Enjoy the audio preview version of this article—perfect for listening on the go.

My family wants me dead.

I don’t know why.

They have a contract out on me with the nursing staff.

I think I’m going to die.

Four years ago, I lost my mind. It’s not like losing your keys or your kid in a store: you notice when you’ve lost them and try like hell to find them. This loss I didn’t notice. I just woke up one morning and it was gone. My self was there, but my thoughts collided with each other. It was as if all the pieces of an intricately assembled puzzle went flying apart. When I tried to put them back together, the configuration was off, and I wandered away and left it unfinished.

It started when I crash-landed into a perfect storm of forces that knocked me off my bearings. First, I’d contracted a severe urinary tract infection that had gone undetected for so long it resulted in delirium and confusion. Second, I was taking pain medication for two badly arthritic knees that were scheduled for replacement in the next few months. Third, a doctor added anti-inflammatories to my lineup of medications—which, combined with the lithium I’d been taking for 20 years without incident, rendered me lithium toxic, triggering still more delirium and confusion. Plus, I was anxious about my upcoming surgeries, and still reeling from the precipitous end of my 43-year marriage to a fellow therapist.

One evening, my daughter, Keara, discovered me on the bathroom floor, profoundly weak, with shallow breathing and significant confusion. I was immediately transported by ambulance to a general medical floor at a local hospital. Within 36 hours, I’d become manic, and then had crashed into a severe depression. Abruptly, I was transferred to the psychiatric unit—in the middle of the night.

The Nightmare Begins

“Why am I here?” I ask a nurse in the hall. “This isn’t where I went to bed last night.”

“Why do you think you’re here?”

Wait a minute, I think. I don’t play that game. But I’m too confused and scared to say it out loud.

“I don’t belong here. It’s my knees that need surgery. I have to leave.”

“That’s not possible. Go to your room.”

“I need to call my family to get me out.”

“Your family put you in here. Go to your room.”

I hobble to my room, where I find my purple suitcase on the bed. What is this doing here?

I open it up. Everything is organized, laundered, and folded perfectly, so I know that I didn’t do it. My sisters must have packed me up. They put me in here. I shiver. What could I have done to them? They must hate me and want to get rid of me. What better way of dealing with me than to get me locked up on a psych unit? I’m already a recidivist anyway, having been hospitalized three times for severe depression.

This time, my sisters must’ve cooked up something nefarious with the nursing staff. It’s the perfect plan: people who know about saving lives would know a lot about ending them. I don’t know all the details, but I know enough to distrust everyone here.

Beliefs Gone Bad

For two weeks, I suffered a full-blown persecutory delusion. Textbook. Still oriented to time, place, my relationships, my preferences, and my cognitive abilities, I was ferociously attached to the belief that I was in jeopardy at the hands of my family and the staff of the psychiatric unit where I was imprisoned. But I never told a single person what I thought. It was too dangerous.

What I understand now is that unlike rigid beliefs, psychotic delusions don’t budge, even in the face of the best evidence to the contrary. I didn’t even think about my thoughts. They were no different from all the other ideas I had that were woven into the fabric of my being. Reality doesn’t need to be analyzed. It just is. I never considered that there were alternate explanations for what I was observing and believing. Why would I? Delusions are embedded in the unquestioned essence of a person’s thinking—as true as ocean, ground, and sky. Not open to interpretation or reflection, not explained by any religion or cultural system.

Who Owns the Truth?

Delusions have always been of great interest in the field, but they’ve proven difficult to study and treat. In the presence of other forms of pathology, such as schizophrenia, the neurobiological component is often treated with antipsychotic meds. In less severe cases, they’re sometimes treated with cognitive therapies that target rigid belief styles, like jumping to conclusions, attributing all events to external sources, and misperceiving the intentions and behavior of others.

Although some delusional thoughts clearly pose a danger to the person or others around them, most don’t translate into violent behaviors. And if they aren’t causing a person distress, they’re unlikely to be disclosed and addressed any more than any ego-syntonic thought about the world. In fact, delusions are thought to be so common that the word delusion has broadened from the psychiatric nomenclature to the social, political, and cultural realms, in which, these days, the biggest and most heated question seems to be, “Who owns the truth?”

In my therapy practice in Washington, DC, I saw several clients who worked for federal organizations and flatly told me wild things about our government’s secret workings that left me wondering if they were clinically delusional or just speaking the truth in a safe, confidential setting. Both possibilities made me anxious. After all, especially when we do our job of meeting clients where they are, the “truth” can be scary.

