Enjoy the audio preview version of this article—perfect for listening on the go.

I remember the first time I felt unsafe. I was six or seven, and my siblings and I were playing in our front yard under the huge evergreen tree, whose branches fanned out at the bottom to create a cozy cave, perfect for playing whatever game we could dream up. We called it the Secret Treehouse, and it was my favorite place to be.

On that particular day, I remember my mother’s yell cutting sharply through the yard as a strange man we hadn’t noticed before ran away from us and into the street. He jumped into a tan car, where a woman waited for him in the passenger seat. Later, when my parents sat us down and explained what kidnapping means, I understood, and I could no longer play in the Secret Treehouse without fear. Before that day, my world was one way, and after, it had changed forever.

The day I found a lump in my breast felt a lot like that day beneath the tree. It had been a typical day—wake up, take three-year-old son to daycare, drive to work, drive home from work, pick up son, do a million things, put overtired son to bed. I was relieved when I finally sank into the deep, soft cushions of our couch, wrapped myself in my favorite blanket, and snuggled up next to my husband to watch our current guilty pleasure, a crime-family drama on TNT.

Halfway through the episode, one of the main characters, the matriarch of the family played by Ellen Barkin, appeared in a large medical chair, one arm out to the side and an IV pole next to her. She was getting chemotherapy. I was only 37 at the time and had no family history of breast cancer. Self-exams were not a regular part of my routine. Still, I casually reached under my shirt to palpate my right breast. The shock of what I felt there jolted me into an internal dialogue that went something like this: Is that a lump? No, don’t be a hypochondriac. You’re too young for a lump. That’s definitely a lump! But is it hard? Does it move? I have no idea! It’s probably fine. Just keep watching the show. I put my hand down and tried to watch the show, but within seconds I was feeling the lump again.

Eventually, my husband turned toward me quizzically. “I feel a lump, but it’s probably nothing,” I said quickly. Except it wasn’t nothing. This wasn’t a near miss like in the yard that day. This time the bad guy got me, and it was cancer.

The next seven months of my life were surreal. I remember small details vividly: the exact look on my doctor’s face when she felt the lump and recommended a mammogram, the feel of the needle gun pushing through my skin as they took a biopsy, the tinny sound of the words over the phone when the doctor said, “It’s cancer.” Then there was the surgery, the port placement, and the chemo, which of course came with side effects: the inability to see clearly, the inability to sit still, the inability to walk, the inability to function. After that came the hospitalization, the radiation, and finally—ring the bell, clang the gong—I was done.

I’d gone through all of that, but I wasn’t truly present for any of it. Where did I go? What had happened? Initially, putting on my psychologist hat, I thought about depersonalization or derealization, but that didn’t quite fit. Rather than feeling detached, I’d felt trapped in my body, as if locked in a dark closet and strapped to a bed, screaming in panic with no one around to hear or save me. I had no other option than to will myself back to the hospital, week after week, and sit in that oversized, tan, plastic recliner while the poison flowed through my veins. Had I been fully present, I don’t know if I’d have been able to do it. It was like being beaten within an inch of my life and then having to walk back into the building where it happened, over and over, knowing with certainty that I was going to get beaten up again, and not knowing whether or not I’d survive.

I did this for three months. My husband essentially became a single parent, taking on full responsibility for my son while my parents took care of me. At three years old, my son knew I was sick. We bought him age-appropriate books about moms having cancer, and he saw me lose my hair. Once, I fainted in front of him, and he still talks about the ambulance and fire truck that came to the house that day. He’d give me gentle hugs because I was either sore from surgery or my skin was burned and peeling from radiation. He was aware and sweet, and yet his life went on without me. He was shuttled back and forth from daycare, soccer practice, and playdates—and then ushered quietly past me as I slept.

After each hospital visit, I’d set up on the living room couch because I was a fall risk and couldn’t go up the stairs without help. With my massive purple water bottle in hand (you need to hit certain marks for liquids each day), I’d try to sleep, but once the steroids revved up, it was almost impossible to see or lie still. So I’d fidget, stand up and sit down, pace the room, and then cry, because I was beyond tired and just wanted to close my eyes.

