This article first appeared in the May/June 1996 issue.

At 14, Malik is nearly full grown. He bops into his first therapy session dressed in jeans so baggy that two of him could fit into them, with a 3-inch black belt that doesn’t do anything to keep them from riding so low that they could fall off at any moment. He’s here because he has been suspended from school for talking back to his teacher. As he slouches in his chair and looks bored, I sit with the team, observing the session through the one-way mirror.

Valerie, the therapist in the room, is a white woman in her early thirties, one of my trainees. Because Malik is African American and dressed in the uniform of his generation, I worry that Valerie will automatically experience him as menacing. As she closes the door, I can already sense how her discomfort pervades the room. A fine therapist, Valerie is clearly more guarded and tentative than I’ve ever seen her. Later, she denied she was afraid of Malik then added that she was never comfortable with teenagers. When we discussed it further, she said she worried that admitting to being afraid of a 14-year-old African-American boy who hadn’t done anything but slump sullenly in a chair would mean she was a racist. This is a problem many of my white colleagues and trainees encounter: when is their fear justified, and when is it the noxious fallout of racism?

Malik describes his unhappiness in school, telling the therapist, “You can’t trust the Man,” and “They’re out to get you.” He is speaking in code, raising the issue that is foremost in his mind, yet Valerie is reluctant to pursue it. She keeps asking him general questions about his life, ignoring his many allusions to racism. At one point, Malik makes a reference to the O.J. Simpson trial: “I grew up hearing about two things you don’t do,” he tells Valerie, “you don’t mess with the Man’s money, and you don’t mess with the Man’s women.” After confirming that Malik is referring to whites, Valerie carefully replies, “Yes, I guess some people do have trouble with interracial couples.” Malik suddenly becomes very alert and asks her, “What do you think?” Startled, she answers, “What I think isn’t important. People think different things.” But Malik insists on getting an answer. “No I’m asking you,” he says. “What do you believe?” When Valerie says she has never thought about it, Malik persists. “I guess I probably wouldn’t want a son or daughter to date someone black,” she finally tells him. “But it’s not because of what you might think. It’s just too hard, given the way things are.”

“I’m glad you said that,” Malik tells her, looking directly at her, sitting up straighter, his voice louder, “because this is how you white people feel. Only, you don’t want to be on the up and up about it. So I got to walk around feeling like I’m fuckin’ crazy.” Behind the mirror, none of us seems to breathe, each of us wondering if this session is about to get out of control. I am torn between wanting to jump in to “rescue” Valerie and wanting to let both her and Malik learn from each other. I’m not altogether sorry the conversation has taken this turn: the issue of race is definitely out on the table now. Malik and Valerie need to address it head-on. But the problem is, Valerie is uncomfortable not only with the topic, but with the vehemence of Malik’s expression. As he seethes with pent-up anger, Valerie’s response is, understandably, to divert it to something safer. I see this a lot when I supervise white therapists working with African-American clients. Like Valerie, they often try to change the subject. “Malik, let’s talk about what happens in school,” insists Valerie.

“I DON’T GIVE A FUCK ABOUT SCHOOL! DO YOU UNDERSTAND ME? I DON’T GIVE A FUCK ABOUT SCHOOL! I DON’T GIVE A MOTHERFUCK ABOUT SCHOOL! FUCK SCHOOL!!”

This is one of those tightrope moments in therapy, the pivotal seconds when the core issue, the raw emotion, is finally out there. I know it will be exhilarating to get to the other side, but I am also acutely aware of the danger of walking this line, how easy it is to slip. I decide to call in. “Valerie, I think you’re doing a nice job of getting him to express some stuff that he needs to get out,” I begin, trying to reassure her. “It’s like he’s throwing up now, and you need to let him. Try to empathize.” But I know it’s hard to empathize when the therapist feels threatened. I have done therapy with self-confessed “nigger-hating,” white teenagers, so I know when I can no longer be helpful and have to attend to the part of me that’s fearful. Still, being a good therapist means learning how to hold one’s own fear and focus on what the client needs at that moment. We have talked about fear in an abstract way in Valerie’s supervision, but this is her first experience confronting it in the flesh.