Fine lines abound. Clinical delusions, for instance, are commonly sorted into two categories—bizarre and nonbizarre. But when it comes down to it, this differentiation is as ridiculous as other laughable terms in our field, like uncomplicated grief.

Supposedly, nonbizarre delusions are ones that the therapist can—maybe, maybe, maybe—imagine happening. Take my first teacher on the subject, Maya, a woman on my psych unit during my first hospitalization. She was on the other side of a full-fledged psychotic episode and open to my questions about her absolute conviction that she was going to marry Muhammad Ali. In her delusional state, she’d been convinced that Muhammad Ali had been conveying his ardor for her telepathically in every photo and video she had of him. At one point, in an episode of mania, she’d launched into full-scale plans for their wedding, which had culminated in purchasing a wedding dress and modeling it for her husband.

Unquestionably, this is a case of clinical delusion. But is it of the bizarre variety? Maybe not. It’s remotely possible—however staggeringly unlikely—that telepathic communication had transpired between Maya and the boxing legend. But if she’d believed, let’s say, that as a show of love she’d swapped out all of Muhammad Ali’s internal organs with her own, that is demonstrably impossible, rendering her delusion officially bizarre. My point is that a therapist would have to have a very open approach to the universe to fail to see either of these scenarios as bizarre as hell. To a great extent, bizarreness, like the truth, is in the eye of the beholder.

The usual stuff of our work as therapists is cognitive distortion. We help people identify their faulty beliefs—I’m a failure, or I’m always right—and replace them with ideas that are more consistent with living more functional and satisfied lives. But we need to be careful here. As therapists, how do we know a client’s beliefs are actually distortions? Are we just trading our own distorted beliefs for theirs? As trained arbiters of sanity, we’re also full of our own unique takes on reality that influence our work.

I was constantly reminded of the power of the therapist’s belief system in postdoctoral supervision with my mentor, who was a generation older than me and had a very different worldview through which he filtered interpretations of patients’ thoughts and behavior. He was buttoned-up in his evaluation of what constituted “normal” behavior, while I had a considerably higher tolerance for behavior he deemed pathological. My casual presentation of several young women’s sexual explorations, for example, was typically met with more alarm about me than them.

Often, as I described my latest case, he’d start to look alarmed, lean forward in his chair, and exclaim urgently, “Oh God, tell me your countertransference isn’t out of control, again?” We’d spend the rest of the hour exploring how I was more out to lunch than my client. His unsettling reactions made me careful about applying my own personal templates when I differentiated “sane” from “crazy” in my work.

But then, I had the lived experience of not being able to differentiate the two. I had to fall down that particular rabbit hole myself to understand the intense, alien power of delusion—to learn what it’s like to lose your mind, and what it takes to get it back.

In the hospital, I make notes to keep from screaming.

Oatmeal Poison. I don’t eat their food here. They are suspiciously eager to get me to eat. They pick out my meal and monitor me. I smush the food around. This breakfast has little brown flecks in it. There’s no way I’m dying over a bowl of oatmeal. When they look away, I do a quick scrape into my napkin and stuff it into the pocket of my jacket.

There’s a bowl of granola and fruit bars in the kitchen. I boost a bunch of them every time I pass by. There are also juice packs, boxes of dry cereal, and those awful fake orange cheddar crackers. They’re like money. I’m rich in prepackaged food.

The Fog. I spend a lot of time looking out the tiny window in my room. It’s covered with a thick mesh so I can’t escape or cut myself. I never noticed before that the whole hospital is surrounded by a moat. There’s a plaintive foghorn in the distance. It sounds out some kind of melancholy code. At night, waiting for what might happen in the dark, it’s all I hear. It sounds like crying.

My 93-year-old mother lives less than five miles down that road—I could walk to her—but it might as well be 5,000 miles. Her intellect, her will, and her fierce love have been enveloped by a thick fog that threatens to engulf her entirely. She was always my “mother barracuda” in protecting even her grown children. She would save me. A physical pain consumes me as I realize that she can’t save me now.

Student Nurses. Nervous young women dressed in short, white coats are on the unit. They cluster together like chirpy birds until a staff member introduces them as student nurses and asks us to “share” with them. I’m not sharing shit.

I stay in the day room because I’m less likely to be attacked here. I sit with two lovely old women who’ve been here forever. They’re just going to die here. Like me. We are the Stepford Patients.