Then, abruptly, and with little fanfare, treatment ended. It was December 23rd. We left the next day to go to Boston for the holiday, and after New Year’s I was back to work full-time.

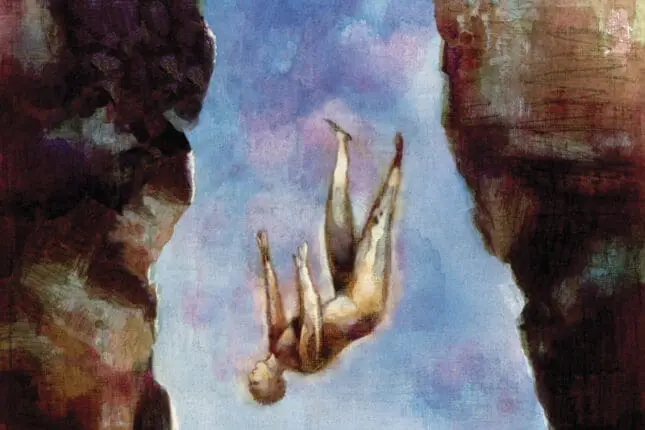

Given my specific type of tumor that feeds on hormones, I was prescribed a course of hormone blockers to take for the next five to 10 years and sent on my way. There was no “Congratulations, you’re now cancer- free!” No balloons fell from the ceiling. No one even told me what to expect in the coming months, emotionally or physically. There was certainly no assurance that I’d never have to go through it again. I once read on a post-cancer blog that ending treatment feels like getting dropped off the side of a cliff, because you go from having near-constant medical support to none at all. I can’t think of a better description—it feels like a free fall.

Returning to life after treatment was hard. Of course, I’d never encourage my clients to take the “Buck Up, Buttercup” approach to life. But in the days following treatment, that’s what I kept encouraging myself to do. I wanted nothing more than to get back to my old life, so I went right back to work, picked up my parenting responsibilities, and tried to focus on everyone’s problems but my own. I didn’t want to think about cancer, and I didn’t want to talk about it.

In fact, for about three months I successfully hid from it, until I was suddenly catapulted back into the hospital: this time, to have my ovaries removed as an additional hormone blocker to help prevent recurrence. It had taken my husband and me three years of heartbreaking fertility treatment to conceive our son. Now, I was being robbed of the opportunity to conceive again and forced into menopause at 38, which would permanently impact my sex life since the hormone replacements given to most menopausal women are off the table for me. Bucking up was no longer an option: I felt too far gone for that.

After the surgery, I struggled to get back to stable ground. By then, the pandemic was in full swing, and everything seemed upside down. I started noticing changes in myself. I was on edge all the time. I avoided mirrors. I hated my bald head, my mutilated breast, and my array of scars. I stopped sitting in the living room, where I’d spent three straight months during chemo. I avoided the kitchen, because a smell could catch me off guard and send me into a panic. I avoided intimacy, because even the thought of sex would create a feeling of emptiness in my body that threatened to obliterate me, like a black hole.

The symptoms seem obvious now: excessive arousal, avoidance, hypervigilance. But at the time, I couldn’t understand what was happening to me, until one day in October of 2020, when I’d just reached the one-year anniversary of my chemo treatment.

There was a chill in the air, and as my son hopped in the car after daycare, he asked if we could put up Halloween decorations at home. I didn’t hesitate to say yes. As we drove through town, I started feeling ill, but brushed it off as my son chatted happily about the finer points of building a “super tall” tower out of Magna-Tiles. By the time we’d arrived home, I thought maybe I had a mild case of COVID. Still, I pushed on, taking down boxes from the attic full of witches and skeletons and bats suspended in midflight.

