Enjoy the audio preview version of this article—perfect for listening on the go.

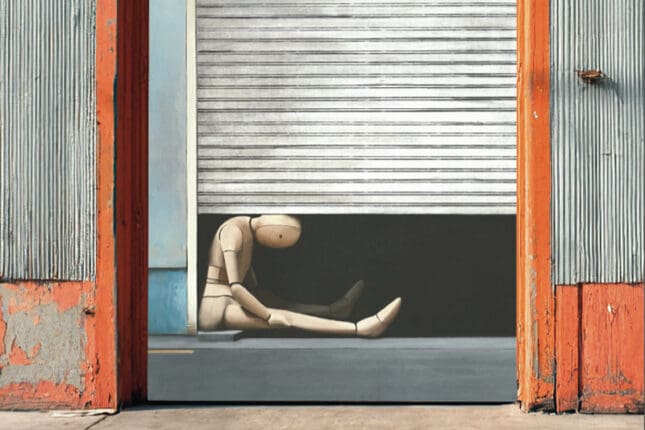

I want to die.

It was the summer of 2020, and this familiar, haunting thought I’d evaded for so long was now creeping back into my brain. I sat motionless on the couch as my dog, Phoebe, howled. My husband had just left to pick up groceries that I’d obsessively wipe down the moment he got home. I glanced at the clock. I had a client session in 20 minutes, followed immediately by supervision with one of my staff members.

My own time in therapy had taught me to recognize suicidal ideation as a sign that I felt trapped in circumstances that seemed inescapable—and that I needed to get help. But I couldn’t do that right now; my client and supervisee needed me. Inhale for four seconds, hold for seven, exhale for eight, I told myself, remembering one of the grounding skills I’d learned over the years. After a few minutes, I stood up, walked down the hall to my home office, logged in for my session, and tucked the fear and overwhelm away for later.

The truth is that I was in the middle of a silent crisis, one that many other therapists are facing alone. Do we push down our own struggles to keep working, or do we recognize that our own healing and professional competence are inextricably linked?

After I saw my last client of the day, I decided to pick up the phone to call for help, but my head spun with all the reasons why I couldn’t check myself into residential treatment: I won’t be able to prep for teaching this fall! What will my clients do without me for four weeks? How will I run payroll without access to my computer? Like so many therapists, my identity was rooted in being a helper. Who am I, I wondered, if I’m not helping my clients or my staff?

Ultimately, I’m glad I made that phone call and got help. But what if I hadn’t? What if, like so many therapists, I’d simply continued to compartmentalize and medicate my overwhelm with wine and Netflix, telling myself this was just part of the job? How long before the problem would’ve boiled over? How long before my work—and my clients—would’ve suffered for it?

Sadly, my experience is hardly unique. Therapists are experiencing the same collective trauma as their clients around unprecedented political polarization, climate change, and economic uncertainty. It’s impossible for us not to feel fear and anxiety. I hear about these feelings again and again not only when sitting with clients, but in my conversations with supervisees, consultees, and online therapist communities.

In 2023, the National Council for Mental Wellbeing reported that 93 percent of mental health professionals are experiencing burnout, 62 percent classify this burnout as moderate or severe, and 48 percent have considered leaving the field as a result. But graduate school didn’t prepare us to manage feelings of overwhelm. And at no point in our careers has any modality, course, or conference really taught us how to survive when it feels like the world is falling apart. We’ve been trained to help others heal while remaining strangers to our own healing.

What so many of us really need goes beyond individual self-care. It will take reimagining our training. It will take learning not only how to heal others, but learning how to heal ourselves. Instead of sitting in pain and isolation, it will take creating places where we can congregate, acknowledge our shared experience, and get support.

The Wounded Healer

In the 1980s and ’90s, a handful of studies compared therapists’ mental health to the general population. A later meta-analysis suggested that therapists are twice as likely to have experienced trauma or mental illness than their nonclinical peers. Indeed, many therapists were drawn to this profession not in spite of their wounds, but because of them. I was one of them.

