Enjoy the audio preview version of this article—perfect for listening on the go.

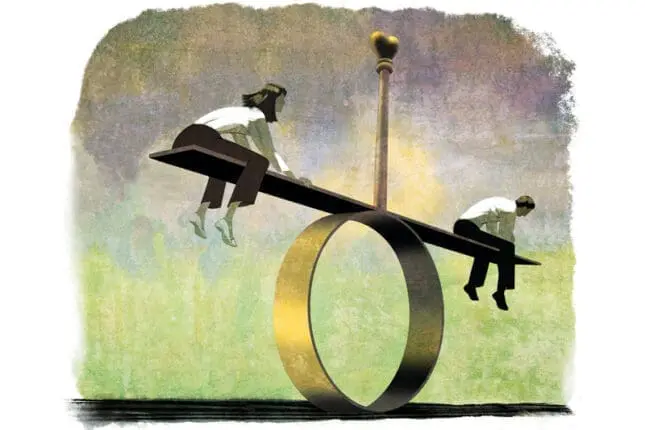

Healthy, equal relationships require compromise, negotiation, and generosity. But when couples don’t have models for mastering these skills, they often regress to old gender scripts as a way to cope. Given how far recent generations have come to free themselves from those scripts, this can feel to today’s couples like its own kind of failure.

In addition to not always achieving a more egalitarian home life, many of today’s couples don’t recognize the cultural pressures that impact their well-being, and they operate as if they’re solely responsible for their struggles—which deepens their sense of failure.

I was raised in Buenos Aires, Argentina, in a patriarchal and family-oriented society, but when I came to the U.S. in the 1980s, I was trained as a feminist couple-and-family therapist to ask gender-centric questions of my clients. I learned from the Women’s Project in Family Therapy, Harriet Lerner, and Monica McGoldrick how to bring feminist insights into clinical practice. When I started my clinical practice, the women I saw were usually reserved, indirect, and sheepish, while the men were loud, demanding, and entitled. My work then was about helping men understand and change power imbalances, and helping women make their voices heard.

For the straight couples I see today, I often end up doing the reverse. There’s been a spike in women chafing at the continued sense of “not enough” in their lives, and straining to reject old gender roles while simultaneously maintaining them. They aren’t going to be the only mother noticeably absent from the PTA meeting just because they’re working 60 hours that week! These women are often at their wit’s end with their male partners, who have a different relationship to today’s pressures and may show up as passive and conflict avoidant.

Feeling more empowered than their mothers or grandmothers likely did, the women are more vulnerable to confusing empowerment with entitlement. They forget, in these times, that their love relationships are still fragile bonds that can’t withstand consistent mistreatment. And in a self-reinforcing cycle, the men, when confronted with their partner’s frustrations, are shutting down, often in a concerted effort not to resemble the angry, demanding, and sexist men of the past.

Most clients I see didn’t grow up with parents who modeled naturally collaborative and egalitarian relationships, nor within a social milieu that was as relentlessly individualistic and consumerist as it is today.

Today’s economic conditions and social expectations encourage both parents to work outside the home, but family practices and social policies aren’t changing fast enough to provide the infrastructure needed for this evolution. In the U.S., we lack access to affordable childcare and rational government policies to help families.

When parents don’t have time to complete tasks each week or lack the money to hire help, they have a time or money famine. And in times of famine, partners tend to blame themselves or each other. What can a therapist do about this new reality, which appears so out of our control?

More than ever, our clients need us to equip them with tools to transition from a hierarchical framework to a collaborative one, which can hold up even as outside expectations press in. This takes time and effort, as it did with my clients Laura and Mike, and it involves looking clearly at how they’re internalizing the pressures of a society that values family less than productivity.

Gender, Culture, and Aggression

In our first session, Laura and Mike faced me from the couch, maintaining a pillow’s width between them, and explained how their decade-long marriage was awash in conflict and frustration. Mike, despite having a confident air about him, seemed ill at ease.

“What are your wife’s main complaints about you?” I asked, wanting to give him the opportunity to speak first.

Clearly startled by my question, he took a moment to compose himself. “I work too much. I’m not emotionally supportive. I disappear into my phone or the TV instead of engaging with her or the kids. And I don’t pull my own weight around the house,” he stated quietly.

Impressed with his gentle delivery, I asked him, “Is she right?”

Before he could answer, Laura jumped in, furious, “He’s completely checked out, doesn’t have a clue about what’s going on, and never follows through with what he says he’s going to do. Meanwhile, I’m running around like a chicken with its head cut off. I have to do it all, and I’m exhausted!”

But she didn’t stop with this list of how little he’s contributing. Pointing a finger in Mike’s face, she screamed, “You’re a nobody, just like your father!”

