This March, poet, storyteller, and philosopher David Whyte will once again be the keynoter at the annual Networker Symposium. But what does a non-therapist like him have to say to an audience of clinicians? From Whyte’s perspective, psychology and psychotherapy simply don’t go far enough. Their focus is restricted to the individual’s biography—good for a start but, according to Whyte, too small an arena for the capacious human soul. As he once said, “There’s something beyond your biography in a more soul-based view of existence that helps you make sense of your individual life in a way that psychology can’t do.”

In Consolations, his most recent book, Whyte offers meditations on 52 ordinary words to shift and broaden their meaning, taking them to the edge of revelation and discovery. As always, he seeks to bring us into the Big Story and jog us awake as if to say, “Open your eyes! Watch! Listen! Smell! Pay attention!”

If you can’t make it to this year’s Symposium, here’s the next best thing: some excerpts from Consolations to take you beyond the edge of your familiar, known world.

***

Courage is a word that tempts us to think outwardly, to run bravely against opposing fire, to do something under besieging circumstance, and perhaps, above all, to be seen to do it in public, to show courage; to be celebrated in story, rewarded with medals, given the accolade, but a look at its linguistic origins is to look in a more interior direction and toward its original template, the old Norman French, Coeur, or heart.

Courage is the measure of our heartfelt participation with life, with another, with a community, a work; a future. To be courageous is not necessarily to go anywhere or do anything except to make conscious those things we already feel deeply and then to live through the unending vulnerabilities of those consequences. To be courageous is to seat our feelings deeply in the body and in the world: to live up to and into the necessities of relationships that often already exist, with things we find we already care deeply about: with a person, a future, a possibility in our society, or with an unknown that begs us on and always has begged us on. To be courageous is to stay close to the way we were made.

The French philosopher Camus used to tell himself quietly to live to the point of tears, not as a call for maudlin sentimentality, but as an invitation to the deep privilege of belonging and the way belonging affects us, shapes us, and breaks our heart at a fundamental level. It is a fundamental dynamic of human incarnation to be moved by what we feel, as if surprised by the actuality and privilege of love and affection and its possible loss. Courage is what love looks like when tested by the simple everyday necessities of being alive.

Parenthood is a timeless test of courage and alignment. To be a new mother or father and live up to and into the overwhelming power and helplessness of that new love is to be heartfelt, to be courageous, just by the fact of being shaken and realigned with a new and surprising life, come from nowhere. The first courageous step may be firmly into complete bewilderment and a fine state of not knowing.

As new parents we may not even know what the word parent means, we may not know what to do or how to get through, we live literally to the point of tears and fears, our own and our child’s. There is no enemy line to throw ourselves at, no medal to be earned. The interior template of courage shows itself slowly, imperceptibly, the interior psyche settling and seating itself into a relationship with a future that chooses as its foundation a new and unknown child. From the outside we see only someone walking along the street, heavily pregnant, or pushing a stroller, weighted by the bric-a-brac of parenthood, no glamor in the outward show, deserving of no medal, but on the inside, a heartfelt, robustly vulnerable and courageous realigning of one’s life with another. The beginning of a courageous bearing inside that will only later come to fruition on the outside.

As actual parents or not, we become courageous whenever we live closely and to the point of tears with any new possibility made known inside us, whenever we demonstrate a faith in the interior annunciations and align ourselves with the new and surprising and heartfelt necessities of even the average existence, to allow ourselves to feel deeply and thoroughly what has already come into being is to change our future, simply by living up to the consequence of knowing what we hold in our affections.

From the inside, it can feel like confusion, only slowly do we learn what we really care about, and allow our outer life to be realigned in that gravitational pull; with maturity that robust vulnerability comes to feel like the only necessary way forward, the only real invitation and the surest, safest ground from which to step. On the inside we come to know who and what and how we love and what we can do to deepen that love; only from the outside and only by looking back, does it look like courage.

***

Heartbreak is unpreventable; the natural outcome of caring for people and things over which we have no control, of holding in our affections those who inevitably move beyond our line of sight.

Heartbreak begins the moment we are asked to let go but cannot, in other words, it colors and inhabits and magnifies each and every day; heartbreak is not a visitation, but a path that human beings follow through even the most average life. Heartbreak is an indication of our sincerity: in a love relationship, in a life’s work, in trying to learn a musical instrument, in the attempt to shape a better, more generous self. Heartbreak is the beautifully helpless side of love and affection and is just as much an essence and emblem of care as the spiritual athlete’s quick but abstract ability to let go. Heartbreak has its own way of inhabiting time and its own beautiful and trying patience in coming and going.

Heartbreak is how we mature; yet we use the word heartbreak as if it only occurs when things have gone wrong: an unrequited love, a shattered dream, a child lost before their time. Heartbreak, we hope, is something we hope we can avoid; something to guard against, a chasm to be carefully looked for and then walked around; the hope is to find a way to place our feet where the elemental forces of life will keep us in the manner to which we want to be accustomed and which will keep us from the losses that all other human beings have experienced without exception since the beginning of conscious time. But heartbreak may be the very essence of being human, of being on the journey from here to there, and of coming to care deeply for what we find along the way.

