You’re watching that series again?” my spouse asks, passing through the living room where I’m huddled on the couch with a box of Kleenex. “How many times is this?”

“I don’t know,” I confess. “Three?” I love watching stories about psychological healing in which there’s no therapist present. They showcase a type of resilience that’s organic to humans and that sometimes we therapists forget is there in the midst of all our fancy techniques and inventions.

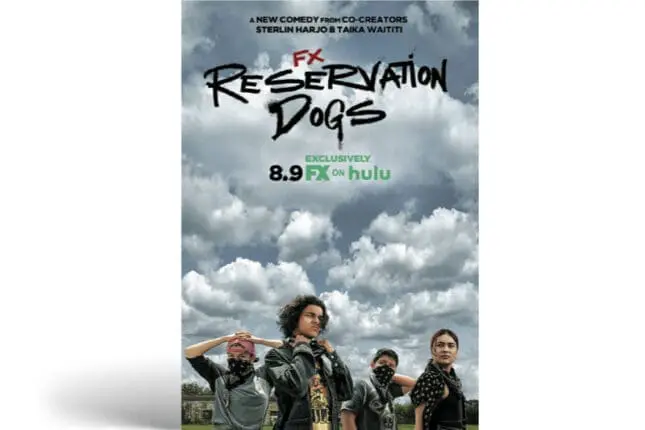

The award-winning FX series Reservation Dogs, which concluded last year after three seasons, is more than another heartwarming comedy-drama about teenage friends, like Derry Girls or Sex Education, which I also loved and watched more than once. It’s more than another brilliantly acted, expertly scripted, character-driven story about the coming-of-age journeys of hardscrabble but adorable youth. As a psychotherapist who’s treated trauma survivors for over three decades—steeped in the rational-empirical constructs of a white, Western medical establishment—the stories of Bear Smallhill, Elora Postoak, Cheese Williams, and Willie Jack Sampson have taught me something about the power of community, myth, and spirituality in healing trauma. These Indigenous characters and their beloved elders reframe our relationship to past and future, a shift essential to trauma healing that many Western-trained therapists like me often miss.

“This is Daniel,” 16-year-old Bear tells us in the first episode, gesturing toward a photograph of a smiling teenage boy. Played by D’Pharaoh Woon-A-Tai, Bear is the self-appointed ringleader of the Rez Dogs. “He died last year. We’re having a memorial for him in a couple days. RIP MY DAWG.”

Contemporary conventions of storytelling—what The New Yorker’s Parul Sehgal has called the trauma narrative—sets us up to expect that the story we’re about to enter will unfold from Daniel’s suicide and its effects on the surviving Rez Dogs. But Reservation Dogs overturns those expectations.

“This place killed him,” Bear adds, referring to Okern, the impoverished reservation town in the Muscogee Nation in Oklahoma, where the Rez Dogs live. “That’s why we’re saving our money, so we can leave this dump before it kills us too.” The show, then, is not about an isolated tragedy affecting one individual, but about the youths’ relationship to place and history. Daniel’s suicide—likely compounded by a struggle with bipolar disorder, inadequate healthcare, and his parents’ tumultuous marriage—was one of many effects of the brutal history that landed him, and all of the Rez Dogs, in Okern: the government betrayals, the forced relocations, the Trail of Tears, the boarding schools, a long unacknowledged history of genocide and cultural erasure. Daniel’s death wasn’t a mental health crisis. It was a crisis of history, the nightmare from which the Rez Dogs are trying to awaken.

Despite this underlying darkness, the youths embark on a series of mischievous, often hilarious, money-making scams—at one point, they hijack a Doritos delivery truck, which they try to sell—to escape to California, which was Daniel’s unrealized dream. Along the way, they grapple with their identities and relationship to a community they initially think is out to destroy them.

How do we free ourselves from the traumatic legacies into which we’re born? Androgynous Willie Jack, the Rez Dogs’ healer-in-training, portrayed with surly deadpan by Paulina Alexis, seeks out her community’s elders for guidance. Against her parents’ wishes, she braves a visit to the prison, with its metal bars and brusque guards, where Hokti, her aunt and Daniel’s grieving mother, are incarcerated. While Willie Jack awaits clearance to visit, an old man with a handlebar moustache and a cowboy hat speaks to her. (She later discovers he’s the first of many spirit visitors.) “The people who built this [prison] had lost their way,” he tells her. “It’s a travesty to take people away from their families and communities.”

Hokti (brilliantly acted by Lily Gladstone) is an angry, cynical medicine woman, who’s being frequently visited by a ridiculously cheerful spirit urging her to rise to the occasion of Willie Jack’s need.

