From the moment I met the Correys in my waiting room, I was baffled about why they were together. Frank was tall, good looking and suave; Donna dowdy and sullen. They were both in their mid-forties, although Frank looked younger than that and Donna older. Frank was a wealthy businessman and realtor. Donna was a housewife. Every other week for a year, I saw them, during which time I tried pretty much every trick in my therapeutic arsenal. I spent hours discussing their case with trusted colleagues and read up on their particular problems. And in spite of all my efforts, the Correys were one of my most spectacular failures.

At our first meeting, Donna barely bothered to greet me, and stared resentfully at Frank. As soon as we were seated, Frank jumped in to complain about Donna’s spending. He was clearly used to being in charge, confident and eager to explain their situation. And Donna was used to being passive and angry.

Frank explained that even though they lived in a town with only a grocery store and gas station, a town one hundred miles from the nearest mall, Donna used catalogs and the shopping channel to spend nearly $8,000 a month. I was appalled. Of all the questions and reactions I had to this case, my big question was—how could anyone stay married to such a loser wife?

When her turn finally came, Donna pointed out that Frank was a millionaire and the sums she spent were insignificant. She complained that Frank was almost never home, and when he was home, he stayed in the basement managing his stock portfolio on his computer. She agreed she was depressed.

At the end of that first session, I made a few recommendations to the Correys—that they tear up their credit cards, that Frank come home for dinner a couple nights a week and that they have a date as a couple. Neither one of them was happy with my suggestions. Frank insisted time demands made it impossible to spend more time with Donna. Meanwhile, Donna refused to cut up her credit cards. But they let me bully them into agreeing to try these assignments and we rescheduled for two weeks later.

Somehow, no matter how carefully Frank and I tried to control her, Donna found ways to charge stuff or order junk over the Internet, Although she said antidepressants helped, Donna was still mildly depressed and still not cooking or going out in her community. Frank stayed mad about Donna’s spending, although not that mad. Meanwhile, no matter how therapeutically neutral I tried to be, I remained appalled by her extravagance.

By now our sessions had lost any therapeutic momentum. Increasingly, I felt as if I were dragging a barge across the desert. The couple would fly in, report little change in Donna’s symptoms, Frank’s work habits or their relationship, and fly out. Both said they were dissatisfied with the relationship, but after 22 years of marriage, neither was considering divorce.

The less progress I saw in our sessions, the harder I tried. I utilized every technique I could think of. How could I work with someone who was about as different from me as a woman could be? Donna was passive, preoccupied with consumer goods and she actively disliked exercise. She was bored by trees and prairies and had no interest in education. That boggled my mind. How could anyone not be interested in education? I knew I was being judgmental, but I was convinced that I knew how to be happy and she didn’t. There was no question in my mind that my way of being in the universe was better than hers.

As I worked harder and harder to fix this couple, they seemed to become more locked into their original problem behaviors. One day, I had it with the Correys. When Frank found that Donna had opened a new line of credit and charged another $10,000 of purchases, I fired them.

I thought a lot about the Correys in the months after our termination. I’d ignored the wisdom that people only change when they feel deeply accepted for who they are. Instead, I’d let my own values about spending prejudice me against Donna. And I had other values conflicts as well—over reading, education, gardening and the importance of taking action.

A wise therapist once told me that our first task in any therapeutic encounter is to find something to respect in our clients. Without respect it’s impossible to really help anyone. I realize I flunked Therapy 101. I didn’t respect Donna and I let that important fact slide. I suspect Donna sensed my lack of respect. She had no connection to lose with me. The big lesson from the Correys was that I need to find something I can truly and authentically respect or I need to get out. I can’t pretend respect. And without it, there is nothing on which to build a therapeutic alliance.

Being a therapist is intellectually taxing, emotionally draining work, and respect is what fuels the process; it’s what gives us a reason to care. Without it, the work is mechanical, for us and our clients. With no respect, there can be no connection, and without connection, therapy loses its meaning.

This blog is excerpted from “My Most Spectacular Failure” Read the full article here. >>

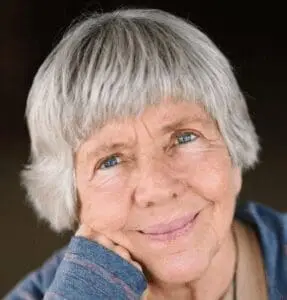

Mary Pipher

Mary Pipher, PhD, is a clinical psychologist, author, and climate activist. She’s a contributing writer for The New York Times and the author of 12 books, including Reviving Ophelia, Women Rowing North, and her latest, A Life in Light. Four of her books have been New York Times bestsellers. She’s received two American Psychological Association Presidential Citation awards, one of which she returned to protest psychologists’ involvement in enhanced interrogations at Guantanamo.