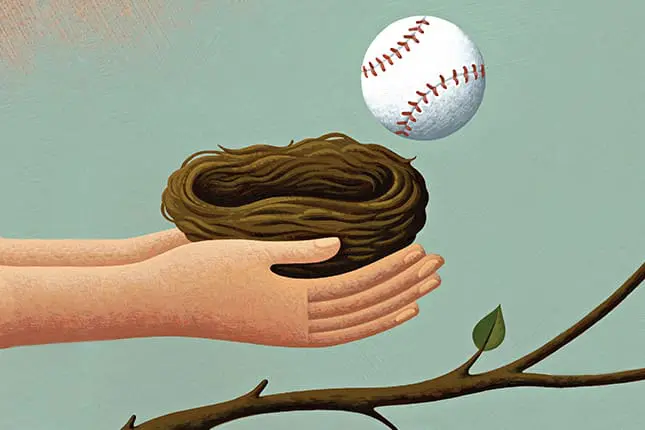

This is a story about change, loss, and a baseball game that I didn’t go to. It’s about the painful pleasure of having children prepare to launch themselves into the world, severing ties and—in some sense—leaving you behind forever.

Our youngest daughter has entered her final year of high school and is busily applying to college. My wife and I aren’t new to launching children—our eldest son has finished his undergraduate degree and has started a family of his own, and our middle son just began his junior year of college. While each of these takeoffs had its own, unique emotional trajectory, an important similarity linked the two: at least one child remained behind for us to parent, so my attention turned fairly quickly from feelings of loss to focus on the two, and then the one, still harbored at home. I managed the melancholy that came with the knowledge that the era of basement rock-band rehearsals, raucous Simpsons and Family Guy TV marathons, and impromptu, lawn-lacerating lacrosse games and wrestling matches was coming to its inevitable close. But this next looming departure, this concluding flight, brings up different feelings.

Jessica is my only daughter, and we’re very close. Despite being of different genders, it seems to me that we’re “built” the same way emotionally. Our sons were quite a handful in their early years: the first radiated a relentless energy, which required constant, creative channeling, and the second struggled through some worrisome medical problems and several terrifying hospitalizations. So we were taken aback when our daughter entered the world with a sense of calm—an emotional balance and integrity that we simply didn’t anticipate. Overall, there was an ease to raising her that was wholly unfamiliar, yet profoundly gratifying. Today, she’s smart, funny, sensitive, talented, and, although I’m surely biased, quite beautiful. Of course, this doesn’t mean that she’s perfect—she performs a clever and sophisticated vanishing act when it’s time for housework, displays an irrational panic when confronted with a harmless stink bug, and inevitably has a flat tire in whichever family car she drives. Nevertheless, she’ll leave a significant void when she marches forth into her future.

Last night, Jessica went shopping with her mother and me for the clothes that she’ll need for her upcoming senior-year internship. Walking up and down the department-store aisles, I couldn’t help noticing the hundreds of dorm-room items for sale, realizing with a start that at this time next year, those are the shelves that we’ll be selecting from.

As we browsed, I watched with fascination and curiosity the customers clustering around those shelves—parents like me, fitting out their young-adult children who are on the verge of their own lives. I’ve personally been stumbling through the wilderness of family life for more than two decades now, and have treated countless families in my practice. Yet, each stage of development remains endlessly intriguing.

This evening, the distinct choreography between parents and their emerging adults strikes me as particularly touching—these aren’t the distracted, impatient, overwhelmed mothers and fathers of crying infants or cantankerous toddlers, of fidgety children, or of sullen, snarky adolescents. By now, those relational rough edges have largely been smoothed out, and the parent–child dance has relaxed and softened, displaying a certain awkward grace. Yet it has a restlessness as well, a sense that this current equilibrium, pleasant and functional as it may be, is temporary—the world is beginning to tilt; the light is subtly changing. Both generations know it and sense it, and there’s absolutely nothing to be done about it.

When we arrived home, I checked the mail and discovered an envelope containing the proofs of Jessica’s high-school graduation pictures, taken several weeks earlier. I flipped through them and gasped at the picture of her in a cap and gown, smiling luminously, confidently holding the fake diploma. As parents, we all experience these startling moments—moments when we view our children through a different lens, and suddenly realize that they’re no longer who they were—which means, of course, that we’re no longer who we were. We live our lives struggling to deny our awful susceptibilities, until confronted with what we’re most susceptible to: the inexorable passage of time.

As I write, exactly one week of summer vacation is left before her senior year begins. This morning, I left my daughter a note before I headed out, suggesting that we go to a baseball game tonight, with or without any friends she wanted to invite—probably the last time we’ll be able to go before her final year of high school. When I called her at midday to ask whether she was interested, she politely declined, not sounding particularly intrigued. At the end of the day, when I came into the house after work, she informed me that she did want to go to the game (my heart lifted exuberantly), but not with me—with two of her friends.

“Is that OK?” she asked, her head tilting, birdlike, watching me intently, as she’s always done. How does one answer such a question? By this stage of life, every parent knows that there isn’t one answer, but two. The first is the one that you reveal to her, the one that’s short and kind and clean: “Of course it’s OK. Have a great time. I hope the Orioles win.”

The second answer is the longer one; the one that’s more accurate, but more devastating: “It’s certainly not OK. It’s not OK for you to grow up and leave me behind. It’s not OK for you to hurt me, even if you don’t mean to, even if you must—and I know you must. It’s not OK for you to shove me out of the bright center of your life and into the twilight of insignificance. It’s not OK for you to remind me that time doesn’t stand still, that there’s a distant drumbeat of mortality that begins to pound ever so slightly louder with each child that departs. The Orioles may win; but, tonight, all I feel is loss. No, no, no; it’s not OK!”

In every love relationship, there are the words we choose to speak to our beloved and the words that must remain unspoken out of love. We keep these words to ourselves, smile gamely as our children voyage forth into the world—just as we asked them to do, just as we taught them to do, just as we want them to do. And as they go, our hearts break a little, and our souls sink a little as we wave good-bye and watch their cars pull away; watch the red taillights grow smaller and smaller and then disappear in the dusk, until all that’s left for us is the yellowed moon, the tender breeze, and the wistful, wishful chirring of late-summer cicadas.

Illustration © Adam Niklewicz

Brad Sachs

Brad Sachs, PhD, is a practicing family psychologist and the bestselling author of numerous books for both professional and general audiences.