I’d been a therapist for 25 years when Greg and his wife, Lisa, came in for treatment. In my experience, husbands whose wives drag them into therapy for sex addiction are usually resentful and closed off. But Greg seemed relaxed and open right from the start. Lisa, frowning, sat stiffly with her arms crossed over her chest.

At 45, Greg had already retired from his tech job and was now flipping houses to bring in some extra cash. Lisa, an executive assistant at a national nonprofit, had been shocked and disgusted when she’d stumbled on a link to Greg’s browser history on their computer and found it was full of porn. She was a devout Catholic and deeply involved in her church; Greg had lost interest in religion many years before.

With his porn-watching habit now out in the open, Greg had confessed to a recent interest in exploring new kinds of sexual activity, like swinging with other couples, gay sex, and bisexual forays. But Lisa’s visceral revulsion had made him question whether this was “normal,” and he’d readily agreed to therapy. He said he was open to the idea that he was a sex addict, but he wasn’t really sure the label fit him. All he wanted, he said, was to see where his newfound sexual curiosity might lead him and, while he’d never force Lisa to do anything she didn’t want to, he’d like it if she joined him.

Lisa couldn’t identify with any of this. Just thinking about the kinds of things her husband was finding on the internet horrified her. She valued monogamy and relational sex, and for her, Greg’s going down this virtual rabbit hole was just as bad as cheating on her with other women. She was hoping that therapy with me would “fix” him and, subsequently, their fractured marriage.

This was at a time in my career when I still believed in the sex addiction model. So as I did with all my clients, I urged Greg toward sexual abstinence, from himself and his wife, in the belief that it would eventually lead him back to “normal” sex, which meant monogamous and relational. What neither of them knew back then was that my own rather fundamentalist adherence to this model was connected to the fact that I’d long considered myself a sex addict.

Even though I’d been out as a gay man for decades, I still felt disgust at my erotic interests and fantasies, which didn’t match how I wanted to see myself. Although several therapists over the years had told me I wasn’t a sex addict, I fired all of them until I found one who agreed with my self-diagnosis.

In the world of sex addiction treatment, a key tenet is that while porn use may begin with only a certain type of porn, it inevitably escalates to a desire to view more and different types. Like me, it seemed Greg had stepped right out of the sex addiction playbook. Every time he tried to stop his porn use, it only increased his sexual curiosity. And each time, both Lisa and I lamented it as a treatment failure: “backsliding” in the addiction vernacular. Greg, in contrast, started wondering aloud if he was evolving rather than backsliding, given how much he enjoyed the new things he was seeing and feeling.

Viewing his porn habits through the addiction lens, I tried to help him see how dangerous it was to him and his marriage, as Lisa grew increasing disgusted and fed up. But as Jack Morin, author of The Erotic Mind writes, “If you go to war with your sexuality, you will lose and create more problems than you started with.” At that point in my own personal and professional evolution, I still didn’t understand what that meant. When clients whom I’d labeled sex addicted would go in and out of sexual binges, I saw it as fitting the loss-of-control aspect of addiction, not what happens when you’re fighting your sexual and erotic orientation.

Greg and Lisa had come to me with an erotic conflict, which was fundamentally a couple’s conflict. But as a sex addiction therapist, I’d made him the problem and her the victim. My approach, I now realize, should’ve been to help them have erotic empathy toward one another, but that didn’t happen. Instead, they drifted further apart.

As their therapist, I felt helpless, especially since I’d started growing uneasy about the sex addiction perspective, which had been the foundation of my work for so many years. And secretly, I grew more and more admiring of Greg’s openness and honesty about his desires. Here was a man my age who was allowing himself to become more comfortable with his sexual evolution. He was always interested to hear what I had to say, but didn’t accept it at face value. When I took his wife’s side, emphasizing relational sex, he’d ask, “Why can’t I get off on both relational and objectifying sex?” But he wasn’t angry or defensive when he said this, just posing a straightforward question. This allowed me to watch and listen to him differently than any other client I’d ever had.

Eventually, Lisa concluded that we weren’t going to be able to “fix” Greg, and she wouldn’t be able to stay with him. There was no more anger on her part, no more accusations, just a mature acceptance of unresolvable conflict. Although saddened, Greg agreed it was best for both of them that they divorce. Nevertheless, he continued to see me in therapy for several more years.

