This article first appeared in the January/February 2009 issue.

In the private sanctuary of our offices, most of us can usually keep the emotional barometer within a comfortable range. Because therapy builds slowly on an established relationship, confrontations and criticisms, when they occur, tend to be muted and indirect. When we’re activated by a challenging client, we have at our disposal an ample theoretical framework—transference, countertransference, family-of-origin issues—for keeping attacks at arm’s length and helping us keep our composure.

But when we step outside our offices to apply our therapy skills in doing public work, the rules of engagement are vitally different. A journey through racism, sexism, homophobia, or other thorny and contentious issues means traversing a rockier road.

Facilitating dialogue on these topics often brings together people who’ve been historically divided, with little personal investment or trust in one another. We can’t hide behind the walls of a private office: we’re exposed, “out there,” judged in a court of public opinion that isn’t always kind or forgiving. Furthermore, we have no widely accepted framework or vocabulary to serve as a guide when the going gets rough—which is something I can testify about from painful personal experience.

It was two o’clock on the morning of a summer day in 1988. I’d been lying awake for hours, tossing and turning on the twin bed of a retreat center at a beautiful national park in South Carolina. I’d been facilitating a diversity-training session for mental health professionals whose clients were mostly poor and working-class blacks and Latinos. My job was to help them become more “open, aware, and sensitive” to racial issues, but the first day had been an unmitigated disaster. Now, every time I closed my eyes, I saw and heard the evidence of my failure—participants’ comments and faces flashing through my mind, one after another. I was being haunted by sneers, snarls, looks of disparagement, disdain, and disgust.

That morning, I’d begun presenting a list of “Ten Strategies for Coming to Terms with Race in Clinical Practice.” At first, the group seemed respectful, though slightly distracted. By the time I’d gotten to my third point—that “whiteness is privileged, and being a person of color is a disadvantage”—I could sense a thickening of the air.

At the back of the room, two gray-haired gentlemen, both wearing wired-rimmed glasses, were whispering to each other; one shook his head emphatically in agreement, with a grim smile. Trying to break the tension, I somewhat playfully asked, “So what do you guys think about all of this, back there in your corner?” Both looked slightly embarrassed and hesitant about speaking, but after some prodding, one of them said sarcastically, “I don’t think you really want to know what I think!” “Believe me, I honestly do: go for it,” I encouraged, trying to defuse some of the tension.

“Well,” he said, “I think this is all bullshit, and I have no intention of sitting through two and a half days of listening to you whine about how whites have done this to you and whites have done that to you. Maybe it’s time for you and the rest of your soul brothers and sisters to start taking responsibility for your problems and stop using us whites as your whipping boys. I know exactly where all this is going, and I have better things to do with my time!” There were nods of assent, sarcastic laughs, a few high-fives.

I was completely unprepared for this reaction, first shocked, then hurt, then angry. I retorted in a louder, more aggressive voice than I’d intended, “Where do you think it’s going? Where is it going?” Without waiting for an answer, I continued, “Maybe we both know where this is going! You want to talk about responsibility? Why don’t you whites ever take responsibility for what you do?”

The room was no longer silent, but buzzing with muttered exchanges, along with boos and jeers. One participant, sitting less than five feet away from me, turned to her colleague and said loudly enough for me and others to hear, “And this angry bigot thinks he’s going to teach me something! I don’t think so! I refuse to sit here and allow him to try to make me feel guilty for everything that I’ve worked hard to get. Hell no!”

That night, as I lay there sleepless, I saw not only the hostile, white faces of this group, but also the faces of my own family: I saw my mother, a native daughter of South Carolina, and I felt the pain she’d suffered growing up as a black woman in the segregated South. I saw my father and my grandparents, who wore the emotional scars of racism their whole lives. I thought about how much suffering my ancestors had undergone, how much violence and hatred they’d been exposed to, decade after decade. I remembered looking at the majestic, old trees in this park, and all I could think of was the line from Billie Holiday’s haunting lyric about the lynching of blacks, “Southern trees bear strange fruit.” I couldn’t remember another time in my life when I’d felt so misunderstood, beaten, and hopeless.

Changing the World

As a child, I’d listened with horror to the countless stories that my parents and grandparents had shared about their years in the segregated South. I saw firsthand the divide created by racism. It was so hard for me to grasp how and why skin color could matter so much. I was constantly reminded of how much my forebears had given to make life better for my generation, and how great was the obligation for us to do the same for our posterity. I grew up with an urge to do my part to change the world.

