There are many lifetimes in a lifetime. I was born in the Ozarks in 1947 to parents who were just returning home from serving in the Navy during World War II. That puts me on the leading cusp of the Baby Boomer generation. I grew up in Beaver City, Nebraska, where my mother worked as the town’s doctor. I was the oldest child in a big family. We lived on the edge of town, and I spent my days reading or playing by Beaver Creek.

As a teenager, I was a socially inept, gawky girl. I went to the Methodist Church, where I earnestly signed a pledge never to drink, swear, smoke, or have sex outside of marriage. On my red record player, I played Broadway musicals, such as Camelot, South Pacific, and Flower Drum Song. Later, in high school, I listened to Dave Brubeck and Stan Getz and yearned for the day I could forever escape the Midwest.

After high school, I attended the University of California at Berkeley, during a time when it was a beacon for freedom and exploration of all kinds. My brother lived in San Francisco, and we saw the Grateful Dead and Janis Joplin in Golden Gate Park and at the Fillmore and Avalon. I took classes in Tarot reading and “Howling at the Moon” at the People’s Free University.

Since then, I’ve experienced other lifetimes, all in Nebraska—as a graduate student in psychology, as a mother of young children, and as the wife of Jim, a psychologist and musician. I’ve worked as a therapist, writer, and speaker. For the last 15 years, I’ve experienced the great privilege of being a grandmother with my five grandchildren living nearby.

There’s continuity among all these lives. I’ve always loved to be around family and close friends, to be outdoors, to take long walks, to swim, and to look at the sky. Ever since I was young, I’ve found comfort in reading, and I’ve always liked to take care of people and animals.

But I can also see great discontinuities. I can barely remember the girl who owned lacy baby-doll pajamas, danced the twist, and read her white leather Bible before turning out the lights and listening to KOMA. The young psychologist who scraped together money to buy an expensive suit for legal work feels like a stranger.

We boomers were children in the ’50s, teenagers in the ’60s, and college-age at the height of the Vietnam War. Now we’re in a new century, traveling down a new stretch of the river, aware of how vulnerable everything is, including ourselves.

We’re Getting Old

I always write about what I most want to learn, and, right now, I want to understand the implications of being a 70-year-old woman in this ageist and death-denying culture. I’m a sister, wife, mother, and grandmother. I’ve taught women’s studies, seen mostly women in therapy, and written about women. Much of what I explore applies to men, but I don’t claim great expertise on their developmental experiences.

The only constant in the universe is change. The one thing we can predict about our own lives is that they’ll be unpredictable. In this life stage, we’ll be beset by internal and external crises. If we’re like most of our peers, we’ll lose friends and family members. And, at least in small ways, our bodies will begin to betray us.

As we age, our bodies and relationships change, and the pace of change accelerates. At 70, we’re unlikely to be able to function as we did in our 50s. We require fresh visions, better navigational skills, and new paradigms for framing our experiences. What worked yesterday will not be sufficient for tomorrow.

Change may be gradual, but our realization of it comes in bursts. Ava’s watershed moment came when she was purchasing a ticket to the Chicago Art Institute. The young man at the desk asked her if she wanted the senior citizen discount. That wasn’t the usual response of men to Ava! She was a curvaceous brunette, who’d always been sexually appealing to men. How could this man see her as a senior citizen?

On one level, of course, she knew she was 65, but at the same time, she still saw herself as a gorgeous woman in her 30s. Her husband and many of the men she knew still treated her this way. It was strangers and newcomers who somehow couldn’t see the 30-year-old Ava. She was now completely invisible. She didn’t miss the catcalls as she walked down the street, but she didn’t like being erased.

The young man’s remark knocked her back a step. She put her hand to her heart and waited for her breath to return. Then she said that she wanted the discount.

There’s no one woman who can represent all of us. We’re partnered and single, healthy and infirm, and contented and miserable. Women our age vary by race, cultural background, employment, socioeconomic status, geographic region, and sexual preferences. Likewise, we range from women who are full-time caregivers to those who have no such responsibilities. We differ in our access to resources such as nearby family, a life partner, close women friends, a safe and connected community, affordable medical care, exercise facilities, and cultural opportunities. We vary in the amount of emotional and physical pain we’re suffering and in the amount of resilience we can summon. Some women seem hard to lift up, and others are impossible to keep down. Most of us exist between those extremes. We’re resilient on some days but not others. We recover quickly from one kind of stress, but struggle to bounce back after another. What we share is the distance we’ve traveled.

