This article first appeared in the May/June 2006 issue.

Rabbi Isaac Kramer walked slowly into my office, looking stiff and drained. His long, wavy hair was disheveled, and he was clad in a khaki army jacket and heavy work boots, a full keychain hanging from his belt. Tall and lanky, he was bent to the right to balance a heavy shoulder bag overflowing with books and files. He looked worn out, and his clothes gave him the appearance of a graying, 48-year-old Boy Scout.

He introduced himself: “I’m bipolar.” He went on to give me a lengthy history of his “mental illness.” His lethargy, I soon learned, was from the cocktail of medications he was taking, including high dosages of Lithium, Prozac, and Ambien. He described periods of severe depression since adolescence and a progressive deterioration of his condition in the last 20 years. At the time of our first meeting he was living a marginalized life, and his identity had become that of a professional mental patient.

Kramer had been in four long-term psychoanalytic treatments with different psychiatrists and an additional one-year course of cognitive-behavioral therapy. He’d been hospitalized several times, experimented with multiple combinations of medications, and was finally declared by his psychiatrists as having a “treatment-resistant depression.” As a result of his mounting psychiatric failures, in his last hospitalization, he was crowned with electroconvulsive therapy (ECT). Since the in-patient series didn’t eliminate his depressive episodes, he chose to continue receiving bilateral ECT maintenance treatments on a monthly basis and had been doing so for two years. The ECT left him with serious memory loss that he compensated for by writing himself reminders in a small notebook he carried in his shirt pocket.

By the time he’d come to see me, he’d been out of a job for 10 years and was living on disability and savings. He lived alone, was nearly cut off from his friends, and distant from his family. He’d never married and hadn’t had a conventional love relationship in decades. He spent his time reading, attending mood-disorder support groups, and going to classes and lectures on mental health or Jewish-related issues. He occasionally worked on community projects with his colleague, Bruce.

I was daunted by Kramer’s psychiatric history and puzzled about why my colleague Rebecca, who referred him to me, thought I could help him. I was concerned that he and I were an unlikely match. He’s religious; I’m secular. He’s American; I’m Brazilian. He was used to a remote, analytic type of therapy; I practice a conversational and interactive style. He often teased me about the spare, modern look of my office. An admitted pack rat, he lived with a year’s worth of magazines and old newspapers and piles of books everywhere. He could not part with his valuables, and lived with a sense of burgeoning chaos in his home.

In spite of our differences, we established a bond. What broke the ice, I believe, was that early in the therapy, Kramer made racy jokes about sexy Brazilian women in my waiting room and I cracked up, laughing with him. But, more important, he told me months later, I was the only therapist to show curiosity about the demise of intimate relationships in his youth and the mysterious disappearance of his sexuality. He told me that my persistence in asking about his romantic life, combined with my openness to his provocative sense of humor, was what allowed him to invite me into a secret world he’d never shared with anyone.

Kramer’s Life

The oldest of five children, Kramer described his father as a reticent stockbroker with a penchant for sudden rages. His immigrant Russian mother, who was loving but submissive, couldn’t protect him or his siblings from his father’s nasty put-downs. He learned to fend off his father’s criticisms by hiding in his room with a pile of science-fiction thrillers by his bedside. His maternal grandparents were his salvation. “Kramer, you’re the best,” his grandmother would say. His grandfather regaled him with Talmudic stories and carried him on his shoulders to the synagogue for daily prayer.

In spite of the oppressive tension in his house, Kramer remembered himself as a relatively happy child who was intellectually inquisitive and socially gregarious. He collected dossiers on every subject, from Greek mythology to birds in the Amazon, and surrounded himself with the girls in his neighborhood, leading them in games. He adored outings with the local Boy Scouts, and loved taking walks in the woods, spending hours observing the toads in a pond or watching the birds.

Kramer’s first bout of depression happened when he was 13, soon after his family moved to a new neighborhood. Away from his friends and his grandparents’ daily love, he felt inadequate and utterly alone. He started to believe in his father’s words: “You can fool people, but deep down, you’re lazy.” He was also dumbfounded by the changes in his body, thinking his sexuality was abnormal.

His love of learning earned him a place at an Ivy League University, but it was in college that his episodic depression began to take deep roots. He experienced enormous emotional turmoil and spent days alone in his dorm room under the bedcovers, reading Kafka and the existentialists. Nevertheless, with the help of a university counselor and his own self-determination, he finished college on time and fled to Israel to avoid the pressure of having to make major decisions about his future.

