Clients often share ideas in session that can sound misguided, even outlandish. This has been particularly true over the past few years, with the rise of climate-change deniers, flat earthers, and conspiracists who believe Taylor Swift and the NFL are in cahoots to reelect a Democrat to the presidency.

Many therapists have been taught not to challenge these kinds of beliefs and simply view them as the client’s subjective truth. But what happens when these “truths” are so onerous to others that they result in rejection and isolation? Can espousing an unpopular or divisive idea become not just problematic for clients’ relationships, but worthy of an intervention?

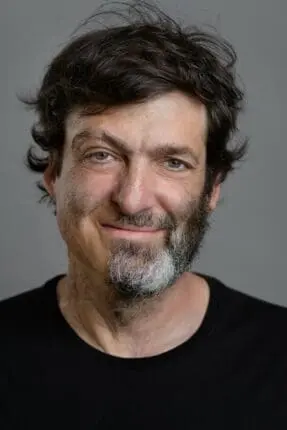

Dan Ariely is a professor at Duke University, a behavioral economist, and the author of the bestselling books Predictably Irrational, The (Honest) Truth About Dishonesty, and the recently released Misbelief: What Makes Rational People Believe Irrational Things.

Recognizable by his half-beard—the result of suffering traumatic burns over 70 percent of his body when he was 18 years old—he’s the inspiration for the NBC series The Irrational, about a crime-solving behavioral scientist and burn survivor.

Ryan Howes: How can we really know when a client’s beliefs about society are harming them? And what can we do about it?

Dan Ariely: I think the key is to discern whether their beliefs separate them from society. Are their beliefs making them more isolated? Obviously, the more entrenched their beliefs, the tougher it will be to help these people, but as a social scientist interested in behavioral change, I think it’s the therapist’s obligation to try to help them avoid the funnel of misbelief—because going down the funnel of misbelief is bad for them and bad for society.

RH: How do we as therapists know if it’s a belief that’s simply different from our own, or a true misbelief?

Ariely: A misbelief has two components. It’s both a belief in something that isn’t so, and it’s a perspective on life. The perspective on life is probably more important for therapists because it becomes a lens through which your clients may view everything else.

You can say, “My client believes the earth is flat. What’s the harm in that? They’re not going to change the curvature of the earth by thinking it.” But that’s usually not all they’re thinking. Somebody who believes the earth is flat also believes that NASA and the government are lying to them, and every pilot knows the truth. Their perspective is, “There are lots of people in on this lie, and for some reason they’re hiding it from us.”

With misbelief, the lens that people adopt has the potential to worsen and expand over time, like a funnel where one belief is an entry-point that gets wider and encompasses more. If you wake up in the morning thinking someone’s out there waiting to get you, then everything you see that’s not perfect seems like it’s for that reason.

The origin of this funnel of misbelief, which can attack our entire psychology, is stress. If we have high resilience to stress, we’re able to manage more of it. But when we’re thoroughly stressed, we seek a story to explain what’s going on, and it’s even better if the story has a villain. As our resilience goes down—and society now has low resilience, since social media has substituted casual friendship for deep friendship and there’s more economic inequality—we’ll see a bigger breeding ground for misbeliefs.

RH: How does “the illusion of explanatory depth” contribute to a misbelief funnel?

Ariely: In most cases, our confidence in our knowledge of things is much higher than our real knowledge. Take the example of a flush toilet. Do you understand how one works? Most people will say yes. If I ask, “How well do you understand it on a scale from one to 10?” Most will say, “Nine and a half.” But then if I say, “Great, here are all the pieces for a perfectly new flush toilet, please build it.” Nobody can build it. How well do you understand a flush toilet now? Not so much is usually the answer.

But how do we usually try to convince people they don’t know as much as they think they do? Usually, we argue with them. Maybe you talk and the other person talks, each for half an hour. What do you do in the time that you don’t talk? You want to say that you listen, but we all counterargue in our head. At the end of an hour, we’ve talked for half an hour defending our position, and then talked in our heads for the other half-hour, still defending our position. Our record of convincing people of anything this way is just not good. Ask arguers, “How many people have you truly convinced in the last three years?” They’ll say, “Nobody.” “How many times were you convinced?” “Not once.”