“I just feel like we’re broken up,” Willie Jack tells Hokti as they sit in the concrete visiting room. “We’re supposed to be the dream team. Fuckin’ Rez dogs. It’s like everyone is walking around in the sunshine. But we’re just in the darkness.” Willie Jack is the first to reframe that Daniel’s death did not happen to one of them, an individual injury, but to all of them. She misses her friends. She longs for the easy camaraderie they had before the loss of Daniel. She doesn’t know how to make things right.

After Willie Jack offers Hokti snack food from the vending machine—the episode is called “Offerings”—Hokti, dressed in green institutional garb, leads her in breathing and prayer. “Remember the stories I told you when you were growing up,” Hokti reminds her, holding out her hands. “Generations of medicine people, caretakers. These are the ones who held us as we arrived from our homeland, the healers who carried us and buried us as we marched.”

It’s a chilling scene. It’s as if history comes into the room. As Willie Jack closes her eyes and breathes, a cadre of Muscogee ancestors encircle her, gazing down with kindness—so unexpected in the spare gray environment of the visiting room patrolled by scowling guards. One of the spirits puts her hand on Willie Jack’s shoulder. “Oh shit,” she says, tearing up.

“You don’t need me,” Hokti tells her niece. “You have them. This is the power we carry.”

Watching this scene of spiritual intergenerational connection, I found myself wondering what would happen if Willie Jack had taken her sadness and confusion to a Western-trained psychotherapist. Would she have been given medications, grief counseling, or EMDR? Not that those modalities wouldn’t have helped her, but what would she have missed? That connection to community, both living and in spirit; that sense of her suffering unfolding within greater forces of history; and a reminder of the power of her ancestors’ love, which has gotten her to this place, alive.

Indigenous myths offer another portal to healing. After the botched scramble to California, Bear separates from the Rez Dogs, lost and famished, a thousand miles from home, without even a charged cell phone. Seeking water at a roadside diner, he encounters a mysterious smiling woman (Kaniehtiio Horn), who offers him cherry pie. When he notices her hooves, he realizes he’s talking with Deer Lady. In Indigenous lore, this figure—part woman, part deer—seeks revenge against any man who hurts women and children. “Are you really real?” he asks. “I thought it was a story to keep uncles in line.”

“Yeah, well some uncles need more than stories to keep them in line,” Deer Lady tells him grimly. “Those are the ones I visit.”

“Are you gonna kill me?” Bear asks her.

In a series of flashbacks, Deer Lady recalls the tragedy of Catholic boarding schools, where Indigenous children were taken from their communities, held hostage, forbidden to speak their language, physically and mentally abused, and often killed and buried in unmarked graves—all at the hands of nuns and priests. Deer Lady holds on to memories of lost children, especially one boy, her friend, who was murdered by a man named James Minor. “You remind me of a boy I once knew,” she says, “I’ll take you home.”

On the way back to Okern, Deer Lady stops at the ranch of James Minor, now an old man with reduced faculties, and goes inside his house. “Did you kill someone?” Bear asks fearfully when she returns. “I killed a human wolf,” she answers unapologetically, her fur coat stained with blood. Indeed, rage has a role in healing from historical injustices—which may make some white people uneasy, but Bear gets it. “You’re going to be okay, Bear,” she tells him after she’s driven him home. “And don’t you worry about becoming [a bad man like] your dad. Your mama saw to that.”

We therapists trained in the dominant-culture construct of healing tend to view trauma as discrete catastrophic events that happen to individuals in a linear fashion: before, BAM!, then after. We join our clients during after and focus on establishing safety, expanding coping skills, facilitating catharsis, and enabling meaning-making. If we’re successful, our clients integrate the experience into an expanded sense of self, become asymptomatic, and move on.

Reservation Dogs has paradigm-shifting lessons about how humans heal from soul-robbing tragedies. It recasts healing as something that evolves over time and generations, not an individual life. Imagine the relief if our clients realized they didn’t have to resolve all their suffering in a single lifetime, that they’re just intended to do a piece of the work in a long, historical progression. This Indigenous perspective invites people seeking healing to open their awareness to dreams, archetypes, and ancestral spirits, who light the way toward freedom, if we can open ourselves to their messages.

By the end of the series, none of the Rez Dogs leave Okern, although, with the help of elders, spiritual ancestors, and other mythic visitors, they grow into a deeper appreciation of community and their traditions. It’s not individuals who heal, but communities. “It’s how community works,” Hokti tells Willie Jack during another prison visit. “It’s sprawling. It spreads. The thing about community is, you gotta take care of it. You have to play your part.”

Wayne Scott

Wayne Scott, MA, LCSW is a psychotherapist and writer in Portland, Oregon. His memoir, “The Maps They Gave Us: One Marriage Reimagined,” about a couples’ adventures in marital therapy, is available at: https://www.waynescottwrites.com/.