I watch Malik come to life as he screams out his frustration and pain. Although it churns up all kinds of emotions in the rest of us, I can’t help but think this is an important experience for him. Unfortunately, Valerie cannot stay with it. She wants what we all want when we feel threatened: control. “Look,” she tells him in a tight voice, “you’re entitled to feel what you feel, but I’m not going to tolerate you yelling in here.” Malik immediately shuts down, although I can see the rage still in his eyes. I worry that, as Valerie lays down the law and becomes the embodiment of all the put-downs and slights that he feels besieged by in a white world, his rage might suddenly shift to her.

Valerie has used her position to do what Malik believes whites always do: tell him to shut up, make him feel small, wrong and frustrated. At the same time, Valerie is now in a bind because the therapy has become a conversation about Malik talking more quietly. With teenagers, it is almost always a mistake to focus on issues of style take the hat off, pull the hood down, pull the pants up, sit up straight, take the headphones off, stop swearing, stop yelling. I have never found it useful to get into these stand-offs.

I call in again and ask Valerie if she is willing to take a one-down position now. Can she admit that she felt overwhelmed by what Malik has been saying, but assure him that therapy is a place where he can express himself in whatever way he needs? She tells Malik, “The team just told me what I was already feeling. I realized I got a little carried away when you were yelling. And yelling at you for yelling didn’t help. So let’s start over,” and she extends her hand to him as if to shake it. “Deal?” Surprised, somewhat reluctant, Malik nevertheless shakes her hand. Then she says, “It seems like your life so far has been about people telling you what you have to do. What is this thing about school?”

There is now a tone of genuine curiosity in Valerie’s voice. Malik relaxes for the first time and the session shifts. He talks about feeling singled out and persecuted by his teachers for being black. He feels he hasn’t done anything to deserve the treatment he receives. As Valerie listens to him fully, he is finally opening up to this white therapist who has invited him to talk about the ways his white teachers are screwed up.

Once Malik feels Valerie is, in some small way, on his side, she is able to challenge him a little about what he might be doing to contribute to the hostile tug-of-war at school. After Malik describes a confrontation with a teacher, she says, “So when you got up to walk out of the classroom to use the bathroom, and you ignored the teacher when she asked you where you were going, what would have happened if you had just said, ‘I’m going to the bathroom?'” As they talk, he defends his position. At times, he tells her, “You don’t understand. You can’t understand.” Maybe this is true, but maybe her questions also sink in and give him some options he can try next time he feels helpless to change his teacher’s attitude toward him.

With adolescents, I treat every session as if it is the last, and try to make the greatest amount of impact I can while they are in my office. At the end of this session, I don’t know if Malik will come back again. But my guess is he will because he took away some connection to Valerie, some sense that she understood him.

THERAPY WITH TEENAGERS HAS TO be about creating, and then holding, a connection. As a therapist, I am like a spider trying to lure my adolescent clients into a web that will support them. First, I work to spin a strand of connection between us, and when that is established, I focus therapy on strengthening or reconnecting the teenager’s bonds to his or her family, school and community. It is when teenagers lose their connection to these sources of support that they are most at risk. Everything in their worlds becomes one-dimensional, and all that matters then is their pain and the relief of it. These cut-off kids become the ones who are capable of staring you in the eye and pulling the trigger with absolutely no remorse, and even some inner thrill.

Adolescence is a time of life when teenagers define who they are by trying on different identities, like trying on shoes and discarding the ones that don’t fit. But if you are a black kid in an overwhelmingly white society, you have fewer opportunities to try on different identities or even to define yourself because you are constantly grappling with society’s blanket definition of you as, first and foremost, black. Being devalued as a person of color means being drained, every day of personal dignity, respect, validation and one’s sense of belonging. Under a barrage of countless, and recurring, negative images and messages about black people, many African-American teenagers find themselves in a trap: how can they forge a positive identity the developmental task of adolescence without having a positive racial identity, and how can they cultivate a positive racial identity in a racist society?