I’d attended three large, predominantly white, universities and had never had a classmate or professor of color. While I did everything I could to fit in—to be one of the crowd, to avoid appearing like I had a chip on my shoulder—on the inside, I was dying of loneliness and a chronic sense of otherness. No matter where I was—the classroom, the dormitory, or just chillin’ on campus—I was painfully and acutely aware that I was other.

In classes, when a professor or a fellow student made uninformed or grossly negative assertions about black people, I could speak up amid stares and glares and be accused of being defensive, angry, or hypersensitive, or I could say nothing, knowing that my silence would be taken for agreement. These experiences, painful as they were, provided a kind of unintended internship for the work that I’d ultimately do.

When I got my doctorate in family therapy, I went to work in community-based organizations in New York and Pennsylvania, believing that I’d change the world, one black, inner-city neighborhood at a time. To my disappointment, the black youths I tried to help didn’t seem willing or able to understand the complexities of racism and how it affected their lives: they seemed strangely complacent, without urgency. At the same time, the whites I worked with didn’t seem anxious to change the status quo either. I found the lack of fervor by blacks and whites, and certainly my own lack of impact, deeply discouraging.

So I tried another tack. I began using the experiences from my community-based work to formulate ideas about what therapists needed to know to work with disaffected populations. I began conducting workshops for therapists focused on increasing their clinical effectiveness with African Americans and other clients of color. Much to my surprise, these workshops were a hit. People got it! And, within a few months, I’d begun to receive a steady stream of requests from diverse organizations. It was work I loved, not least because I finally felt that I was making a genuine difference.

After several years of doing workshops, mainly to help white clinicians do therapy with black clients, I wanted to shift my focus to the bigger issue of racism and its effects on white people, as well as blacks: I wanted to move the conversation from “understanding African American clients” to grappling with the wider impact of racism in society. The workshops I offered with that concept in mind weren’t so much about a clinical approach as they were personal and experiential explorations of what racism meant for people in their own lives and the way they’d learned to understand the world.

The largely self-selected participants of these workshops—mostly white liberals—wrote me countless letters afterward, telling me they’d been transformed, their lives forever changed! My ego swelled. I remember thinking “I’m pretty good at this: this is my calling!” I began to work with larger organizations with less dependably “progressive” participants, no longer preaching just to the converted, but to the heathen—many or most of whom were definitely not diversity enthusiasts.

Then I received the fateful offer I couldn’t refuse: to facilitate a diversity training session in my mother’s home state of South Carolina. So at the end of that awful first day, part of the reason for my distress—besides the hurt of being attacked and my wounded pride at seeing my self-image as Racial Healer crumble—was that this wasn’t just another training: it was taking place in a region fraught with history for my family, my people, my country.

It had all come to ashes. The second day was a painful and humiliating extension of the first. About a third of the group didn’t return—without reason, excuse, apology, or notification. Those who did return clearly did so out of obligation and without conviction. Physically fatigued and emotionally devastated, I pushed forward, robotlike, spewing meaningless words, designed primarily to get me to the next break. The final day, the few remaining participants and I limped through the rest of the training. It was nothing more than a cursory gesture for all of us; we stayed because we felt we had to.

The two-hour flight back to New York seemed like an eternity. “I can’t do this anymore!” I thought, “It isn’t worth the costs to my soul, spirit, or sense of self.” I’d put my training and passion to some other use: I’d work with people who’d value me and appreciate what I could offer.

Resolved to walk away from it all, I felt a sense of relief and peace. Back home, ready for the first time in days to get a decent night’s sleep, I fell into bed, closed my eyes, thinking that it was finally time to stop hitting my head against a wall. I’d never felt so tired.

As my eyes were closing, I was interrupted by my great-grandmother, Anna, whose image hovered above my bed. She’d lived with my family until she died, when I was junior in college. Now, leaning over me, lovingly but with an obvious look of disappointment, she administered a reprimand: “Tired? You say you’re tired? Who are you to be tired? People have been hosed, jailed, beaten, shot, and lynched for you and never once complained about being tired. You don’t even know what tired is! You want to quit because it’s too hard, but you can’t be loved by everybody. It isn’t about you, and you have to stop making it about you. I don’t want to hear nothing else about you quitting or being tired!” Then her image evaporated. I continued to stare at the ceiling, thinking about her words, until it became easier for me to breathe and I could finally sleep.

I can’t say that this was exactly my conversion on the road to Damascus, but I was disturbed enough the next morning that I decided that I couldn’t quit just yet; maybe I did need to hang in and not give up so easily, maybe even grow up a little.