Our hope to circumvent heartbreak in adulthood is beautifully and ironically childlike; heartbreak is as inescapable and inevitable as breathing, a part and a parcel of every path, asking for its due in every sincere course an individual takes, it may be that there may be not only no real life without the raw revelation of heartbreak, but no single path we can take within a life that will allow us to escape without having that imaginative organ we call the heart broken by what it holds and then has to let go.

In a sobering physical sense, every heart does eventually break, as the precipitating reason for death or because the rest of the body has given up before it and can no longer sustain its steady beat, but hearts also break in an imaginative and psychological sense: there is almost no path a human being can follow that does not lead to heartbreak. A marriage, a committed vow to another, even in the most settled, loving relationship, will always break our hearts at one time or another; a successful marriage has often had its heart broken many times just in order for the couple to stay together; parenthood, no matter the sincerity of our love for a child, will always break the mold of our motherly or fatherly hopes, a good work seriously taken, will often take everything we have and still leave us wanting; and finally even the most self-compassionate, self-examination should, if we are sincere, lead eventually to existential disappointment.

Realizing its inescapable nature, we can see heartbreak not as the end of the road or the cessation of hope, but as the close embrace of the essence of what we have wanted or are about to lose. It is the hidden DNA of our relationship with life, outlining outer forms even when we do not feel it by the intimate physical experience generated by its absence; it can also ground us truly in whatever grief we are experiencing, set us to planting a seed with what we have left or appreciate what we have built even as we stand in its ruins.

If heartbreak is inevitable and inescapable, it might be asking us to look for it and make friends with it, to see it as our constant and instructive companion, and perhaps, in the depth of its impact as well as in its hindsight, and even, its own reward. Heartbreak asks us not to look for an alternative path, because there is no alternative path. It is an introduction to what we love and have loved, an inescapable and often beautiful question, something and someone that has been with us all along, asking us to be ready for the ultimate letting go.

***

Honesty is reached through the doorway of grief and loss. Where we cannot go in our mind, our memory, or our body is where we cannot be straight with another, with the world, or with our self. The fear of loss, in one form or another, is the motivator behind all conscious and unconscious dishonesties: all of us are afraid of loss, in all its forms, all of us, at times, are haunted or overwhelmed by the possibility of a disappearance, and all of us therefore, are one short step away from dishonesty. Every human being dwells intimately close to a door of revelation they are afraid to pass through. Honesty lies in understanding our close and necessary relationship with not wanting to hear the truth.

The ability to speak the truth is as much the ability to describe what it is like to stand in trepidation at this door, as it is to actually go through it and become that beautifully honest spiritual warrior, equal to all circumstances, we would like to become. Honesty is not the revealing of some foundational truth that gives us power over life or another or even the self, but a robust incarnation into the unknown unfolding vulnerability of existence, where we acknowledge how powerless we feel, how little we actually know, how afraid we are of not knowing and how astonished we are by the generous measure of loss that is conferred upon even the most average life.

Honesty is grounded in humility and indeed in humiliation, and in admitting exactly where we are powerless. Honesty is not found in revealing the truth, but in understanding how deeply afraid of it we are. To become honest is in effect to become fully and robustly incarnated into powerlessness. Honesty allows us to live with not knowing. We do not know the full story, we do not know where we are in the story; we do not know who is at fault or who will carry the blame in the end. Honesty is not a weapon to keep loss and heartbreak at bay, honesty is the outer diagnostic of our ability to come to ground in reality, the hardest attainable ground of all, the place where we actually dwell, the living, breathing frontier where there is no realistic choice between gain or loss.

***

Shadow does not exist by itself, it is cast, by a real physical body. We may say a person is overwhelmed by their shadow: a Tiger Woods by their sexuality, a Richard Nixon by their overweening sense of power, a nation by its hubris, but their shadow is passive, an absence of light, a shape lent by their own outline. Shadow is shaped by presence; presence comes a priori to our flaws and absences. To change the shape of ourselves is to change the shape of the shadow we cast. To become transparent is to lose one’s shadow altogether, something we often desire in the spiritual abstract, but actually something that is not attainable by human beings – to change the shape of the identity that casts a shadow is more possible. Shadow is a necessary consequence of being in a sunlit visible world, but it is not a central identity, or a power waiting to overwhelm us.

Even the most beneficial presence casts a shadow. Mythologically, having no shadow means being of another world, not being fully human, not being in or out of this world. Shadow is something that must be lived with, literally, as it follows us around, obscuring the sun or the view for others, yet we cannot use it as an excuse not to be present, nor to act, nor to effect others by our presence, no matter if the effect is sometimes indeed, overshadowing or difficult. Nor can we use it as an excuse to run uncaring over other’s concerns.