Kramer spent eight years in Israel. During the first few years, he lived in a kibbutz, and later went through traditional rabbinical training, at which point, his depression sneaked back again. He was conflicted about whether he should follow the progressive movements of that time or stay on the terra firma of conventional Judaism. He resolved his dilemma by heading back to the United States, where he took a position as a pulpit rabbi in a small conservative suburban synagogue in the Midwest, close to his hometown.

Kramer’s congregation valued him for his leadership and innovative programs. Two years into the job, however, he started having difficulties with board members and began suffering frequent periods of depression that lasted for weeks or sometimes months. At such times, he refused to get out of bed, eat, or answer the phone. Intermittently, he experienced periods of being overly excited, consumed by intellectual projects, and prone to telling sexualized jokes, which upset his traditionally oriented congregants. He was unsure if his “euphoria” was a side effect of medications or a part of his “mood disorder.” He couldn’t fall asleep at night and struggled to get out of bed every morning. After many years of repeating this pattern without relief, he felt it was best to leave his job.

The Secret World

The major turning point in our therapeutic relationship was when Kramer shared with me that almost every night, for the last seven years, he’d been making calls to a phone-sex operation in Colorado. He’d developed relationships with several women there, and in the last two years had fallen in love with Sherry, who told him she was an extremely attractive, 22-year-old graduate student in English who shared not only his erotic fantasies but also his interests in poetry and religion. He said that, initially, their interactions were mostly lustful but, as time went, they developed a deeper relationship. Kramer believed everything Sherry said, and one of her stories was that she’d been sexually abused by her father. Aware of her presumed vulnerabilities, Kramer sent her self-help books and newspaper clippings; to which she responded by sending him poems and cards. Their occasional fights added an even stronger sense of reality to their transactions, making the ebb and flow of their “intimacy” very exciting to him.

There was, however, one hitch in their “relationship”: Sherry wouldn’t break the rules for him. Whenever Kramer felt especially close to her, he’d insist that they meet in person. When she declined his invitations, he’d become angry and stop calling. Eventually, he’d miss her and call again. Kramer’s relationships with Sherry and with the other women were costing him many thousands of dollars.

Naturally, I was concerned that Kramer was being exploited, and I often tried to bring him back to reality. I’d say: “Kramer, even if Sherry cares about you, this is a commercial endeavor; it’s her job to hook you in” or, “Since she refuses to come and see you, why don’t you try real dating?” My attempts were met with firm resistance: “You don’t understand, Michele: Sherry loves me. Why don’t we have a three-way conference call so you can see for yourself what I’m talking about?” and “I am sure that sooner or later Sherry will come to visit me.” It was obvious to me that Kramer wasn’t psychotic, but he was caught in a deep trance that he couldn’t bear to give up.

I consulted with one colleague who insisted I should refer Kramer to Sexual Addicts Anonymous. Another thought I should consider additional medication for his “dysfunctional compulsive fetishism.” Yet I refused to reduce Kramer’s folly to another psychiatric symptom. Instead, I chose to understand his rapture as the expression of a lovesickness that might actually hold the key to his recovery.

As I listened to the details of Kramer’s encounters with Sherry, a new narrative began to emerge: I saw him thrown back in time, seeking to restore lost parts of himself and express his natural exuberance. He was enthralled: “Sherry is my soul mate” “She’s absolutely delightful . . . the best thing that ever happened to me.” Like an adolescent in love for the first time, he was animated and happy. He considered his “love affair” to be “not-so-kosher,” but he felt alive in ways he didn’t remember ever feeling. The phone-sex setting offered him a reliability that enabled him to take emotional risks and experience yearnings he’d suppressed for a long time. More than sex, Kramer craved emotional connection and the sense of community he experienced as he talked to the different “girls.” He also took great pleasure in being a mentor, often slipping into the role of rabbi and counseling them on values, education, and religion.

As the months went by, I began to witness dramatic and unexpected changes in Kramer. He began to question his psychiatric treatment and, with my encouragement, consulted with a psychiatrist who, to my relief, recommended he discontinue the ECT. Soon after that, Kramer also asked the doctor to stop all his psychotropic medications, so he could figure out what he actually needed. As he weaned himself off the drugs, he actually felt better. His memory began to improve, his body recovered its natural movements, and his face began to glow with a relaxed smile. By the time he finished making all of the medication adjustments, he hadn’t been depressed for more than a year and a half.