A black 15-year-old young man knows that when he walks into a store, he will be followed suspiciously by the manager, no matter what he is wearing, how much money he has in his pocket, what grades he gets. His blackness is the first, and sometimes only, thing that most of the whites he encounters will either see or care about. He is put into a slot that links him with drugs, guns, violence, crime, jail. If this 15-year-old has chosen to dress in the fashion of the times the baggy jeans, the baseball cap turned backward he will almost certainly be assumed to be a gang member, a menace to society. While white teens his age can dress in the same clothes and be regarded by the white adult world as “going through a phase,” black kids are less likely to be given the benefit of the doubt. A white teenager might skip school, steal a car, get into trouble with the law, but then settle down and work hard in school because he wants to get into college. While white kids have this freedom to make mistakes and then get a second and third chance, the stakes are much higher for African-American youth. Making the mistake of getting into trouble with the law or getting a bad reputation in school is much more irrevocable because there is far less latitude for failure.

Therapists who work with these kids have the task of holding the racial context of the teenager’s life in front of them like a pair of glasses, without making race the sole explanation for why people are the way they are. In the case of Malik, his therapist’s job is not to assess whether the teacher was picking on him because he is black or because he was simply frustrated by a kid with a bad attitude. The therapist’s job is both to support Malik and underscore the legitimacy of his feelings about racism, while also challenging him and holding him accountable for his own actions. Both pieces need to be there, or racism can be held up as an excuse not to try, or it can be ignored and minimized, fueling Malik’s rage even more. While I try to use the context of racism to help African American teenagers understand their situations, verbalize and vent their feelings about its effects on their lives, I also want them to develop inner resources and tools for handling the adversity they face in more useful and productive ways. Some kids have to learn to develop a stronger shell when the world looks down on them for being black; others have to find drastically different strategies for handling conflict, hurt feelings and rage if they are to avoid self-destructing.

Fifteen-year-old Terence was referred because his parents, particularly his mother, were concerned about his behavior. She described a free-floating anxiety about her son, how she was afraid he was running around with the wrong crowd, that he wasn’t getting as much out of school as he could be. While Terence’s older sister was on her way to college, the mother complained that her son seemed set on a track of failure. He had been suspended from school several times for mouthing off to his gym teacher, and he had been warned that he would be expelled if he was suspended again. His mother said, “Life is tough for young African-American males. There isn’t going to be anyone out there waiting to give him a hand-out. He’s going to have to prove himself. He can’t afford just to be average.” But as his mother talked, Terence looked at the ceiling and rolled his eyes. He had heard all this before.

While Terence listened to his parents respectfully and was always soft-spoken and polite in therapy, his teachers’ reports described a different kid. “It’s not always what he says, but his demeanor that seems so hostile and harsh,” wrote one teacher about him. Terence never argued with his parents in therapy, and, in fact, one of the most difficult sessions was when we tried to get him to give his mother some feedback about how he felt about her constant scrutiny. He was filled with trepidation when he finally told her how he felt because he didn’t want to hurt her feelings. The focus of Terence’s rage, as it often is with black teenagers, was outside the family. “That gym teacher yells at me like I’m a dog because I’m black,” he would say, defending the actions that had landed him in trouble in school. His mother would always take the position, “That’s the way life is. Sometimes you have to turn the other cheek. Just because he’s ignorant, Terence, doesn’t mean you have to be.” But Terence’s father would tell him, “I’m proud of you for standing up for yourself.”

Once his parents’ mixed messages were out on the table, I addressed them by asking the father to talk about what it was like for him as a teenager, telling him that he had important lessons from his own experience to pass on to his son. I have found that it can be hard to convince many African-American parents that they need to talk about their own encounters with racism. Terence’s father felt I was asking him to expose himself in a humiliating way that would make him lose face with his son. His mother was willing to talk about her experiences, and described being a little girl and watching her mother be harassed by a white police officer in Alabama. “It was ugly,” she told Terence, “and I didn’t know if we would be alive to see another day, but I learned that you don’t fight ugly with ugly. You have to be better than they are.” Terence nodded as he listened, taking in her story and also her philosophy of dealing with hatred.

Hearing his wife’s story released something in the father and he began to tell his own story about his first experience in an integrated school and how the white students had called him dirty names. Terence paid close attention, hearing for the first time about his father being harassed for being black. “So what did you do?” he asked his dad. His father looked vulnerable and sad for a moment as he described one of his tormentors throwing an orange at him in front of a group of others, who laughed. “I didn’t want to go back to school the next day or ever again,” he said.

