“I made it!” I think, panting. “I’ve beaten my client to our session!” My Manhattan psychotherapy office is a stage set—large, well lit, and aesthetically coherent—and I loathe getting caught “backstage.” I hang up my tailored coat, inhale, and decide that I have indeed made it. It’s January 2020.

Two months later, I’m floundering through a teletherapy session with my client Don, in the basement of my Brooklyn home. I’ve had to move locations “mid-scene,” as our main quarters have become dominated by my husband’s board meeting and our two-year-old, raging against his nap. I’m wearing sweatpants, a button-down shirt, and a king’s robe—a Halloween costume I found on the floor and wrapped around my shoulders to keep warm. “I’m so sorry,” I say, cringing in defeated mortification. “It’s really cold down here…” We both laugh. And as we do, a shared sense of aliveness enters the scene. Don continues, seeming more self-reflective and participatory than usual. For years, he’d been reserved and highly curated. As the session ends, he thanks me for being “genuine” at this “challenging time for all of us.”

I shut my laptop, feeling particularly connected to Don, to my work, and to myself. Then I walk upstairs to free my son from the nap that’s not happening, leaving my costume behind.

Seeing clients through the COVID-19 crisis has shown us not only that psychotherapy can be effective outside the traditional frame—complete with an office, couch, and a therapist who never breaks character—but also that shattering the frame when necessary, and allowing our humble humanness to be present, is actually necessary to connect with each unique client.

Well over a year into teletherapy, whenever I’m asked when I’ll “go back” to an office, I wonder what “going back” would mean. Hurrying and running from my clients? Trying (and failing) to hide beneath a costume? Denying them, and myself, my best clinical resource: my true self?

My work with my client Don is a clear example of the contrast between my pre-pandemic approach, and what both my clients and I are capable of now. The work Don and I did over the years was certainly meaningful, but our pre-pandemic scenes were sometimes akin to what legendary director Peter Brook calls the deadly theater: commercial theater produced solely to satisfy the expectations of the masses. We sat in the right chairs and spoke our lines like obedient actors. Don chose his words cautiously, as if he might flub a line, haltingly telling me things like, “I’m getting better with boundaries…” And I’d reply, “I appreciate your efforts…”

One day, pre-pandemic, while Don was mid-sentence, my phone buzzed. It was my son’s daycare—I had to take the call. But I was consumed with guilt for disturbing Don.

“Is everything okay?” he asked, sounding genuinely concerned.

“Yes,” I lied. “Please continue, you were saying—”

I said the right line. But my eyes screamed: I broke character! Pretend this didn’t happen! And those cues aren’t exactly an invitation for someone to open up about themselves.

Part of me knew better: I’m a trained actor who teaches workshops for therapists on how to use oneself authentically to connect with our scene partners. I’m acutely aware of how subtle facial expressions and tones of voice reveal emotional reactions. And yet, with Don I was too self-conscious to be fully present with him—and one of course must be present in order to play, as the great psychotherapist Winnicott recommended we do with every client. Instead, I tried to deliver what I thought Don wanted: a therapist who acted like a therapist. And that meant there was a conspicuous lack of freedom and aliveness between us.

We therapists create deadly therapy, much more than we realize. Upon reflection, I can now see I exacerbated Don’s own fear of getting caught “backstage,” by trying to disavow what I had plainly revealed to him with my face and body language: that the call had made me feel worried and guilty (the daycare had told me my son had a fever, but unfortunately I wasn’t able to pick him up right away). Like screen actors, we reveal volumes of subtext with our eyes to our scene partners and audiences, reflexively and at the speed of light. By attempting to mask my reality for Don in some kind of clinical neutrality, I implicitly sent him the message that he too should simply ignore his present reality whenever it comes into conflict with social and professional expectations.

Then COVID stole the show. And the abrupt dismantling of our set and change of costumes awakened us to ourselves, and to our relationship with one another. Though we were now separated by screens, we were no longer divided by the performative expectations that had kept us at an emotional distance.

As we carried on each week, I was amazed to discover that when my son interrupted our scenes, Don would share more rather than less. He’d light up and tell me about his dreams of having kids, and his own mortifying tales of video meetings gone wrong.

I no longer tried to hide backstage—I couldn’t really anymore, what with my son screaming in protest when he was denied a second episode of Elmo, or a bowl of strawberries, or the entire outside world. I stayed present in the spotlight and, like a committed improv partner, I responded with Yes rather than No.

“I guess you’re not the only one who’s had enough of this quarantine,” I’d say, as I allowed my face to respond with genuine embarrassment, frustration, and contrition, inviting Don to join me in speaking freely.

Don and many other clients have since consistently reflected on their thinking, feelings, and choices with more risk-taking vulnerability, brave self-awareness, and openness to change than I had witnessed before COVID. I can’t imagine any therapist wanting more for their clients. Don, for one, has told me:

“Y’know there were definitely times this past year when I’d get frustrated because you changed our meeting time or didn’t understand my feelings right away. But when I stop and reflect, I appreciate that you need to acknowledge your own boundaries, your own needs, first. From there you can help me to focus on mine. I need to do more of that myself in my life. I’m really grateful for our time. Even when the computer crashes or your son screams, you’re still there, making the effort to hear me, to find me wherever I am.”