A developmental perspective on our 60s and 70s allows for a new openness in our hearts and minds. When we limit our belief in our own potential to grow, we also limit our incentive to grow. With the mindset that abilities, talents, and skills can be developed, every place we go becomes our school, and every person we meet becomes our teacher. The challenges and joys of this stage can be catalytic. If we stay awake and keep growing, we can see the love in our friends’ faces, taste the rain, and hear the song of the meadowlarks. We can do this even when we’re walking out of a funeral or in pain from arthritis.

Flourishing

Resilience isn’t a fixed trait, but instead can be learned in the same ways we learn to cook, drive, or do yoga. Growth doesn’t just happen. Some women remain locked in their smallest selves, cosseted by blankets of familiar but outdated ideas. Others wither emotionally over time and deal with life’s many body blows by becoming more isolated and self-involved.

As Marie von Ebner-Eschenbach, an Austrian novelist, wrote, “Old age transfigures or fossilizes.” We all have encountered someone who complains constantly, is critical of others, and is unskilled in self-awareness. Sometimes we are these women. We all get grouchy, blue, and make uninspired choices. We all lose battles with our appetites and impulses. However, it’s never too late for us to do better.

We can grow in moral imagination. This increased capacity for empathy comes from our own suffering and our witness of suffering. Pain drives us deeper and makes us kinder. It also toughens us up. We can learn to withstand the roughest of currents. We can be profiles in courage. This is not a theoretical point; I’ve seen this growth happen to my clients, my friends, and my family members.

All life stages present us with joys and miseries. Fate and circumstance influence which stage is hardest for any given individual, but attitude and intentionality are the governors of the process. This journey can be redemptive if we find ways to grow from the struggles our stage offers us. Just as adolescents must find their North Stars to guide them, so must we elders maintain clarity about the kind of people we want to be.

When transitions happen and identities change, one of our great challenges is to find a new sense of meaning and purpose in our lives. That sounds simple, but it isn’t easy. As my brother John observed when he was forced to retire for health reasons, “You can’t just go out and buy a pound of purpose.”

John was exactly right. We construct meaning when we choose what to do, how to help, and what stories to tell ourselves. Of course, in times of stress and change, even the busiest of us may want to luxuriate in sleeping in, coffees with our best friend, or watching movies any time of day. It’s a question of balance and contrast. We do best when we learn how to have both work and rest in our lives.

Our development is fueled by the need to adapt to new circumstances. Time passes so quickly that our lives feel as fading as jet contrails. We’re constantly engaged in a process of reflecting and problem solving. We ask questions such as, Now that I have time to travel, what do I want to do? Since my best friend moved to Arizona, whom do I call for a movie date? With my bad back, how do I carry in 30-pound containers of bird seed?

Simultaneously, we explore the largest of questions. Did I make good use of my time and my talents? Am I now? Was I loving? Am I now? Was I loved? Am I now? What is my place in the universe?

Many of us can describe our lives in both/and terms. In fact, that combination of suffering and happiness is what defines this life stage and fuels our growth. Suffering gives us empathy, while happiness gives us hope and energy. The contradictions of this life stage make it a portal for expanding our souls.

One of the great paradoxes of this life stage is that we experience not only the largest number of catastrophes, but also the highest well-being. Our contentment comes from acceptance of life as it is. Wisdom compensates for our travails. We can navigate the river’s snags, logjams, and downpours with competence and confidence. We can explore the mysteries along the shores of time. We can help each other travel down this river.

Wonder

The power of others to help me and my own power to find what I needed became crystal clear to me when I went on a retreat during the winter of 2017. During the week of Donald Trump’s inauguration as president, I attended a retreat at Ghost Ranch in New Mexico with noted Buddhist teacher Joanna Macy. She’d gathered together “earth protectors” to help us prepare for the future. We spoke of our fears, sorrows, and anger, and we heard a lot of terrible news about Mother Earth and climate change. We cried together, and we also danced and sang together.

One clear morning, we were encouraged to walk outside and look for something that spoke to us. Then we could sit down with that particular object and observe it carefully. After this, we were to design a small ceremony involving the object.