Then, I came across a small white ghost. It was something my mother had given my son when I was going through the final stages of treatment the year before. He’d loved that ghost; he must’ve listened to the catchy song it played a million times. I was thinking about how this must’ve been a great distraction for him during such a tough time when he grabbed it from my hands and ran off. I could hear the pitter-patter of his feet in the kitchen, and then, suddenly, the ghost’s chipper tune rang out through the air. It stopped me in my tracks, and I doubled over onto the floor. My head felt full of cotton balls, my vision went blurry, my body was wracked with nausea. It was as if I’d been catapulted back into my “chemo body.” I was terrified. I couldn’t understand how it had come back, and how I could be trapped inside it again.

At some point, I became aware that my son was watching me anxiously. I managed to crawl up the stairs on my hands and knees to tell my husband to take him outside. I didn’t want him seeing me like this, not after all we’d been through the year before. Later, after my symptoms had subsided, I frantically googled “can chemo symptoms come back?” That’s when I discovered what had happened. It’s called a chemo flashback, and it was the final piece of the puzzle to help me understand what was going on. I had PTSD.

I’m now almost three years post diagnosis. My hair has grown back, the light brown curls finally brushing the tops of my shoulders. My scars are less visible, at least to other people. And I just graduated from seeing my oncologist every three months to every six months. Life, more or less, is back to normal.

Except it’s not. It turns out there’s no going back to normal after cancer. People tell me I’m a survivor, that I’m brave to have fought and won the battle against cancer, but none of that feels true to me. There’s nothing that feels brave about crying my way to chemo and, on at least one occasion, begging my parents to let me stop treatment because I couldn’t take the side effects anymore. I no more “won” the battle with cancer than someone who dies from cancer “lost” it.

I’m supposed to have a greater appreciation for life now, but I live in a perpetual state of fear that the cancer will come back. The invincibility of my youth is gone. I don’t want to die. I don’t want to leave my husband without a partner or my son without a mother—but I know it can happen. I don’t know that it will, just that it can, and that keeps me up at night.

Still, I haven’t given up hope that there may come a day when the word cancer isn’t constantly playing in the corners of my mind. As I stumble through the process of finding meaning in my experience and living my life in spite of cancer, I see glimmers of hope in small moments, like sitting on the front porch with my neighbor and laughing at the latest meme by @thecancerpatient—“Can I count my tumors as dependents on my taxes?”—while helping her adjust her drainage tubes. It’s probably only funny if you’ve had cancer, which, unfortunately, she has. We met one day when I noticed her “house hat,” as I used to call the ugly but comfortable cotton wrap I wore that signaled to the world I was bald and going through treatment. “Hey,” I’d said. “I used to wear a hat like that.” It’s incredible how cancer can create such a powerful bond so quickly.

I’ve also found glimmers of hope in talking a colleague through what to expect during her upcoming biopsy, and in crying tears of joy with her when she got the news that her tumor wasn’t cancerous. I never thought, however, that I’d be able to hold my cancer experience with just the right balance of vulnerability and restraint to allow it to be part of my clinical practice. Then, earlier this year, Sarah, a 23-year-old woman I’d been seeing for OCD, caught me off guard. We’d been working together for almost a year, and I knew a lot about her, from the name of her dog (Sophie) to the little shoulder shimmy she did when she was proud of her exposure efforts. So when she popped up on Zoom one day with a distraught look on her face, I knew immediately that something serious was going on.

Between body-shaking sobs, she explained that she’d gone to the doctor because she hadn’t been feeling well and that the doctor had recommended getting scans on some concerning lymph nodes. As I listened, the blood drained from my head as a gaping pit opened up in my stomach. I found myself gripping the side of my desk, and I noticed an instinct within me to leave the session—and run. I was viscerally triggered and traveled back in time to the day my doctor had told me to get a mammogram. It felt like there was no way I could make it through this conversation without breaking down and making it about myself. But then Sarah’s voice cut through the fog as she said, “Anna, I’m scared.”