Chasing Ambulances

As I went about doing other workshops on diversity, the shadow of South Carolina loomed large. I felt less apt to rattle off quick, assured, ill-thought-out responses. I became less spontaneous and “authentic” in some ways, and more cautious. It was like learning to drive a standard shift again, all jerky and prone to unexpected lurches and stalls. But something new began to dawn on me: the power of patience, of being more willing to back up and try again, to listen before rushing on. It wasn’t as much fun as being a self-assured star, but slowly I began to “find my touch.”

A few months later, I was sitting in on another therapist’s workshop, devoted to “Effective Therapy with African American Families.” Watching from the audience, out of the spotlight, I could see shades of myself in the presenter, both in her obvious commitment and in her blind spots. The information she imparted to the predominantly white audience was cogent and precise, but provocative, and I could see how difficult it was for many in the audience to digest the information. It was clear that they felt they were being personally attacked—and the more attacked they felt, the more defensive and hostile they became. I could feel from their perspective what she was doing wrong and why it wasn’t working: she was self-righteous when she should have been curious, hectoring when she should have been receptive, counterattacking when she should have been empathizing with her attacker’s confusion and anger. “Damn,” I thought. “That’s just what I was doing in South Carolina.”

During several ensuing trainings, I made a concerted effort to avoid getting seduced into “chasing ambulances,” as I began to refer to the process of being mesmerized into going after participants’ provocative, highly charged comments. While that worked as long as the exchanges occurred among the participants, I wasn’t so great when comments were directed at me. With flashbacks of South Carolina, I often clammed up, my head nearly bursting with pent-up feelings, or I jumped too quickly into the fray, getting involved in nonproductive, one-on-one sparring matches. In either case, my inability to manage this recurring dynamic was stifling my effectiveness. I recognized that whatever strides I’d made since the South Carolina nadir, I definitely had room to improve.

One cold wintry Sunday afternoon after a long, intense workweek, I was sitting in my living room watching a tight NBA basketball game between my beloved Lakers and their archrivals, the Sacramento Kings. During the last, breathless seconds of the game, the Laker star player was about to score a basket for a sure win. But instead of just keeping it simple, he elected to do a flashy 360-degree slam-dunk, missed the shot, and lost the game. The Laker arena fell silent. The television commentator’s remarks were merciless: “This is what happens when you allow the show to get in the way of the game.”

His words struck me like a gong. It was as if he were talking to me, not as a basketball fan, but as a trainer/consultant. That’s what I’d done—let the show get in the way of the game, letting my desire to be a heroic warrior for social justice get in the way of the slower process of working with people where they were to build relationships and expand awareness.

A few days later, I traveled to Illinois to facilitate a diversity-training session for 25 program directors and supervisors of a large county department of community mental health. At midmorning of the first day, a deeply religious Latina had just shared a story about her struggles with what she thought was the inherent sexism of her church, which routinely denied advancement to women while it promoted less dedicated men. I acknowledged this apparent unfairness and suggested that this was what institutional bias looked like—and that in our work, we need to be sensitive to these issues.

At this point, Vinnie, who’d been quiet but highly expressive—sighing deeply, rolling his eyes, and sucking air between his teeth—decided he’d had enough. “Maybe it’s Scripture that says women shouldn’t be church leaders, not sexism!” he barked. I replied, “That’s an interesting view, which in all honesty I’d never considered.” I asked Sonja, the Latina, what she thought of that view. “I think it’s a bunch of bull,” she said. “Yeah, maybe Scripture is wrong or at the very least, misinterpreted,” I said.

Now Vinnie was really mad. “Doctor, Scripture is never wrong!” he practically yelled. “You know I’ve been sitting here for hours now, and I don’t know why. I’m getting nothing, not a goddamn thing, out of this training! What is your endgame? Do you even have one? Speaking of bull, you know what bull is, Sonja? This training is bullshit!!”

As is often the case with outbursts like this, the room went quiet, and the participants anxiously waited to see what would happen next. Vinnie was sitting upright, red-faced and breathing heavily. To my surprise, instead of feeling under assault, I felt that this could be a moment of redemption, an opportunity not to “allow the show to get in the way of the game.”

I could see that Vinnie felt deeply threatened, and that his anger was a mask for anxiety. Instead of lashing out, I thanked him for his courage and honesty. I went on to assure him that I understood that my comment about Scripture’s being wrong was hurtful to him and left him feeling angry toward me. “I’m sorry that, so far, I’ve failed to make this training meaningful for you. Please know that I’m going to work really hard so you get something worthwhile from it. I trust that you’ll let me know if I succeed or fail.”