Out of the corner of my eye, I see a student nurse tentatively sit down. “Tell me about yourself,” she starts off. Oh, honey, that may be the way to start a job interview or a pickup in a bar, but you’re not going to get anywhere here with that opener. I don’t say it. I shrug. This whole charade is starting to get on my nerves.

She asks what brought me to the inpatient unit. I have to suppress the urge to say, “An ambulance.” I throw her a bone and say that I’m depressed. She brightens up and looks ready to go the distance, but I’m stuck on the question about why I’m here. I don’t know what I did. I don’t know how I can make it better. Isn’t there anyone who will tell me?

I’ve noticed that all the students carry these big bags with logos. I watch them sitting with the other women. They have jars and bottles. Lotions and cotton balls. Oh my God, they aren’t student nurses! They’re student cosmetologists! What a scam, I think.

Protection. I attend every possible group. If I stay in a crowd, I’m safer. The staff, who are in cahoots with the family members trying to kill me, aren’t going to make a move on me in front of other people. In Process Group, I sit between the two biggest, scuzziest guys on the unit. I know one of them has explosive personality disorder, and they both look like they’ve seen their share of booze, drugs, and violence.

About 20 minutes in, the leader, who acts like the Queen of Empathy, asks me if I’d like to share. I hate that word. I answer, “I don’t know what to say.”

She leans in closer. “Why are you here?”

I’ve been here six days and I’m getting really tired of that question. “I guess I’m depressed,” I answer.

“Do you know why?”

“Well, my husband left me.”

One of the guys perks up. “How long were you married?”

“Forty-three years.”

This interests the other guy. “Why did he leave you?”

I feel ashamed to admit it, but it’s true. “He said I wasn’t fun.” I feel a rumbling on both sides of me. And, as if they’d practiced it beforehand, they slam the table and yell in unison, “Fuck him!” I register the warmth of spontaneous caring and I could cry. I’m sticking close to these guys. They might keep me safe.

Bed. I ease myself onto my bed. It’s low and unwelcoming to these poor knees. I get a cramp in my leg and twist in pain. An alarm from under the bed screams and brings three staff members running, “What’s going on?” I demand.

While two of them fool with wires under the bed, the other one responds very casually, “Oh, it’s just that with your bad knees, if you try to get up in the middle of the night, you might need help.” Yeah, right.

Dorothy. I don’t know why, but I keep thinking about Dorothy Gale from The Wizard of Oz. Dorothy was a wimpy, whiny farm girl with a yippy dog. If she’d really thought it through, she would’ve recognized that Toto was responsible for 75 percent of her troubles. What a stupid girl, I think. But then I recall how she had to fight off that cyclone, and how she didn’t make it home in time. She got shut out of the storm cellar. Everyone she cared about was in there. They were all together and safe. Except her.

She gets whacked on the head and all of a sudden, she’s wearing a pair of ridiculous red shoes with silly white anklets. And she has no idea that she’s just made the greatest enemy of her life, who’ll terrorize her through an endless journey that just gets harder with time.

The Helicopter. I know how to keep myself safe during the days, but the nights are interminable. It’s like I have to climb the long stairs to the gallows and stand forever with the rope around my neck, only to have my execution delayed again and again.

Every night between midnight and 1 a.m., I watch the shoes go by through the illuminated crack under the door. By now, I’ve matched the night shoes to the ones I see in the day. I know who they are, my assassins.

As soon as it’s dark, I hear the distant thunder of whirring helicopter blades. I listen, trembling, as the helicopter hovers for what seems like forever and finally sets down. The blades slowly quit their rotation. I know the plan. They’ll wrap me in a blanket. They’ll drug me, then shoot me or stab me or suffocate me. It doesn’t really matter. They’ll steal my life from me, and I’ll die never knowing what I did to deserve it. They’ll drop me in the Chesapeake Bay, which ironically, has been the site of so much enjoyment with the people I’ve loved.

But every night, something goes wrong for them, and their plan falls apart. It’s too windy or rainy. The helicopter is low on fuel. There are too many of them weighing the thing down, and the copter can’t land. It hovers for up to 20 minutes before they abort the mission. The voices bounce back and forth, suggesting, complaining, blaming. Eventually, the motor cuts out. As I hear the conversation drone on about what to do next, I pray to my dear departed father to watch over me as I traverse the hell of the coming hours, whether I’m saved or sacrificed.

At six o’clock each morning, I awake to a constricting blood pressure cuff on my arm. The nurse hates me. “Good morning, Miss Martha. Did we have a good night? After I take your vitals you can go back to sleep.” Take my vitals? Isn’t that what you’ve been trying to do ever since I got here?

