spent, but mainly on expensive, harrowing technologies that do little lasting good.

Some version of the PACE pathway, tailored to fit individual needs, should be available to every declining, incurably ill, and dying person in America. All fragile individuals should get physician house calls. Anybody who needs medical care at home should get hospice care—not only those whose diseases march fast enough to predict death within six months.

To do so will require a change in the reimbursement system.

Today, the most poorly paid people in medicine are those who meet the needs of incurably ill people, and are honest about the reality of death. An oncologist who tries to understand what matters to his patients, and encourages them to explore hospice, will get poorer reviews, and make less money, than the one who never tells the truth and administers futile and grueling, but well-reimbursed, chemotherapies until days before death. Penny-wise and pound-foolish medical insurance systems, including Medicare, continue to be stingy about physical therapy while lavishly reimbursing $6,000 ambulance rides and $7,000-a-day intensive care units for people who fall because they didn’t get physical therapy. That system needs to be turned upside down, so that it better rewards practitioners who take time and put patients at the center of concern.

As it stands now, it takes enormous gumption, savvy, support—and luck, and sometimes money—to find the way to a peaceful and well-supported passage.

From The Art of Dying Well: A Practical Guide to a Good End of Life by Katy Butler. Copyright © 2019 by Katherine Anne Butler. Reprinted by permission of Scribner, an Imprint of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

ILLUSTRATION © GARY WATERS

Katy Butler

Katy Butler, a former features editor and staff writer for Psychotherapy Networker, is the author of two award-winning books about aging and living meaningfully in life’s final quarter, especially in relation to modern medicine. Knocking on Heaven’s Door (2013) was a New York Times Bestseller and Notable Book of the Year. The Art of Dying Well (2019) is a road map —practical, medical, and spiritual —through the significant passages of life after 55. Katy’s groundbreaking work for the Networker was nominated for one National Magazine Award and contributed to several other NMA awards and nominations. Her writing has also appeared in the The New Yorker, The New York Times Magazine, Tricycle: the Buddhist Quarterly, Scientific American, Best American Essays, and Best American Science Writing. Other honors include first-place awards from the National Association of Science Writers and the Association of Health Care Journalists; a “Best First Book” award; and a finalist nomination for the Dayton Literary Peace Prize. She lives in northern California and loves to dance in the kitchen to Alexa with her husband Brian.