During this time, Kramer abandoned his Boy Scout uniform and began to dress like a grown-up. He cut his hair, shaved regularly, chose more fashionable glasses, and began to exercise and take care of his skin. He also became open to my coaching. Having opposed technology up until then, he got himself a computer and started corresponding with friends and acquaintances around the world. He also began to visit his family regularly and made efforts to interact more with his siblings, nieces, and nephews. His family members expressed pleasure in having him around and in seeing him so changed. He reconnected with old friends, who were happy to have him back. With one of them, Anne, he reestablished a close friendship, even telling her about his “love affair.”

Confronting Fantasyland

It was wonderful to see Kramer blossoming, but I continued to worry as he remained adamantly under the spell of his “love affair,” despite the open skepticism of his friends Anne and Bruce, and my own. I was concerned that his gullibility would lead to a disastrous disappointment, and that by staying in his fantasyland he was sabotaging his chances of developing face-to-face relationships with real, available women.

Then one evening two and a half years into the therapy, Kramer made a random call to the phone-sex agency and ended up talking to a new operator named Betsy. Feeling anguished, Kramer shared with her that Sherry refused to see him in person. Betsy, an unexpectedly honest and moral person, was appalled by his naivet[Cyrillic O] and confronted him harshly. “Kramer, this is a fantasy line,” she said, “and you’re delusional if you believe that what you hear is what’s real!” Knowing that Betsy was new to the business, he disqualified her comments and fought back. “You don’t understand, Betsy. Sherry and I have had a true, intimate relationship for over a year. She can’t afford to lose her job, but I’m sure that when she finishes school, we’ll get together.” Betsy took it upon herself to burst his bubble. Putting her job at risk, she gave him her home phone number so they could talk more openly. A few days later, the agency found out about her transgression and fired her.

Kramer was deeply touched that Betsy had put herself on the line for him. He felt very bad about her loss of income and insisted on compensating her for the trouble he’d caused. She refused, he insisted . . . and this back and forth launched their friendship. At this point I realized Betsy was my best ally and I asked Kramer to invite her to a joint therapy session. He welcomed the idea and flew Betsy into Chicago for our two-hour meeting, and to thank her, he treated her to a nice weekend in the city.

When Betsy came into my office, I saw a small, pale, thin woman in her mid-forties, with long, blond hair, casually dressed in jeans, T-shirt, and sneakers. A dropout graduate student, she supported herself building theater sets and with occasional jobs as a carpenter. She explained that she’d blown her cover because she was appalled by the agency’s lack of scruples when it came to Kramer. Of all the men she’d talked to, he had the worst case of confusing fantasy with reality, and she thought it was unconscionable to manipulate and exploit his vulnerability as they were doing. She revealed some of the details about the agency, describing the unglamorous cubicles they worked in, telling him that most of the women were in their forties rather than twenties, and discussing the elaborate methods and tricks they used to keep their customers calling.

After the session, Kramer took Betsy around the city. They talked for hours, but two moments were particularly sobering to him. While sitting in a caf[Cyrillic O], Betsy pointed out a large, middle-age woman with thick makeup and cheap jewelry and said, “she looks just like Tiffany,” one of the “girls” Kramer had talked to regularly. At another point, she cried about her own situation. Kramer, seeing her as a real person wounded by the harshness of life, found the last clouds of his spell dissipating. After the session and weekend with Betsy, he felt incapable of calling the phone-sex agency ever again.

The Aftermath

Like Rip Van Winkle, Kramer reemerged from 20 years of psychiatric fog and his Fantasy Island with a new sense of clarity about what was important to him. No longer subject to depressions, he pursued new friendships, strengthened his bond with Anne, started mentoring his teenage nephew, and took trips to see old friends in Israel. He got involved in a series of philanthropic projects that gave him great pleasure. He signed up for an Internet Jewish dating service and began to dabble in face-to-face dating. We both understood by then that fantasyland had been his rehearsal.

Several months after the session with Betsy, Kramer talked to me in the past tense about his folly: “I can’t believe how caught up I was, I know now I was delusional!”