To live with our shadow is to understand how human beings live at a frontier between light and dark; and to approach the central difficulty, that there is no possibility of a lighted perfection in this life; that the attempt to create it is often the attempt to be held unaccountable, to be the exception, to be the one who does not have to be present or participate, and therefore does not have to hurt or get hurt. To cast no shadow on others is to vacate the physical consequences of our appearance in the world. Shadow is a beautiful, inverse, confirmation of our incarnation. Shadow is intimated absence; almost a template of presence. It is a clue to the character of our appearance in the world. It is an intimation of the ultimate vulnerability, the dynamic of being found by others, not only through the physical body but by its passing acts; even its darkening effect on others; shadow makes a presence of absence, it is a clue to ourselves and to those we are with, even to the parts of ourselves not yet experienced, yet already perceived by others. Shadow is not good or bad, only inescapable.

***

Solace is the art of asking the beautiful question of ourselves, of our world or of one another, in fiercely difficult and un-beautiful moments. Solace is what we must look for when the mind cannot bear the pain, the loss or the suffering that eventually touches every life and every endeavor; when longing does not come to fruition in a form we can recognize, when people we know and love disappear, when hope must take a different form than the one we have shaped for it.

Solace is the beautiful, imaginative home we make where disappointment can go to be rehabilitated. When life does not in any way add up, we must turn to the part of us that has never wanted a life of simple calculation. Solace is found in allowing the body’s innate wisdom to come to the fore, the part of us that already knows it is mortal and must take its leave like everything else, and leading us, when the mind cannot bear what it is seeing or hearing, to the birdsong in the tree above our heads, even as we are being told of a death, each note an essence of morning and of mourning; of the current of a life moving on, but somehow, also, and most beautifully, carrying, bearing, and even celebrating the life we have just lost. A life we could not see or appreciate until it was taken from us. To be consoled is to be invited onto the terrible ground of beauty upon which our inevitable disappearance stands, to a voice that does not soothe falsely, but touches the epicenter of our pain or articulates the essence of our loss, and then emancipates us into both life and death as an equal birthright.

Solace is not an evasion, nor a cure for our suffering, nor a made-up state of mind. Solace is a direct seeing and participation; a celebration of the beautiful coming and going, appearance and disappearance of which we have always been a part. Solace is not meant to be an answer, but an invitation, through the door of pain and difficulty, to the depth of suffering and simultaneous beauty in the world that the strategic mind by itself cannot grasp nor make sense of.

To look for solace is to learn to ask fiercer and more exquisitely pointed questions, questions that reshape our identities and our bodies and our relation to others. Standing in loss but not overwhelmed by it, we become useful and generous and compassionate and even amusing companions for others. But solace also asks us very direct and forceful questions. Firstly, how will you bear the inevitable that is coming to you? And how will you endure it through the years? And above all, how will you shape a life equal to and as beautiful and astonishing as a world that can birth you, bring you into the light and then just as you are beginning to understand it, take you away?

***

Vulnerability is not a weakness, a passing indisposition, or something we can arrange to do without, vulnerability is not a choice, vulnerability is the underlying, ever present and abiding undercurrent of our natural state. To run from vulnerability is to run from the essence of our nature, the attempt to be invulnerable is the vain attempt to become something we are not and most especially, to close off our understanding of the grief of others. More seriously, in refusing our vulnerability we refuse the help needed at every turn of our existence and immobilize the essential, tidal and conversational foundations of our identity.

To have a temporary, isolated sense of power over all events and circumstances, is a lovely illusionary privilege and perhaps the prime and most beautifully constructed conceit of being human and especially of being youthfully human, but it is a privilege that must be surrendered with that same youth, with ill health, with accident, with the loss of loved ones who do not share our untouchable powers; powers eventually and most emphatically given up, as we approach our last breath.

The only choice we have as we mature is how we inhabit our vulnerability, how we become larger and more courageous and more compassionate through our intimacy with disappearance, our choice is to inhabit vulnerability as generous citizens of loss, robustly and fully, or conversely, as misers and complainers, reluctant and fearful, always at the gates of existence, but never bravely and completely attempting to enter, never wanting to risk ourselves, never walking fully through the door.

Excerpted with permission from Consolations: The Solace, Nourishment and Underlying Meaning of Everyday Words ©2014 Many Rivers Press.

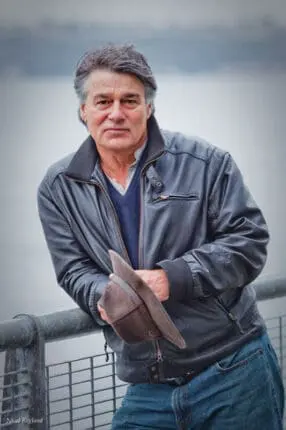

Photo © Nicol Ragland

David Whyte

David Whyte, Hons, poet, author, and internationally acclaimed speaker, is the author of eight books of poetry and four books of prose, including Consolations: The Solace, Nourishment & Underlying Meaning of Everyday Words.