As I walked over the semi-frozen red dirt, I wore a heavy winter coat, gloves, and hiking boots. I could see the great Chama Valley, where the Tewa people had lived for centuries. A silver river wound through this valley and right up to Ghost Ranch. Rising above the valley were the blood-red, orange, and pink Sangre de Cristo Mountains, which looked exactly like Georgia O’Keeffe had painted them. High above them, the Pedernales Range was dusted with snow.

Two ravens were raucously squawking on a dead branch, and a flurry of wrens, like Christmas decorations, adorned a pinyon pine. Chamisa sagebrush sparkled in the sunlight. Almost everything spoke to me. But I walked on for a while, listening to my footsteps on the crunchy ground, breathing the pure mountain air, and wondering what my significant object would be.

As I approached Ghost Ranch’s labyrinth, I spotted it. Without any conscious thought, I knew this was it. The change in my breathing told me. On the high bank above the gurgling arroyo stood a large cholla cactus covered with bright yellow pears and thorns. Her pale green arms stretched Shiva-like in all directions. She was old and tattered, with some of her branches blackened and withered. At the same time, a few new appendages of a rich purple color were sprouting. That is exactly how I felt about myself. The starry-eyed high school girl, the young mother of a newborn, and even the woman who could ice skate and cross-country ski had perished. Yet I also could feel new, rich growth rising within me.

I sat on the cold ground by this battered cactus for some time. Behind it white clouds skittered by and disappeared. New clouds formed. After a while, the elements of my ceremony revealed themselves.

I pricked my finger with a thorn and offered my blood to all my ancestors and the ancestors of other living beings who had created this magnificence. I leaned over and gingerly kissed the top of a yellow pear.

I realized that this cactus with its withered arms symbolized what my life would be. It would consist of thorns and fruit, pain and beauty. My body would age, my soul would expand.

Sail On, Silver Girl

Generally, I don’t think about death during the day. I’m so busy with projects and people that I tend to think about what’s right before my eyes. When I go to the funeral of peers, I ponder their death and mine, but most of the time I’m thinking about life. Still, about once a month, I wake in the night and know with absolute clarity that I’ll soon be gone. This experience isn’t sad exactly; rather, it’s a feeling of deep awareness that opens a portal into my most reflective thinking.

I’ve always felt my own finitude. My father had his first stroke at 45 and died at 54. My mother died of diabetes at 74. I’d like to attend my last grandchild’s graduation from high school in 15 years and to meet at least one great-grandchild, but based on my family history, that’s unlikely. I’ve watched my diet and exercised regularly, but as we all know, there’s only so much we can do to combat our DNA.

Facing our own death offers us an opportunity to work with everything we have within us and everything we know about the world to create calmness and joy. As we approach death, we approach some of our greatest existential challenges and we face our greatest mystery.

I want to die young as late as possible. I want to die with dignity while I still have a high-quality life. I like myself as an active, engaged person with plenty of options for how I spend my time. When I’m sick, I don’t have the energy to control my overactive brain and thus, my mental health falls apart, along with my physical health. I grow depressed, self-critical, and overly worried about everything. Who wants to live that way?

I’d like to face death with the courage of my friend Betty Olson. When she had terminal cancer, she told her husband to respond to condolences in a certain way: to say that she’d experienced a rich, full life, wonderful friends, and a great family. She’d enjoyed the opportunity to give herself wholly and unreservedly to causes she believed in.

Betty lived a vibrant life almost until the end. She kept working on her causes, had friends and family come to visit, and stayed deeply curious about the world around her. Growing older never bothered her. She never lost her capacity for wonder.

If we’re lucky, we’ve been around people who were not afraid to speak openly about death. We’ve witnessed deaths of older friends and relatives and have learned from their examples. The experience of death and dying is what teaches us how to die.

A Jeffersonian Conversation

When I was speaking at a conference at the University of California, Los Angeles, I met a group of eminent psychiatrists, psychologists, and neuroscientists from all over the world. We were all invited to a dinner at an elegant home. The host was gracious; the other guests were people I’d admired all my professional life.

When we sat down to dinner, our host called us to attention. He said that he’d noticed that when a group like ours sat down to a meal, it would often fritter away the opportunity for a profound discussion by tablemates simply asking each other questions such as “How was your trip?” and “What’s the weather like where you come from?”