“Well, did you?” Terence asked, leaning forward. His father nodded. Terence was shocked. “You did? You went back?” His father looked at him and said, “When you get knocked down, you have to get back up again. You have to keep trying. You can’t let white people get the best of you.” Then he talked about the day he returned, how he was harassed again, and then he finally beat up one of the boys who was teasing him. I wasn’t as pleased about that part of the story, and the fact that the father told it with some gusto. I asked him if he would still handle the situation that way this wasn’t the message I or Terence’s mother wanted the teenager to take from the session! The father said maybe he wouldn’t, but when your dignity is so hurt, sometimes you have to do what you have to do. “You’ll always be kicked around,” he said. “You can’t just lie there. You have to get up and dust yourself off and keep moving, know how to hang in there and survive. Just think about what would have happened if my father and my father’s father hadn’t gotten up?” Terence sat there nodding, absorbing his father’s story.

In the next session, the father reported how recalling that story revived a lot of old feelings of humiliation and he admitted, “Terence, I wanted you to respect me, not think that your dad was a sissy, so I threw that in about how I beat up the white kid. I don’t really want you to follow my example.”

There was some consolation, and maybe even some instruction, for Terence in learning that others so close to him also had to bear the burden of humiliation and injustice in their time. But Terence, like most teenagers today, needed more support than his parents, alone, could provide him. So I invited his friends a group he called his “posse” to come to therapy, despite knowing this would upset his parents. While I certainly understood their fears about his involvement with them, I regarded Terence’s posse as his other family, whether we adults approved or not. It’s my belief that parents who want to have an impact on a child who is involved in a gang or a group of friends can do it best by having some access to the friends. For a parent to set him- or herself up in complete opposition to the peer group is a recipe for impotence.

When Terence arrived for the next session with four members of his posse, I shook their hands and told them it was good to finally meet them and put faces to the names. Almost immediately, I saw a whole different side of Terence. Usually so laid-back and soft-spoken, Terence was now talking with animation. I asked the posse, “So, what is it like being in school? What happens?” I quickly heard about how they felt singled out and picked on. “What is the gym teacher like? Why does he do these things to Terence?” They told me, “Because he’s racist. He doesn’t like black people. That’s it.” I asked, “What is he like with other students?” trying to validate their feelings but also introduce the idea that this teacher might not be singling them out. Eventually, I challenged them: “How might you handle the situation differently? How can you handle it so it doesn’t screw you up? Why do you continue to play into this teacher’s hand? If he’s the type of person who is out to get you, why do you behave in the way that he wants you to?” I left the posse with this message, “You brothers have to be about the business of looking out for each other’s backs. If you see Terence about to go off, you have to help him out, not by jumping in, but by sending a sign to him to get control of himself.”

After that session, I heard a lot of criticism from Terence’s parents, even though I had called to let them know that I was meeting with the posse. I told them I was sympathetic to their concern, but what was our alternative? Fortunately, by this time, they trusted me enough to accept my judgment, and I continued to meet with Terence and his friends. The posse’s group project became keeping Terence from flying off the handle when his gym teacher did anything to provoke him. If a confrontation started to heat up, two things were supposed to happen: one of the friends would interrupt by raising a hand or somehow distracting Terence and the teacher; the back-up plan, if that didn’t work, was that one of them would rub the right side of his face, just below the eye, which was Terence’s signal that he “needed to chill.”

A year later, Terence is still in school. His parents and I are holding our breath that he survives the next few years. There has been one serious incident. One night, two of his posse stole the gym teacher’s van and then picked up Terence to go joy-riding in it. Terence and the others were arrested and fined. One boy with a previous record was sent to juvenile detention. “Terence is old enough now to know he’s African American and what that means,” says his mother with a sigh. “He’s struggling with that. I hope my son makes it.” My fear is that the line is too thin and it could break so easily. We could lose Terence.

Of course, the danger for Terence won’t simply disappear if he graduates high school. A lot of therapy is about helping him to imagine a life beyond age 20. Terence is a smart kid, and before his problems at school came to a head and he absorbed his posse’s contempt for education, he liked to read. I started giving him books to read by African-American authors that describe what it means to grow up black. Under great protest, he managed to read some of them. Lately, I’ve even seen flashes of ambition in him to be a writer. I always say to him, “I’m going to continue to stand behind you, and when I see you fall back, I’ll be here to push you up. I believe you can do it.” He is motivated by our connection and his strengthened bond with his parents. Even as it seems like he wants to float off like a balloon, we are his anchors. While he keeps challenging the adults in his life to give him more line, he gets his grounding by knowing we won’t let go of the rope.