During that time, he’d often tell me about his sexual and erotic explorations. He began having sex with women and engaging in fantasies he’d seen in porn. This led to him having sex with couples and then with men alone. He told me he was seeking sex daily and sometimes would meet people more than once a day. Because I was still hanging on to the addiction model I’d been trained in, I saw this as evidence that he was getting sicker and sicker. I labeled his excitement about his new experiences as “junkie pride.”

Behind my therapist mask, however, I was fascinated by Greg’s explorations. I’d always enjoyed the monogamous sex I’d been having with my husband, but I realized I also had unfulfilled fantasies and desires I’d always shrouded in shame. Even as I issued stern warnings to Greg about the dangers of continuing to engage in behaviors that could have all kinds of negative consequences, I often found myself thinking that watching Greg navigate this new world was like watching a toddler learn to walk. At first he’d stumble and fall—and learn not to do certain things—until finally he found his sexual balance.

Meanwhile, Greg’s enthusiasm for his new discoveries began affecting me in unexpected ways. I started pathologizing his sex life less, while getting more interested in my own. Facing the fact that I’d set aside my own erotic interests to be with my husband, who wasn’t interested in exploring them, I began to admit to myself that I was seeking a way to bring more pleasure into my life. But that meant taking a page out of Greg’s book and no longer denying my erotic self by seeing it as the enemy.

Indeed, I started to like Greg’s treatment plan for himself better than mine. He was opening doors for both of us. A part of me couldn’t believe I had the gall to keep charging him while, in reality, he was teaching me. Instead of seeing his expanding sexual interests as the progression of a disease, I wondered if he’d been right all along, and it was simply the evolution of his erotic life. I also wondered if maybe I wasn’t the sex addict I’d always believed I was.

When Greg eventually left therapy, I realized that he’d outgrown me and my limited understanding of sexual health. I took it as a sign that I needed to evolve in my approach to practice—and in my personal life. I realized that it was time to have some deep conversations with my spouse about the differences in our erotic interests. I was dreading having to bring it up, but my partner surprised me with his acceptance. He’d always known this about me, and he’d never been the one asking me to suppress my erotic self—I’d been doing that to myself.

Years later, I started to run into Greg in gay circles. By then, he was completely out as bisexual. One time, as we were talking, he joked about coming back to see me for therapy. “Maybe I’m still a sex addict,” he winked.

“I wonder whether all that talk about sex addiction is what you really needed,” I responded, silently thanking him for the gift he gave me.

With a big grin on his face he said, “Now I want my money back!”

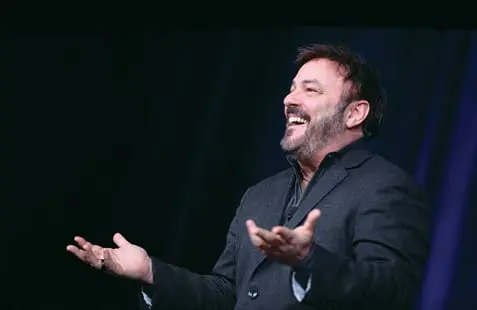

PHOTO BY SAM LEVITAN

Joe Kort

Joe Kort, PhD, LMSW, is a board-certified sexologist and the founder of The Center for Relationship and Sexual Health, and runs a private practice in Royal Oak, Michigan. Dr. Kort, a therapist, coach and author, has been practicing psychotherapy for more than 38 years and has spoken internationally on the subject of gay counseling. He specializes in sex therapy, LGBTQ affirmative psychotherapy, sexually compulsive behaviors, and IMAGO relationship therapy designed for couples to enhance their relationship through improved communication. Dr. Kort is a blogger for the Huffington Post and Psychology Today on issues of sexuality. He has been a guest on the various television programs on mixed orientation marriages and “sexual addiction”. Dr. Kort is the author of several books, including, LGBTQ Clients in Therapy, 10 Smart Things Gay Men Can Do to Improve Their Lives, 10 Smart Things Gay Men Can Do to Find Real Love, and Is My Husband Gay, Straight or Bisexual.