A sigh of relief radiated around the room. Everyone sensed the shift. The message was that Vinnie and I could stay in relationship despite our disagreements. At the end of the training, we even exchanged a heartfelt hug. I’m not sure that I’d offered any nuggets that stayed with him, but I knew that our moment of hanging in together through our conflict had registered with him in a way that any lecture about “tolerance” or “mutual respect” wouldn’t have.

Connecting with “the Other”

Since then, I’ve seen my role in a different way. My work isn’t about educating the unenlightened: it’s about helping people see the insidious impact of the “otherness process”—turning a person or a group into “the other.” This may be a universal human experience: the manufacturing of “the other” promotes rigid polarization, based on the idea that one group is right and the other is wrong. Once this positioning has occurred, constructive engagement is virtually impossible.

The creation of “the other” is the dynamic at the heart of divorce and personal antagonisms, and it has always been central to racism, sexism, homophobia, and ethnic persecution. The mindset is always the same: “I/we are right, you/they are wrong, and if anything is to change, you/they must change.”

My original identity as a self-righteous crusader for social justice had tripped me up. To become a true agent of change, I couldn’t afford to see the world—literally and figuratively—as either black or white, us and them. I had to recognize how easily I myself could become “the other.” I began to let in something that white women and gay white men had repeatedly reminded me of: that they weren’t just white and privileged—they were also female and gay. To them, I was, as a heterosexual male, “the other,” interacting with them from my own position of privilege. I needed to come to the uncomfortable realization that there may be a tiny piece of an oppressor in many victims—and a tiny bit of a victim in many oppressors.

When I’m severely tested in my work of helping individuals and groups bridge their differences, I’ve learned that the “otherness process” is usually at the root of the problem. Whether it’s a white client in therapy who disparages “niggers” as he discusses his daughter’s attraction to black males, or a member of the clergy accusing me of the being the Antichrist, who’ll burn in hell unless I change my tolerance of homosexuals, my position is the same. I make every effort to adhere to the three core principles that guide my work: (1) the attack, insult, or accusation may be about me, but my reaction and how I respond must not be about me; (2) to find the healing and transformative potential in dialogue, my job is to respond in ways that promote, rather than suppress, heartfelt conversation; (3) validation is the bridge to constructive engagement across differences.

Anyone who wishes to move outside the consulting room to address racial, ethnic, or sexual differences must rely on the bedrock belief that everyone has redeemable parts, and you can find them if you have the will and the patience to look. The biggest lesson from my South Carolina meltdown was recognizing my assumption that there was nothing in any of the participants that could be redeemed: they were all 100-percent “other”—belligerent, resistant, recalcitrant, closed-minded bigots. That they’d shown up for the training, were engaging in the process, were expressing their views in ways that were (God knows) honest and transparent, and had long since committed themselves to the helping professions hadn’t registered with me.

To do this kind of work, we must learn to see through the myth of otherness: we must recognize that all people, no matter how flawed, have redeemable capacities in their being. It’s our responsibility to find their virtues and connect with them. Admittedly, when facing hostility and rejection, our task poses formidable challenges, but failing to look for the redeemable qualities in “the other” amounts to a retreat from the possibility of relationship.

Once we move outside our offices, idealism and good intentions aren’t enough. We must bear in mind a fundamental principle of our work: whatever the seductions of the “otherness process,” our apparent enemies have the potential to be fair, just, kind, and true—in other words, genuine human beings, just like us.

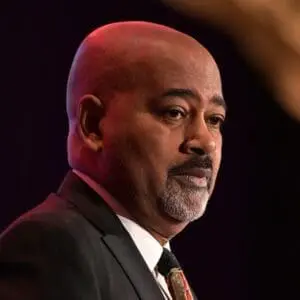

Kenneth V. Hardy

Kenneth V. Hardy, PhD, is President of the Eikenberg Academy for Social Justice and Clinical and Organizational Consultant for the Eikenberg Institute for Relationships in NYC, as well as a former Professor of Family Therapy at both Syracuse University, NY, and Drexel University, PA. He’s also the author of Racial Trauma: Clinical Strategies and Techniques for Healing Invisible Wounds, and The Enduring, Invisible, and Ubiquitous Centrality of Whiteness, and editor of On Becoming a Racially Sensitive Therapist: Race and Clinical Practice.