I asked him, now that it was all over, what he understood about his rapture. “For most of my life, I lived in a bare desert, and then, suddenly, I came across an oasis,” he said. “I went wild; I couldn’t drink enough or eat enough fruits.” What was most important about his connection to Sherry and the others, he continued, was that he felt he could be a whole person, expressing all the parts of himself–he could express his sexuality, but also his soulfulness, and share his love of music, poetry, nature. He could even be a good rabbi. “I desperately wanted to rescue these girls, to save them from their bare lives.” For the first time, sex and love–always irreconcilable before–could come together. And he felt very strongly that, however false the situation and however deluded he was, he never would have been able to risk relationships in any other place.

He added that the fact that Betsy had had the courage to lose her job for him made it hard to maintain the fantasy. And he was grateful to me, too. “You normalized my experience as expressing my need to love and be loved, and to take pleasure in human intimacy. You had faith that I could get better, live a happier life.” He laughed. “You also kept saying: Kramer, stop treating yourself like a walking diagnosis. Come back to the world of the living!’ And here I am.”

Case Commentary

By Irvin Yalom

This remarkable story told in an authentic voice contains echoes of Bernard Malamud and I. B. Singer, great Jewish American writers of the past, and also of contemporary writer Steve Stern. A wonderful teaching tale, it conveys both the constricting power of irrational love and the healing forces of true caring and intimacy.

A powerful romantic infatuation has always perplexed and confounded the therapeutic enterprise. Some years ago, I began a book, Love’s Executioner, with the lines, “I do not like to work with patients in love. Perhaps it because of envy–I, too, crave enchantment. Perhaps it is because love and psychotherapy are fundamentally incompatible. The good therapist fights darkness and seeks illumination. While romantic love is supported by mystery and crumbles upon inspection.”

Love, that starry-eyed state of enchantment! Who doesn’t want it? And how do we deal with a patient in love? For such a long-suffering individual as Kramer, being in love is a blessing. He loses himself–his painful self-consciousness, his agonizing isolation from all other souls. In love, the long-suffering isolated “I” is dissolved into the warmth of the “we.” Kramer no longer is crushed by the pain of being himself.

Michele Scheinkman made herself accessible by doffing her role, by being natural, by laughing at Kramer’s jokes, by conveying her curiosity and caring. Soon Kramer sized her up as a safe person, with whom he could share his most secret world. But as Scheinkman heard about Kramer’s love for his phone-sex hostess, she began to worry. Obviously, her patient and his precious love were being exploited; his entire love affair was a chimera. Naturally, she couldn’t allow that and charged into action to protect Kramer by peeling him away from the lover who didn’t exist. Fortunately, she didn’t persist in the doomed adventure of trying to execute love, an endeavor that might have seriously mangled the therapeutic relationship. Instead, she took the wiser path of blessing, for the time being, the good, adaptive things that flowed from Kramer-in-love.

Then, along came Betsy, the hero of this tale, who had the determination, power, and credentials to burst the whole bubble. She didn’t shrink from the task. But she was so caring, so self-sacrificing, that Kramer listened to her as he would have to no one else. Kramer’s enchantment was broken, but he was left with a new set of possibilities: he now knew there was a world for him, a world that wasn’t desolate or arid, a world in which he could find love and a soul mate.

But Kramer, what’s this Internet dating nonsense?! This Betsy sounds like a nice lady. Sounds like the one for you. Go for her!

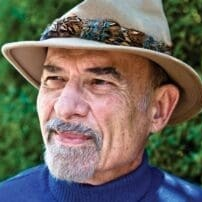

Michele Scheinkman

Michele Scheinkman, LCSW, is a faculty member of the Ackerman Institute for the Family and in private practice in New York City.

Irvin Yalom

Irvin D. Yalom, MD, is one of the world’s foremost psychiatrists, a visionary therapist and internationally bestselling author who has helped define the fields of group psychotherapy and existential therapy. His textbooks Theory and Practice of Group Psychotherapy and Existential Therapy remain standards for therapists in training worldwide, as does The Gift of Therapy: An Open Letter to a New Generation of Therapists and Their Patients. He’s also the author of the New York Times best-sellers Love’s Executioner, Momma and the Meaning of Life, Creatures of a Day, and Staring at the Sun: Overcoming the Terror of Death. A consummate storyteller, his teaching novels based in philosophical inquiry and psychological insight, including When Nietzsche Wept, The Schopenhauer Cure, Lying on the Couch, and The Spinoza Problem, have been best sellers in multiple countries. More at www.yalom.com