While I worry about Terence losing his slim hold on school and becoming another drop-out, 16-year-old Jamal, whose parents divorced four years ago, has already taken that path. Growing up in a middle-class family in a mostly white neighborhood, Jamal is dangerously violent, sometimes using a knife, other times his fists, to express his intense rage. He dropped out of his mostly white school last year, and soon after was referred to therapy by the juvenile justice system after being convicted of assault. When I spoke to his mother, she was at a loss for what to do, or why her son seemed to pick fights just for the sake of fighting.

Jamal’s participation in therapy was court mandated, and initially he decided he wouldn’t talk to me at all. Instead, he would just saunter in, plop down in the chair, fold his arms and stare. Rather than trying to make him talk, I talked, usually about things I thought might provoke him: “I know you don’t want to be here or talk to me, but I’m not going to dis you the way you are dissing me. I’m real curious about what is going on with you, why you’re having all these fights.” If he adjusted his hat or swiveled his chair a centimeter, I attributed some meaning to it. “Oh, you didn’t like that idea.” This irritating style of monologue usually propels these clients into conversation, and it worked with Jamal.

“You think you know everything! You don’t know me!” he finally exploded. His participation in therapy always revolved around his anger and was always aimed at “them.” “They just want to build more jails. They won’t be satisfied until I’m behind bars somewhere,” he said one day. I challenged him, “So what are you going to do about that?” He glowered at me. “It’s not up to me,” he shot back. “When you’re black in this society, you don’t stand a chance. It’s like being born with two strikes against you. Everyone is just waiting for you to fuck up.” Jamal often talked about his desire to kill “them,” and I feared that it wouldn’t be that big a stretch for him.

Even though Jamal’s anger was the most noticeable thing about him, he also had another side, the side that made him cry while he was watching a talk show about racist skinheads and felt overwhelmed with sadness at people’s cruelty to one another. He was often teased by the black kids, who called him an “oreo” because he lived in a white neighborhood. Rejected on both sides, he felt enormous rage toward both white people and “fucked-up black people.” He felt he had no place in the black community and experienced an unbearable sense of alienation. Jamal had nowhere to go: at school, he had no one to talk with about his experiences as one of the only black kids; at home, his divorced parents were so caught up in their own busy lives that they had little time for him. Jamal had no friends on the street to hang out with in his white neighborhood. Gradually, over time, he came to believe that he was alone in his pain and always would be. He started to pick fights.

Searching for a way to get clients like Jamal to find a way to voice sides of themselves they can’t put into words, I often use music. “Why don’t you bring in your favorite rap song or some song that says something about you, who you are,” I told him, once he had stopped trying to freeze me out completely and would at least grunt a reply to my questions. “Bring it in and let’s play it next time, and you tell me how it’s you.” Jamal looked puzzled, as if I was crazy. But we shook hands on it, as though some kind of solemn vow was being given. The next week, he brought in a rap song that talked about race struggles. When I asked, “So why did you choose this song?” Jamal tried to blow me off. “Nice beat to it,” was all he would say at first. But when we went through it line by line, he told me how he connected to the righteous anger the rapper described, the powerful rush of physically striking out at people who hurt you and the pleasure of teaching them a lesson. I didn’t get into a debate about the way the rapper referred to women as “bitches” although I did challenge him on it a few sessions later but I stayed with the themes that were speaking so powerfully to Jamal. By the time we were finished, he had told me, through the song, what happened for him during a fight, why he needed to fight and also why he was in such pain.

What surprises me is that so often rageful clients teenagers and adults, both are almost completely inarticulate about what their anger is really about. Almost always, the roots under the tough exterior go back to loss, hurt and pain, most of it unacknowledged and unmourned. In the next session, Jamal and I drew a diagram charting the emotional and physical losses in his life. He was able, for a moment, to stand back from his life and take in the magnitude of the emotional freight he was carrying around. We charted the emotional loss of his father when his parents separated, his family’s frequent moves and his lost friendships. A first cousin who had been like a brother to him was lost to drug addiction. As I turned the conversation to other emotional losses around being devalued as a black man, Jamal could not find words to speak and I saw his lip trembling slightly. Then he shut down again and the walls came up. He reverted to something like the silence with which he had started therapy. He just sat, for almost 10 minutes, saying nothing.