So, as I contemplate the future of my practice, my priority is to keep moving forward, not to bounce back. As I sort out what that means, I’m asking myself: Why did it take a pandemic for me and my clients to reach this level of connection and creative freedom? It’s not as though the discoveries Don and I made were unprecedented or revelatory. Even the most theoretically opposed therapists have agreed for decades that an authentic relationship between client and clinician is always the priority in psychotherapy, however and wherever it takes place.

Along these lines, in my “acting” workshops for therapists, I’ve always invoked Peter Brook and reminded my peers that the only thing necessary to create an event— in theater or in therapy— is two people in an empty space. That’s true in an office or between computer screens—as long as both scene partners maintain an authentic exchange of attention—starting from where they are, as opposed to where they think they should be—and stay in the scene no matter what.

And though I’ve practiced the art of therapy with this in mind for years, often to great effect, still one night recently, while putting my son to bed, it occurred to me why an inexplicable something wasn’t entirely authentic about my pre-pandemic “scene work.”

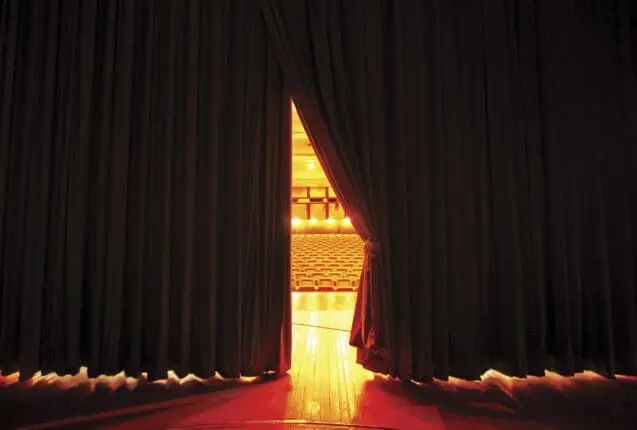

I had just decided to give up my office and I was flooded with grief. That office was more than an empty space. It was my professional identity, a majestic theater I had worked long and hard to create, with a proscenium curtain which I had learned to hide behind.

As I snuggled with my son, and sang the same bedtime songs my husband and I have sung to him since he was born, I realized that every night I worked late, in the stage lights of my office, I wished I was home tucking him in. In fact, I wanted to be able to put him down for his nap every day as well—even if said nap failed to meet my expectations. I wanted to pick him up from daycare as often as possible, and to have dinner with both him and my husband every evening. But I just didn’t think it was possible. “No successful therapist would do that,” I told myself. Much to my surprise, I am doing exactly that right now, while my practice and my clinical work has only expanded.

As I continue to work from home and set up a more permanent (and soundproof) virtual office, the scenework between me and my clients increasingly feels alive and free. Various versions of my clients that would have previously tended to hide “backstage,” are now showing up in the spotlight. Many of my scene partners have become emboldened to tell me, swiftly and directly, when I’ve disappointed them or offended them in some way. Others are quick to let me know when they need me to say more or to say less. And still others test boundaries like never before (e.g., pushing back on same-day cancellation fees etc.) But this only speaks to the safety and freedom we have found through our therapeutic relationships. At the same time, more clients than ever before are able to work through conflicts with me, rather than avoid them. And I’ve received more open, sincere “thank yous” for my commitment to them than I ever imagined receiving in my whole career.

If I ever do work with clients in an office again, I will insist on working with this same level of emotional openness. And if my son’s daycare calls mid-session, I will excuse myself, answer the phone, take a minute to decide my best next move, then let the client know where I’m at, apologize, make it up to them however I can, and from that place of grounded presence, give my scene partner my undivided attention.

As I envision my current aspirations for my work, I recall an interview with actress Lauren Ambrose when she played Juliet for Shakespeare in the Park. She had given birth not long before and she acknowledged the irony of breast-feeding while playing a love-crazed adolescent. But rather than try to mask her maternity to meet anyone’s expectations for her role, she started from her present reality, and found that the love she felt for her son was exactly what she needed to bring Juliet to life. She said, “Having my son… makes me a better actress. Just the feeling and the love that expands in my … being.”

When I saw Ambrose’s exuberant performance, I understood what she meant. She shared her authentic self entirely, while also staying present with her scene partners and her audience within the boundaries of her role. It wasn’t a play about a new mother, it was Romeo and Juliet. And yet she couldn’t have brought that story to vibrant life without allowing herself to be the mother that she was, the complex human, for all to receive, recognize, and identify within ourselves.

One day, when it’s safe, I will get another office. And it’ll be close to home. This way I can tuck my son into bed every night and walk to work–preferably without the fear of getting caught “backstage.” I no longer want to “beat” my clients to session, only to join them there, whatever there may mean for them and for me in any given moment.

Photo © iStock/MarioLisovski

Mark O'Connell

Mark O’Connell, LCSW-R, MFA, is a psychotherapist and author in New York City. He teaches workshops based on his book The Performing Art of Therapy: Acting Insights and Techniques for Clinicians, and writes for Psychology Today and The Huffington Post, as well as clinical journals.