This vehement attack on his self-esteem caught me off guard. I glanced at Mike, whose head had dropped to his chest. “What do you feel when Laura does what she just did?” I asked.

He stared at the carpet. “I don’t know. Hurt, I guess?”

“Do you ever tell her that?” I asked.

“I’m a guy,” he shrugged. “I can take what she dishes out.”

I paused here as Laura took a sip of water. Like her, many of the women showing up in my office have tried to replace the sense of duty and obligation they noted in previous generations with a fiery sense of individualism, which, though freeing, is making it harder for them to listen to their partner’s experience.

Though many men, like Mike, understand why their female partners are so fiercely independent, they haven’t figured out ways to respond to them when they express their wishes or complaints. And some men don’t believe in the value of sharing their own feelings with their female partners.

To prepare these couples for the work ahead, I often ask three questions: Do you know how to stop a conversation that isn’t going well? Do you have a process for problem solving when you disagree? Do you have weekly or monthly meetings with an agenda where you discuss the division of labor, finances, and what to do on the weekends?

The answers, almost always, are no. Mike and Laura were no different. Almost in unison, they said, “We don’t have time for that!”

I forewarned them that before they’d be able to solve their problems, they’d need to understand how emotional flooding can derail conversations. To this end, I gave them a handout called “What Couples Need to Know about the Brain,” which explains that when the limbic system takes over, the prefrontal cortex isn’t operational.

They were relieved to realize their pattern could be addressed in a handout, meaning they weren’t the only miserable couple out there. Laura folded it neatly and stuck it in her bag as I began to take their histories, hoping we could piece together the factors that may’ve brought them to where they were.

Laura’s mother never worked outside the home and was her primary caretaker. In contrast, Laura is a mother of two and works a demanding full-time job. She’s constantly exhausted, and her guilt about not being able to maintain the same kind of doted-over household that her mother did is off the charts. To counter this guilt, she often demands that Mike do more, but she acknowledges that when he does try to feed, clothe, or entertain the kids, she tells him he’s doing it wrong.

Mike grew up with a single, supportive mother and a distant father. He and his mother had a close relationship when he was young, but like many boys who begin to worry about being shamed by peers for being too close to their mothers, he detached psychologically from her too early. As he’d pulled away, he’d perceived her attempts at connecting with him as intrusive and controlling. By middle school, they’d drifted apart.

When he met Laura in college, they’d had a wonderful romantic period, until the children were born. Now, he thinks Laura is overdoing everything: the planning, the caretaking, and the worrying. At first, he tried to get her to relax, then he started to ignore her complaints because he took them to mean there was something wrong with him, and because ignoring had been his learned way to cope with discomfort in a relationship. After a while, as a response to constant criticism, he stopped trying to help around the house at all. He and Laura hadn’t had sex or touched in years.

Despite feeling demoralized and hopeless, they wanted to stay together. They longed for kindness, compassion, collaboration, and respect from one another. But they hadn’t had what I’ve come to believe is an essential conversation about culture and gender and the way to cocreate the right relationship for them.

“Let’s remember that you’re not alone in getting to this point in your relationship,” I told them. “Most couples stop thinking critically about their relationship after the initial honeymoon stage. They just assume that things will work out. They expect the relationship to be stable and flourish, even though they don’t meet regularly to plan problem-solving strategies, discuss goals, hang out, and try new ways of connecting. Just imagine what would happen if the cocreators of a new startup were to say to each other, ‘Well, now that we got this going, we don’t need to talk about it anymore.”

I could see a flash of recognition and hope flicker across their faces, and they both smiled softly when they rose from the couch to leave the session. As they stepped through the door, I even noticed Laura put a hand on the small of Mike’s back.

Problematic Passivity

In the second session, I turned to Laura first and said, “Let’s start with how you feel right now about your roles as a mother, an employee, and a wife.”

She exhaled. “I’m failing at it all,” she insisted. Then she shook her head and laughed wryly. “I can’t believe I just said that!” She went on to explain that when she was at work, she thought constantly about what she needed to do better at home. And when she was at home, she felt she was neglecting her job.

“When Michael used to ask me for a hug, I wasn’t able to stop thinking of all the things I still had to do,” she said. ”So, I wouldn’t hug him; I’d walk away wondering, Why do I have to take care of him along with everything else? Doesn’t he see how much we’re not getting done? Sometimes I think men don’t feel it the way women do: that sense that you’re never doing enough.”

“Today’s women are under a severe gender-role strain,” I told her. “Many have trouble shaking the belief that it’s their duty to take care of the children and the house, the way their mothers’ did—even if those mothers didn’t work outside the home.”