When I entered graduate school, I knew something was wrong with my family, but couldn’t put my finger on it. For two hours a week, my classmates and I would sit in a stuffy, windowless room watching video clips of clinical gurus like Minuchin, Aponte, and Satir. One week, we were tasked with creating family genograms that we’d later present to the class. When I got to work, I started unpacking everything that had felt wrong about my family—the communication styles, family rules, and patterns of mental illness. But when the time came for us to present, my heart began to race.

I watched as student after student took their spot at the front of the room and talked about their seemingly “normal” families. Sure, there was some anxiety, or depression, or addiction here and there, but their stories seemed otherwise unremarkable. My face began to grow hot. Is my family the only one that’s completely screwed up? I wondered. How can I possibly talk about my family without crying in front of the whole class?

Fortunately, I wouldn’t be presenting until the following week, so I had some time to get my bearings. Our professor, Dr. Friere, was one of my favorites—a spitfire, badass of a woman with wisdom and heart. After class, I approached her with tears welling in my eyes and told her my concerns.

“If it would help, you don’t have to face the class,” she said. “You can just present to me, and not look at anyone else.”

Her offer, while kind, highlighted exactly what was missing in my training: lessons about how to be present with intense emotion, stay authentic when triggered, and sit in uncertainty.

I didn’t take Dr. Friere up on her offer, and the following week, holding my poster board marked with squiggles, half-colored squares, and circles indicating strained communication, addiction, and mental illness, I let the tears fall.

Here I was, learning about family systems while experiencing toxic family dysfunction in my own life. Maybe my classmates had been able to detach from any lived experience of dysfunction, but what about those of us who couldn’t? Where was the curriculum to help us learn to process our demons?

Leaning into Our Humanity

Our profession needs clinicians who have lived experiences of trauma and mental illness. After all, our clients deserve the type of knowing empathy that comes from walking in their shoes. But if so many therapists are drawn to the profession due to their own wounding, why don’t we talk about this in our training? Without learning how to do our own work, how can we expect to show up fully for our clients? Sometimes we must learn as we go, as I did with my client Jennifer.

One day, Jennifer sat down in my office and began listing all the existential threats compounding her baseline anxiety: the political rancor, war overseas, and climate change. How do I tell her I’m grappling with these things too, I wondered, without worsening her anxiety?

As she gazed at me with a combination of panic and desperation, scanning my face for a shred of hope, I knew that no amount of reassurance could soften her dread. It’s said that we can only take our clients as far as we’ve taken ourselves, and if we can’t lean into our own existential fears, powerlessness, and grief, we can’t help our clients do the same. Maybe, I thought, helping Jennifer right now lies in my own willingness to face these realities not as a neutral professional, but as a fellow human being.

Rather than jump into the anxiety with her, I decided to lean back and notice the pressure I’d been feeling to find a solution. “What would it be like for you to know that I’m holding the same fears and anxieties as you?” I asked.

We spent the rest of the session exploring the experience of being two humans connected not only by our fears and anxieties, but also by our grief and desire for a better world.

“I feel a little more calm and hopeful now,” Jennifer told me as our session came to a close. Truth be told, I felt better too.

The Revolution Starts Now

Of course, simply disclosing to clients that we’re experiencing many of the same anxieties they are isn’t a reliable solution for combatting burnout in our profession. Change needs to happen on an institutional level. Our field needs to help early career therapists process their own suffering. We need to create systems that support mid-career therapists too, who too often feel isolated and overwhelmed as I did.

I truly believe that we’re at an inflection point where we have an opportunity to change the course of our field. Rather than getting trapped in fear and overwhelm, we can choose the antidote: taking collective action and dreaming of a different future for this profession.

How? You can start by simply finding a quiet place to sit. Allow your imagination to expand and flow, inviting creative energy to move through you. Ask yourself: If I could design a psychotherapy training program that would’ve suited my personal growth and learning needs, what would that look like? What inspires me to help not only my clients, but myself? How can licensing boards, academic institutions, professional organizations, and workplaces better suit not just my professional development, but my personal development as well?