Our host suggested a Jeffersonian Conversation, so named because when Thomas Jefferson invited people to dine in his home, he’d pick a topic and ask everyone to tell a story related to that topic. That night our host picked what seemed like a rather macabre topic—death. However, we all were game to try, and soon we were swapping our stories and observations. I’ll remember that conversation for the rest of my life.

A portly, older psychiatrist from Germany said, “I’ve always wanted to die at the point I could no longer be useful. But I’m beginning to understand that old people have an evolutionary function. Our job is to take care of young people and help them be calm and happy.”

“I’m not crazy about dying. In fact, it scares the hell out of me,” said a banjo-playing neurologist from South Carolina. “I don’t want to leave my children or my grandchildren. They need us now, and I think they’ll continue to need us.” He continued, “I wish I could believe in the afterlife; it would be comforting to me.”

He told us about visiting his cousin who was an evangelical minister. This cousin was only a few weeks from death, but he was at home and comfortable and eager to talk. His cousin told him that not only was he unafraid of death, but in fact he was greatly looking forward to seeing the face of God. The neurologist said, “I envied him his faith.”

Several people talked about what they’d experienced in near-death situations. Because they were physicians, they’d often been near deathbeds. They all described people dying peacefully and with a sense of joy. Some people saw light, while others saw family members waiting for them. When people recovered from near-death experiences, they always said they’d lost their fear of death.

A trauma therapist from Colorado had recently lost her wonderful cello-playing husband and talked about his courage and grace as he said goodbye. She said that she felt his presence all the time. She knew they’re still deeply connected in spirit, and said that many people are afraid to die because they have no way to describe mystical or spiritual experience. But she knows that life doesn’t end with death. Relationships don’t end with death.

I said that while I’m not a particularly mystical person, I’ve had experiences that can only be explained as communication from departed loved ones. I told a story about my Aunt Grace. I’d always been especially close to her, and when I went to her little house in the Ozarks for her funeral, I noticed it was surrounded by flowers my cousins called naked ladies and I called surprise lilies. The next spring, surprise lilies popped up in my garden. I hadn’t planted them and they’d never come before. The year after that, these lilies popped up again, but in different places. After I moved to a new house, the “naked ladies” of changing locations continued to visit me every year. I can’t explain this in any rational way. In my heart, I feel as if it’s my Aunt Grace signaling me from the other side of the river. If I wanted to signal my family after my death, wouldn’t I do it with stars, flowers, or birds?

There was a great diversity of opinions about whether consciousness existed beyond the grave. But there was unanimity of opinion about what was important now.

We all agreed that we had at least this one precious life and that we wanted to love people, find pleasure and beauty, and do useful work while we were alive. All the people at that table felt grateful for the gift of life. We wanted to live exactly as long as we could feel that way.

Dying with Intention

Even in dying and death, we’re likely to have choices. Unless we die suddenly with no warning, we’ll have choices about whom to trust with our healthcare, medications, and invasive procedures. We can choose the people we want to be with and the place we want to die. Most importantly, we have choices about the attitudes we take toward the process.

Our fate is inevitable, but our attitudes are not. We can be cheerful or gloomy, solicitous of others or self-absorbed. We can approach our deaths with fear and resistance, or with curiosity and a sense of mission. Our choices determine how we die and how we and our loved ones feel about our crossing. Death offers us our last learning and teaching opportunity.

I’ve thought a great deal about how to have an intentional death, if I’m lucky enough to have that privilege. I’ve seen my parents and my husband’s parents die “bad deaths,” with months of suffering and too much medical intervention. I’ve been witness to deaths that I wouldn’t allow an animal to suffer.

I want to have time to say goodbye to my friends and family. I’d like some months to reflect on my impending experience. At the time of my death, I hope my family will be with me and that I can be looking outside at my familiar landscape. I want to be comfortable, aware, and not overly medicated.

I’ve done what I can to prepare for my death. I have a will, medical power of attorney, and medical directives. I’ve had many conversations with my family and my doctor about end-of-life decisions. My joking mnemonic device for them is, “If in doubt, snuff me out.”

I’m beginning to sort everything I own. I’m giving away things now that people would enjoy. I like making others happy and I’m no longer someone who cares much about stuff.

If I knew I had a month to live, I don’t think I would spend my time much differently than I do now. My everyday life is good enough for me. I might re-read my favorite books and listen to my favorite music. I’d try to be outdoors and see every sunset and sunrise. Who knows if I’ll get any of this, but it’s what I’m hoping for.