She nodded, at first slowly, and then more quickly as her face crumpled and tears started to flow. “It’s my job to watch out for the kids’ well-being, right? That’s how it feels,” she began. “Even if everybody says men have this equal role to play now, that’s not what you see at school, do you? It’s still the women at the PTA meetings, the women getting slighted if their kids don’t look okay or do well. He is not subject to that same pressure. He just isn’t!”

Careful not to blame her for these beliefs nor the anger they provoked, I leaned in and told her, “Your feelings are understandable, and the truth of the matter is there aren’t a lot of models for how to create an equitable and collaborative relationship, especially in our me-first culture, which, to be frank, doesn’t always support families. But I’d like to ask you if you can see that how you’re treating Mike reflects how you’re treating yourself.”

I let the silence stand as she absorbed all that we’d shared. Laura then put a hand on the couch cushion between herself and Mike and said, “I don’t always like myself, but maybe I can figure out another way of expressing my disappointment.”

I turned to Mike, who was gazing at his wife with softness. “Now, Mike, tell us how you feel about your own roles as an employee, husband, and father.”

He kept his eyes on Laura for a beat before turning to me. “I mostly feel like I’m failing because of how unhappy she is. Making her happy is important to me.”

I smiled gently and countered with one of my standard questions for passive men who express this intention: “If making her happy is a priority, how come you rarely ask her what she wants or seldom do what she asks?”

Shifting on the couch, he said, “I don’t know. I mean, maybe it’s my response to her anger. I don’t want to come at her when she’s attacking me like one of those Neanderthals that’s always yelling at his wife, so I do things like leave the room instead of getting into it with her. I mean, what if I explode?”

Like many men I see these days, Mike has curbed his outward aggression without completely understanding that checking out and passivity are also cruel. I knew I had to help him deal with his shame and covert anger in a more constructive way.

One thing that’s insufficiently emphasized in our individualistic culture is that we’re responsible for our own well-being and the well-being of our partner, simultaneously. When Laura had an opinion that differed from Mike’s, he interpreted it as a personal affront. And he struggled with it because, as male gender prescriptions go, he wasn’t used to tolerating negative thoughts about himself. When she questioned him or complained, it made him feel bad about himself, he got flooded, and couldn’t stay in the moment.

“Mike, I’d like to see you reconsider the idea that conflict within this relationship is unacceptable,” I said. “When you get passive and withdrawn when Laura’s upset with you, where do you go in your head? I mean, we know you don’t want to engage, but what else are you thinking?”

Mike shifted in his seat and went quiet. I waited for him to be able to meet my gaze, then nodded encouragement. “I think sometimes about leaving her,” he admitted. “I think maybe there’s someone else out there who could be a better fit.”

Laura flinched and retracted her hand, clearly hurt.

“Sometimes, Mike, this idea of choice actually erodes our commitment in relationships,” I told him. “If we’re looking over our partner’s shoulder to see who else is out there when they’re upset with us, there’s that much less energy available to invest in the relationship.”

I paused before adding, “My hope is that in time, you’ll let go of the notion that her concerns are a sign there’s something wrong with her or you. When you see her getting upset, you’ll be able to respond with ‘What can I do to make your evening easier?’ Plus, as you begin to stay engaged and anticipate more of what needs to get done for the family, her exasperation will subside.”

I then praised his honesty and told him that our sessions were a great place to practice revealing more of what he thinks or feels, even if it feels awkward.

“Okay, “I get it,” he said, nodding. “I know I’ve been pretty checked out. I can try.”

Outside Expectations

There aren’t enough hours in a day for isolated nuclear families with two earners to do it all. To help Mike and Laura understand their priorities, I asked them how often they found themselves wanting more things and how hard they worked to get them.

My questions included: How many hours a week do you work? How much money do you make? How many TVs are in the house? When was the last time you got a new car? When you purchased your house a few years ago, did you feel that it was a comfortable level of debt, or do you feel that you’re stretched? Are you better off or worse off financially than your relatives or neighbors?

Mike worked on average 40 hours a week. Laura, about 50. They counted up their material goods and began to wrestle with whether they owned them because they wanted them or because our materialistic culture said they should. It’s not easy for people to realize how closely tied their issues are to their cultural environment, so we dug a little deeper. “What area of your life feels out of control?” I asked. “What gives you the most feeling of pressure? What’s one thing that’d make the day-to-day grind feel easier?”

Laura had a lightbulb moment when she understood how time famine made her feel and how that affected how she thought about Mike. She had a hard time accepting a less than perfect life, and I wondered how hard it’d be to persuade her that she needed to figure out how to do less, not more.

Cocreating a Modern Relationship

In the next session, we started addressing how to problem-solve in a collaborative way. I introduced the concept of weekly meetings where they could use a calendar to divide their labor. They started having state-of-the-relationship meetings, in which they were honest and direct about their differences, disagreements, and disappointments. And I helped them devise problem-solving strategies when they disagreed.