It’s another morning: I’m alive. At first, it was a relief. Now, as she fumbles around for my pulse, it’s wearier: Okay, I’m still alive.

Keara. Keara comes for visiting hours, laden with Big Macs and a bag of new clothes. New clothes? Why would she buy clothes for a mother slated to die? Still, she’s my last, best hope. I inhale my gift from McDonald’s. It is transcendent. We make small talk.

I need to find a way to tell her that she’s got to get me out. “I’m doing really well,” I say.

“That’s not what I hear,” she says gently. “You’re getting better, but you’re still sick.”

“I’m not still sick. I never was sick.” Calm down, I warn myself.

“You need to stay here for a while,” she tells me.

Oh God, no. I was wrong. She’s taking their bullshit. My child, my only child. We’re so close. How did they get to her?

“Mama, you look so sad.” She reaches for my hand.

I stretch my arm out across the table, put my head down, and look up at her. “Keara,” I plead, “you know me. You know me.” I try to communicate with my eyes and transmit my desperation for escape. “Please.”

“Give it a few days, Mom. You’ve been so sick, but you’re getting better.”

Oh, Keara, my sweet girl, please, no. . . . She’s in on it.

About Dorothy. The Wizard of Oz is actually a vicious book that’s the stuff of nightmares. It’s the story of aching for what you had and somehow lost. It’s about the pain that drives you through one awful challenge after another, battling threats your waking imagination could never have constructed.

Never mind the evil witches. Never mind the horrible trees that chuck apples at hungry, unsuspecting victims, or the militias of winged monkeys, or the poisonous poppies, or the lying wizard. They were nothing compared the scariest thing of all—never ever recovering the anchorage of home.

It’s the story about being separated from people who have rooted you, for your entire life, in love. Auntie Em and Uncle Henry don’t just inhabit a home—they are home. Where’s my home? Where do I belong?

Last night. One of the nice nurses tells me I’m being discharged at 10 o’clock tomorrow morning because I’m doing so much better. My improvement probably magically coincides with my insurance limits, but I wonder how this will work out with my family, who must be pissed off by the staff’s ineptitude in offing me. Knowing my barracuda sisters, they’ll demand a refund. But I don’t give a damn right now because I’m going to be free. I just have to get through one more night.

After watching three episodes of Magnum, P.I. in the day room, I head off to bed. I stop at a card table set up across from my room. A guy in perfectly pressed scrubs and a short white coat sits behind it, stacking folders and organizing my meds. I say, “Are you new?”

“No,” he smiles. “I’m an independent contractor.” He tells me he has my medications ready. One by one, he names each, and I swallow it. But then he mispronounces Seroquel—twice. I look at him strangely, and he looks back. We have a stare-off, during which I become uneasy. He adjusts his white coat so that I can see the pens—and the shiny scalpel. I feel sick.

“I don’t want any trouble from you,” he warns.

I hear him give sleeping medicine to the women down the hall. In a soothing voice, he encourages them to have “sweet dreams.” Several hours elapse. I freeze when I hear him coming toward my door. I can’t believe that after surviving all this time, I’ll die on my last night.

But then a light comes on down the hall. It’s probably Mr. Baxter, who has to pee all the damn time. A nurse runs down to help him, and the contractor bides his time until everything quiets again. Then, thankfully, another light goes on. It’s Mr. Lewis, another prostate-challenged patient. He and the nurse take forever. The hall quiets. Then one of the older ladies has to go. She’s wide awake and kills time chatting up one of the aides. It goes like that for three hours. Urination is going to save me, I think.

Through my small window, I finally see shards of sunrise. I hear the card table being folded up and cleared out of the hall. I stay alert and absolutely still in my bed until the 6 a.m. nurse comes in. You want my vitals? Well surprise, surprise, you can’t have them, I think. I wish I had the guts to blurt it out loud, but I’m not taking any chances.

Escape. When Keara arrives to pick me up, I’ve been sitting on my bed with my packed suitcase for two hours. I don’t know if the people in my family have forgiven me and commuted my death sentence, or if this is just a respite. Right now, I don’t care. I have to keep my mouth shut and not let on that I know what they’ve been up to. It’d be dangerous. I’m scared that the nursing staff is going to hire people to track me down and kill me at my apartment. I’m going to have to hire security without Keara knowing.

Keara takes my suitcase. As we move toward the door, a nurse calls out, “Wait!”

Oh my God! Nabbed!

I keep going, but Keara stops. “We forgot the forms.”