Suddenly, my brain seemed to downshift into a lower gear. The fog cleared, my heart rate slowed, and I was back in the moment. This wasn’t about me; it was about Sarah, and right now she needed me to hold this space for her. So I stayed. I breathed. I checked myself on every word I said before I said it. I used all the present-mind focus I could muster. I found, in fact, that I could hold my own experience within myself and access just the right amount of it to help Sarah hold hers. And, before I knew it, we were saying goodbye, boundaries intact.

It was only then that I let myself break down. I cried for Sarah, for all I’d been through, and for what I knew she may have to endure in the coming months. I knew that if she ended up having cancer and we continued to work together, I’d need a lot of support to support her. I wondered if ethically it’d be better to refer her to someone who wasn’t so close to her experience. But after a lot of consultation with my mentors, colleagues, and therapist, I concluded that continuing our work together would be better for Sarah than ending it.

As our sessions expanded beyond OCD and into the world of scans, biopsies, and, finally, cancer, I was surprised that it wasn’t as hard as I’d expected to hold the balance I needed. When I told Sarah that I’d recently gone through cancer treatment, she became tearful for a moment, thanked me for telling her, and said, “I’m glad I’m not alone in this.” After that, I kept my boundary guard up, always unsure if today would be the day I got it wrong, but more often than not, when I could use my own experience to join with her, I knew I’d made the right decision.

For instance, when Sarah’s body shook with grief as she cried about the likelihood of losing her long, blonde hair, I didn’t hesitate to walk her through my own journey: the extra hair I noticed on the hairbrush one day, the day I decided to shave it all off, my decision to stop wearing wigs and scarves in favor of rocking my bald head, and the process of watching (sometimes with a magnifying glass!) as my hair grew back. Never before had I crossed the boundary of sharing personal pictures with my clients—but this time I did. I showed her a picture from the day I shaved my head; I was wearing huge Audrey Hepburn-esque sunglasses and staring blankly at the camera.

Sarah smiled and said, “You know what? You look like a total badass.”

I smiled back and said, “You know what? You will too.”

As I told her about my failed attempts at tying scarves and the surprisingly awesome ways I found to style short hair, Sarah seemed calmer. Hearing about my experience provided a gentle distraction from the intensity of her emotions, allowing her to engage her rational brain enough to start exploring her thoughts and fears about losing her hair.

Since then, we’ve experienced countless connective moments like that, one of which is laughing together about all the well-meaning but unhelpful things people have said to us about having cancer. (Everything happens for a reason. Really?!) I was also able to help prepare Sarah for her first chemo treatment. (Ask for a chair that doesn’t face directly across from another person. And when the nurses offer warm blankets, take them!)

– – – –

Whether or not we choose to share our personal journeys with our clients, I believe they can sense when we truly understand their pain. My experience has given me resources and the ability to connect with people facing this monstrous disease. It’s also given me the opportunity to lead clients down a path different from my own: one where they feel empowered to get the information and support they need from their medical team, where they have someone who understands what they’re going through to help them process the experience as it unfolds. I can’t prevent the horrors of it, but I can be an empathic witness to their pain—and that gives me hope that I may be able to prevent them from developing PTSD, as I had.

I hope I can give clients a sense of the real picture I’d been missing, which runs counter to our cultural narrative that life should and will return to normal one day. Lots of people, including doctors and therapists, told me that if I could just get through treatment, I’d get my life back and be able to “put it all behind me.” I was told that, in a few years, cancer would just be a “blip” in my past. That hasn’t been true for me, and the unrealistic expectation that it could be set me up for trauma.

I want my clients to have hope that things will get better—I think that’s crucial for survival—but I also want them to know that better doesn’t mean “the way it was.” Life after cancer is different; I’m different. I fought this truth for a long time, but now I’m finding it easier to look forward, rather than back. If my experience lets me help others find their way here with less disappointment and suffering, maybe I’ll find meaning in cancer after all.

Let us know what you think at letters@psychnetworker.org.

Anna Lock

Anna Lock, PsyD, is the clinical director at Psychotherapy Networker.