Whenever their shame and insecurities got activated, we’d pause and backtrack to clear more gender and cultural brush. What assumptions about relationships were getting in the way? What gender-role strain was being expressed in these dilemmas? What cultural mandates were they attempting to uphold?

In time, they became more hopeful about their ability to evolve toward more gender balance and collaboration. Laura became less angry; Mike became less afraid of disappointing her.

I’m pleased but also aware of how challenging it was for me as a therapist to help them. Though Laura and Mike’s struggles aren’t unique these days, I sometimes found myself dysregulated by their gender-based conflicts. It was easy to lose patience with their behavior and occasional myopia when it came to their cultural environment. Still, I realize that when we therapists can act like the egalitarian parent such clients may never have had, we can maintain integrity and steer them in the right direction.

Case Commentary

By Alicia Muñoz

Sara Schwarzbaum’s attunement to the high-conflict, gender-role-challenged couple in this case study is informed, nuanced, and compassionate. She frames them as partners in a relationship and as individuals influenced by their own family-of-origin conditioning, all without losing sight of the societal context in which outdated gender-role expectations have been confusing and derailing many modern cis-gendered, heterosexual partners trying to redefine what healthy partnership looks like.

She also notes how each partner’s personal choices—even when they seem right for the individual—have a relational cost. As freeing as Laura’s fiery independence might be for her, it desensitizes her to her husband’s emotional pain. Similarly, when Mike submerges his anger toward Laura so as not to resemble the stereotypical toxic angry male, it further erodes their connection. He nurses passive-aggressive escape fantasies that foreclose the opportunity for a difficult but honest conversation about his true feelings, boundaries, and needs.

Schwarzbaum navigates these complexities masterfully. She’s sensitive to the hypocrisy of social expectations pressuring both partners to work even as family and woman-hostile policies make meeting this and other expectations unsustainable, especially for lower- and middle-income couples and families. Schwarzbaum brings a calm, wholistic perspective to these overlapping paradoxes: she operates as a kind of relational tuning fork for her clients, helping Mike and Laura get clearer about where they’re out of sync with themselves and each other.

There was one moment with this couple I might’ve approached differently. When Laura screams, “You’re nobody, just like your father!” I would’ve been wary of colluding with her overtly shaming attack on his character. I’d want to let Laura (and Mike) know ASAP that getting up in your partner’s face and yelling that they’re “a nobody” while dragging one of their parents through the mud is not business as usual, even in therapy—or especially in therapy.

Rather than questioning Mike about Laura’s comment, as Schwarzbaum did, I would’ve asked Laura herself about it, saying something like, “Are you aware of what you just did?” If my question didn’t snap her out of her reactive trance, I might’ve gently but firmly recapped what I’d witnessed: “I asked Mike a question. You answered for him. Then, you went for the jugular by demeaning him and his father. Would you be willing to take a breath and get curious about what feelings might be under the surface here?”

With a couple like this, I also think there’s a risk of spending too much time cognizing, intellectualizing, and problem solving—all therapeutic interventions I will readily admit I personally rely on far too often. I’m reminded of the quote by the German psychiatrist Frieda Fromm-Reichmann, “The patient needs an experience, not an explanation.” Even when couples find handouts on the limbic system helpful, focus on the three important questions Schwarzbaum asks at the start of the session, or engage in weekly meetings on task delegation, a vast majority of them—including gender-role challenged couples like Laura and Mike—need the most help with experiencing and sharing vulnerable, shameful, scary parts of themselves they’ve hidden.

Schwarzbaum does much of this work when she guides Mike and Laura to recognize and identify their go-to intimacy avoidance strategies, like busyness. In the past, gender-role expectations were—among other things—a way of creating predictability, denying complexity, and reducing anxiety. Postmodern gender-role dynamics may have a similar function. On the other side of all façades, defenses, roles, and presentations, a powerful wave of freeing, experiential work begins.

Sara Schwarzbaum

Sara Schwarzbaum, EdD, LMFT, LCPC, is founder of The Academy for Couples Therapists, an online training program, and of Couples Counseling Associates in Chicago, where she currently practices. Her numerous publications include “One Size Does Not Fit All in Couple Therapy: The Case for Theory Integration.” Email her here.

Alicia Muñoz

Alicia Muñoz, LPC, is a certified couples therapist, and author of several books, including “Stop Overthinking Your Relationship” and “A Year of Us.” Over the past 18 years, she’s provided individual, group, and couples therapy in clinical settings, including Bellevue Hospital in New York, NY. Muñoz currently works as a senior writer at Psychotherapy Networker. Her latest book is “Happy Family: Transform Your Time Together in 15 Minutes a Day.“