Forms? Are you serious? I want to scream. The nurse tells me that patients’ evaluations improve the quality of care. Are you fucking kidding me? I don’t even look at the questions. To be safe, I just circle the middle choice. In the comments section, I want to write, “You suck at murder!” But the line between what I think and what I say has to stay firm. I may be leaving, but I’m not safe.

Several staff members accompany us down to the car. Every second is a minute. I immediately lock the doors and roll up the windows, even though it has to be at least 85 degrees outside. Keara fumbles around for her keys and slowly approaches the ignition. I can’t stop myself: “Step on it!”

From the look on her face, I know she’s unsettled. I have to remind myself that she was one of the conspirators in this nightmare, that she still has the power. “It’s just that I can’t wait to go home,” I assure her, and then keep quiet for the ride home.

Doubt. I can’t stand still in the elevator. The apartment is like technicolor. I touch everything, like it will ground me. My room . . . my room. Hydrangea blues and sea greens. Piles of dirty laundry and bills.

I tell Keara I feel strange. She says, “Mama, I don’t think you know how sick you’ve been. I don’t think you remember a lot of it. You’re getting better. Really.”

With time, my infections clear, my lithium level normalizes, and my regular medicines kick back in. My recovery culminates with the return of delusion’s nemesis—doubt. It nudges me into uncertainty about my hard, bold thoughts. Is there really a moat around the hospital? Wouldn’t I have noticed it before? And those brown flecks in my oatmeal—were they poison or cinnamon? And student cosmetologists? What was that about?

I’m confused. I need to know the biggest, hardest truth. I get up my courage and tell Keara there’s something I need to talk to her about. She looks afraid. “Keara, why does everyone in the family hate me? Be honest.”

“Mom, no one hates you.”

“No, really! What did I do to everyone that was so horrible?”

“You have to listen to me. You haven’t done anything to hurt anyone. We love you, and we’ve been so worried.” I see the honesty in her, and I hold it up against the fear in me. She wins.

I hunch over the table and what comes out of me are more than sobs. They’re moans. They’re weeks of a weight that came close to crushing me. They empty out all those spaces in me that have been crammed with terror and confusion. “But it was so real,” I tell her.

Kansas. When Dorothy finds her way back to Kansas, she’s desperate to share her story with Uncle Henry and Auntie Em. When Uncle Henry tells her that they’d been so afraid that she was going to leave them, Dorothy insists, “But I did leave you . . . and I tried to get back for days and days. It wasn’t a dream.”

Auntie Em tries to soothe her, “We dream lots of silly things.”

“No, Auntie Em,” she insists. “This is a real, truly live place, but there’s no place like home.”

Home. You tell them, Dorothy! Tell them how we can be catapulted into strange, dangerous places. How we yearn for the people we left behind. How we travel the vast and unfamiliar circuitry of our minds to rediscover our true place in the world. How we’re cranky and kind. Weary and hurt. Terrified and bold.

Yes, the passage of time and a pair of ruby slippers (or a handful of pills) helped deliver us. But mostly, it was the teeth-gritting odyssey we traveled on our own—our fierce, unwavering struggle to reclaim love and home—that returned us to safety.

And we are home, Dorothy. It doesn’t matter what anyone says. What happened to us was real. It will always be true . . . if only to ourselves.

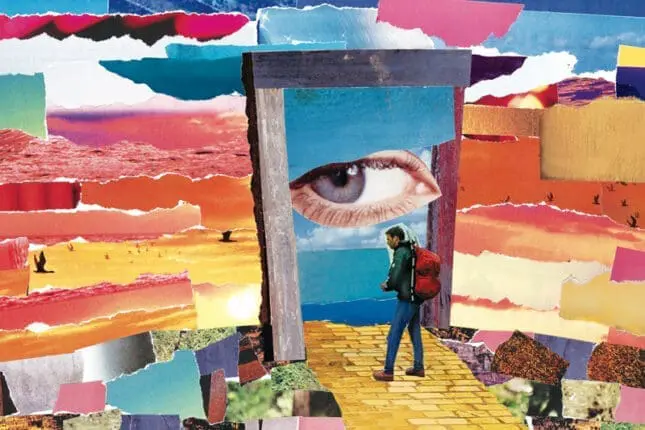

ILLUSTRATION © ILLUSTRATION SOURCE/DAVID C. CHEN

Martha Manning

Martha Manning, PhD, is a writer and clinical psychologist who has written five books, including Undercurrent: A Life Beneath the Surface. She has published frequently in the Networker as well as other magazines.