As you ask yourself these questions, notice what excites you, what scares you, what feels possible, and any other ideas that come to mind. As you contemplate these questions, write down what arises. These thoughts don’t have to be practical. They don’t even have to make sense. The next chapter of psychotherapy won’t be written by a single person or idea. Instead, over time, our collective intentions will coalesce into actionable steps.

I pondered these questions on a recent Sunday afternoon and came up with a list of my own hopes for the field. Here’s what I wrote.

Rethinking training programs: Imagine that therapy was mandatory and free for students in all social work, counseling, therapy, and psychology programs. Programs would be a combination of didactic and experiential learning, where students would discover how to examine their own mental health experiences while supporting clients. Programs would also offer parallel training labs where students could process personal material that’s triggered by coursework. Small cohorts could meet throughout the program to support one another to integrate academic material into their personal journey.

Rethinking supervision: A profound opportunity for revolution lives in the supervision space. Envision reflective supervision as the norm, where case consultation covers not only how to treat clients, but also addresses the therapist’s internal experience. This internal reflection helps new therapists notice how they may be impacting the therapy session. Parallel process is an expectation of supervision as we normalize growing alongside our clients. Emotional responses are seen as a natural part of supervision and revered. Group supervision evolves into support groups where clinicians learn the value of holding one another in our own processes.

Rethinking professional development: Suppose conferences included personal growth tracks that focus on therapist self-awareness and personal growth, not just techniques to help our clients. Therapist meet-ups become staples, safe spaces to process how we’re being impacted by our work. Regular retreats combine professional learning with personal healing.

Community-building: Imagine a return to apprenticeships, where experienced mentors shape new clinicians. Each new graduate would be connected with an experienced clinician who offers support, advice, and caring reflection. Local therapist networks band together to share information and resources for running a business, getting client referrals, and taking collective action on policy decisions.

Systemic changes: Micro changes become macro shifts, as licensing boards require ongoing personal work, not just CEs. Therapists automatically receive full insurance coverage for their own therapy. Workplaces regularly screen for burnout and encourage asking for help. Our professional organizations model professional vulnerability and self-work as part of our initial learning and continued development.

The Healing Ripple Effect

“Do you think I can go where you went for treatment?” my supervisee asks timidly, her voice quivering through tears. We spend an hour on the phone as she debates with her ambivalent parts. The stress of working through the pandemic while living alone has activated her childhood trauma, and she’s just told me she feels like dying. I share my experience, strength, and hope without making false promises. We create a plan for her clients, so she can focus on her own healing.

Next year, her supervisee will ask the same question and find her way to treatment as well.

Sharing our vulnerabilities and traumas can inspire others to ask for help. And if we shift our professional culture to center our own support and growth, we can end so much needless suffering. Our clients will undoubtedly benefit as well. When therapists heal, everyone wins.

But right now, we don’t have the systems in place to revolutionize therapy training and development. This will take an abundance of courage, hope, humility, and compassion, as well as a shared understanding about what it means to center our healing. It will take time. History shows that most revolutions don’t happen in a single moment; they progress one person at a time. When a clinician changes how they supervise, a professor expands their curriculum, or a small group of therapists creates a weekly meet-up, then change begins to ripple outward.

As the ground becomes more solid beneath our feet, our clients will begin to experience more hope as well. They’ll build the capacity to work toward the common good. And the more this happens, the more our systems will start to reflect the values that we therapists know make for healthy communities.

In the meantime, here’s my invitation to you: Don’t be afraid to take your own healing journey, whatever that may look like. Chances are doing so will make you a better therapist, leader, and teacher. Don’t neglect your pain. It connects us with the humanity of our clients and with each other. Try to make a small shift in your practice, teaching, or supervising. And when you do, take note of what changes and share it with your colleagues. This is how we start the revolution. First inward, then outward, one step at a time.

Sarah Buino

Sarah Buino, LCSW, is a visionary therapist, consultant, and speaker dedicated to transforming the healing professions by integrating clinical expertise with grounded business strategy. As founder of Head/Heart Therapy, Inc., Head/Heart Business Therapy, and Group Practice (R)evolution, she supports therapists in aligning their personal growth with professional impact. Through her podcast Conversations With a Wounded Healer, Sarah explores how our own healing journeys shape how we serve others.