I love the world, but know I can’t stay. I’ll miss the beauty all around me. I’ve taken so much pleasure in the natural world, in people, and in books, music, and art. I’ll miss all that. But death is democratic: we all participate in its enactment.

And I’m making as many arrangements to assure that my wishes are fulfilled. I’ve written instructions for my funeral and selected the poems: Mary Oliver’s “In Blackwater Woods,” Jane Kenyon’s “Let Evening Come,” and Stanley Kunitz’s “The Long Boat.”

My daughter can give my eulogy, my minister son can lead the service. I’d like all my family members to be involved in some way. I want my husband’s band to play “Down by the River to Pray,” “Green Pastures,” and “A Wide River to Cross.” I want my Cousin Steve to sing, “Somewhere My Love.” He sang this at both of my aunts’ funerals. I do not want my funeral to be a celebration of life—funerals are for grieving. I want the celebrating while I’m alive.

I update my funeral instructions every few years. As I go to more memorial services, I have more information to consider. I want my funeral within three or four days, so that people’s lives aren’t disrupted for weeks, and I want it short. I don’t want a lot of praise or flowery talk about my virtues. Afterward, I want everyone to have pie and coffee. A few days later, I’d like the family to plan an event with great food, dancing, and storytelling. My family will cheer up when they’re embraced by our community of friends. I’d like a green burial, but at present there are no sites in our state.

I intuit that death may not be as big a change as we suppose. Rather, death may be like going home or walking into a new room. I like to think that my relatives and friends will be waiting for me on the other side of the river. I like to think of grassy banks and flower-filled pastures shining in the sun. I like to think a lot of things, but I don’t know them for sure. None of us knows what will happen after death. But we do know we have control over how we live.

Snowfall

All my life I’ve loved snow. As a girl, I played in it—fox and geese, snow angels, snow forts, snowball fights, sledding, and snow ice cream. In the 1950s, snow fell often in the long winters of western Nebraska. I remember one winter when, after the plow came through, mountains of snow as tall as the stores rose in the middle of the streets. We named them the Furnas County Mountain Range and had many adventures climbing and then sliding down them.

As a mother, my favorite days were snow days, when the children and my husband and I could stay home and play board games. I’d make soup and popcorn. I relished taking my children outside to do all the things that I’d done in the snow as a girl. And we’d snuggle in at night and watch movies. I loved falling asleep with my family safe and inside on a blizzardy night, when the streets were impassable and a soft blanket of white peace covered our town.

In those years, I ice-skated and cross-country skied with women friends. We skied on golf courses, in nearby parks, and along creeks in conifer forests. One time, we stirred up an owl who dive-bombed us, leaving us shrieking in joy and alarm. My body warmed up from the exercise, and I was surrounded by beauty above and below. I felt ecstasy on those ski trips.

Now, snow means something different to me. I sit inside and watch it, or occasionally take walks in my snow boots, but in general, I don’t take any risks that could allow me to fall. Snow has become a profoundly spiritual experience.

In Nebraska, the last few years we’ve received less snow. Some winters, we only get a few inches total. All winter long, I yearn for snow, pray for it, and check weather.com for the possibility of a snowflake in the 10-day forecast. When it does snow, I sit by my window and go deep into its purity and softness, its peace and beauty.

Snow falls inside and outside of me. It cools my hot brain and calms my usually agitated body. I hope death feels like watching the snow grow thicker and thicker.

Parts of this article were adapted from the forthcoming book Women Rowing North: Navigating the Developmental Challenges of Aging to be published by Bloomsbury Publishing in January 2019.

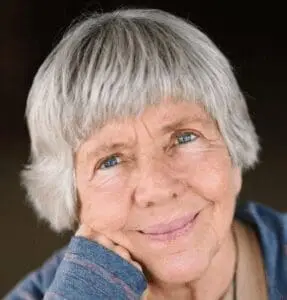

Mary Pipher

Mary Pipher, PhD, is a clinical psychologist, author, and climate activist. She’s a contributing writer for The New York Times and the author of 12 books, including Reviving Ophelia, Women Rowing North, and her latest, A Life in Light. Four of her books have been New York Times bestsellers. She’s received two American Psychological Association Presidential Citation awards, one of which she returned to protest psychologists’ involvement in enhanced interrogations at Guantanamo.