But this silence was different from his initial, defiant refusal to talk. This silence was about his fear that we were getting too close to what hurt him the most. With my feet propped up on the table as I waited for him to speak, 1 wracked my brain to think of how to lead Jamal through this, and then the oddest thing popped out of my mouth.

“What do you think of these socks I have on?” I asked him.

“I don’t like ’em,” he answered, without hesitating.

“Okay,” I said, “I’ll take them off.” I took my socks off. Then I said, “Now, I’ve exposed myself. So, now, what’s it like being black?” And he answered me. Somehow, with my goofy question, my willingness to be playful and sit there with my bare feet on the table, I had unbalanced him. With a sadness in his voice that I hadn’t heard before, struggling to contain himself, Jamal told me that if he had a choice, he wouldn’t want to be black. It just hurt too much. I could see his lips tremble again as he spoke. I kept bringing his attention to it, “Tell me what’s happening for you?” He kept saying, “I don’t want to talk about it.” He had come far enough; he wasn’t ready to go any farther.

I saw Jamal for about six months, and in that time he didn’t get into any more fights, and even started making friends with a group of black kids. They still teased him about living in a white neighborhood, but he was able to handle it without flying off the handle. I spoke to him about self-hatred and what it looks like and how one needs to respond to it. I told him I thought that when the other black kids teased him, it was a manifestation of their self-hatred, too. And we talked about a type of joking African Americans do, called “the dozens,” a game of teasing and one-upmanship that is supposed to demonstrate verbal dexterity. The unspoken rule is: however devastating the put-down, it’s all in good fun to get a laugh at someone else’s expense. The dozens is a way African Americans inoculate themselves against cultural devaluation, a way of learning to hold the pain of ridicule and humiliation without losing connection to the community.

I don’t know what will happen to Jamal down the road. At the very least, our time together gave some breathing room to the suffocating force of his rage. My hope is that our conversations about anger, sadness and the struggles of being black in a society like ours created a connection he will be able to hold on to, and, perhaps, generated the possibility of a moment of reflection between impulse and action that, one day, could save a life.

So often, my white colleagues and students ask me whether it’s possible for them to forge a connection with African-American teenagers the way I can. Certainly, being black may give me an edge at first, when an African-American client first meets me and sees someone who looks like he does. But then I often find myself facing questions from my African-American clients about whether I am “really” black or black enough. Establishing a therapeutic bond is always a challenge, but I believe in the possibility of clinicians making a meaningful connection with clients across all our apparent differences. I have seen white trainees like Valerie negotiate the tortuous barriers of suspicion and fear to establish a bond of real trust with their black clients. Similarly, I have seen my black colleagues and students forge therapeutic connections with their white clients. This is not to say that differences are not challenging at times, even painful and scary, but they need not be an impediment to making therapy work.

Therapy is about healing and also about promoting connection. The healing starts when we lance the wounds our clients bring in, help them vent their pain and rage and let the toxins pour out. The more difficult part of the process is rooted in the bond the client feels with us. While that relationship can seem small and insignificant in the face of the devastating social problems that clients bring in, it nourishes the seed of hope from which all change grows. Ultimately, the impact of therapy depends on our making a human connection, but to make that happen we must overcome our fears and dive into the process.

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction or distribution is prohibited without permission.

Photo by Monstera

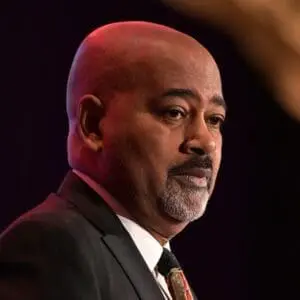

Kenneth V. Hardy

Kenneth V. Hardy, PhD, is President of the Eikenberg Academy for Social Justice and Clinical and Organizational Consultant for the Eikenberg Institute for Relationships in NYC, as well as a former Professor of Family Therapy at both Syracuse University, NY, and Drexel University, PA. He’s also the author of Racial Trauma: Clinical Strategies and Techniques for Healing Invisible Wounds, and The Enduring, Invisible, and Ubiquitous Centrality of Whiteness, and editor of On Becoming a Racially Sensitive Therapist: Race and Clinical Practice.