What can therapists do differently? They could say, “Help me understand your perspective better. How exactly are the elections stolen? How are elections actually tallied? How would a chip fit in a needle? Help me understand your view.” Then a client might say, “You know what? I don’t really know.” The challenge, of course, is none of us likes ambiguity. But embracing it is important.

RH: Are there warning signs we should look out for? Can we predict who’ll be most susceptible to a funnel of misbelief?

Ariely: One factor is personality: narcissists in particular have a higher level of stress when they don’t get positive reinforcement, and therefore they have extra motivation to find a story with a villain in order to deal with it. The social part is interesting, too. Research shows that when people feel ostracized, everything good about humanity goes away in their eyes. And once you feel ostracized, how are you going to react? You’ll look for new people who believe what you believe. When you find them, you’ll feel connected, and maybe want to make a name for yourself, so you’ll start saying more extreme things.

Another social component we refer to comes from the Hebrew Bible, which tells the story of two warring tribes, the Gileadites and the Ephraimites. Around 1370 BC, the two tribes fought a war, and the Gileadites prevailed. As the Ephraimites fled, the Gildeadites set up checkpoints along the Jordan River. If they didn’t know which tribe someone was from, they’d ask, “Hey, what do you call this plant?” Then they’d hold up the ear of a grain plant, which the Gildeadites pronounced shi-bboleth and the Ephraimites pronounced si-bboleth. If the stranger said shibboleth, everything was fine. If not, they were slain.

Did anyone really care about the name of the plant? No. They cared about your identity. So now we use the term shibboleth to describe a discussion that looks like it’s about the facts but is really about identity. Now ask yourself how much of the political conversation is really shibboleth.

The last big component is cognitive dissonance. The moment people invest a lot in their community, in posting things, in doing their own research, it’s very hard for them to admit that they’re wrong.

RH: In therapy, if someone says, “My father abused me when I was a child,” we don’t start an investigation to figure out if that actually happened. We take them at their word. We might say, “What did this mean to you, and what can we do about it?” But now we have clients coming in saying, “The sky is green,” and we’re being put in a different predicament.

Ariely: My guess is that if people shared difficult memories from childhood, it wouldn’t separate them too much from the rest of society. But if they believe in QAnon, the odds that their friends will stop inviting them out will increase. It’s more than just a subjective experience or difference of opinion: it’s isolating.

That people don’t talk about politics at work is a real shame, because it robs us of the opportunity to see how we can still respect and interact with people who might have different opinions than us. Imagine saying, “Here’s Ryan, a smart guy who believes the opposite of me, but whom I respect. We’re working together, and I need to be understanding about the fact that he has opinions very different from mine.” That would be very healthy. The less we have the opportunity to meet people with different opinions from us, whom we also respect, the more we end up in the isolation of misbeliefs.

Today I talked to a covid denier, who thinks I’m one of the worst people in the world. She’s viewing things through her social media feed, and everybody who doesn’t believe what she does has been erased from her life. I, in contrast, wish we could find common ground.

RH: I’m sitting here thinking that if stress causes people to seek order and a villain, maybe the converse is true: a lack of stress might increase a tolerance for ambiguity. If that’s the case, maybe therapists can play a role in reducing people’s susceptibility to a funnel of misbelief, without having to delve into the details of their misbeliefs.

Ariely: I think all therapy should have a component of increasing resilience, and that means increasing friendships, and it means more loving relationships.

Ryan Howes

Ryan Howes, Ph.D., ABPP is a Pasadena, California-based psychologist, musician, and author of the “Mental Health Journal for Men.” Learn more at ryanhowes.net.

Dan Ariely

Dan Ariely is a researcher, professor of business administration, and founding member of the Center for Advanced Hindsight. His books include Irrationally Yours, Predictably Irrational, The Upside of Irrationality, and The (Honest) Truth About Dishonesty.