As each of us grows older, we can try to embrace the full possibilities of aging, even alongside its challenges. That’s a genuine gift for our clients as well as the important people in our personal lives, regardless of their age. And, lest we forget, it’s a gift we can give ourselves.

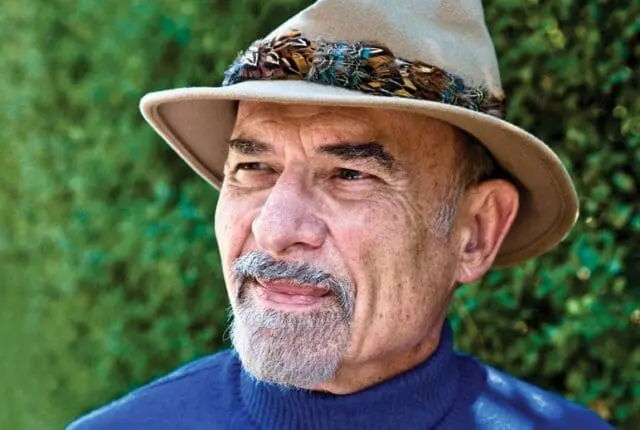

In the following interview, iconic existential psychotherapist Irvin Yalom, age 86 and author of the seminal book Staring into the Sun: Overcoming the Terror of Death, traces how his quality of presence with clients has changed over time.

PSYCHOTHERAPY NETWORKER: When you look back over all the years you’ve been practicing, what’s the biggest difference about your approach today from when you began 60 years ago?

YALOM: What stands out most is that I’m so much more at ease with my own person, much more self-disclosing, and much more direct in how I connect with patients. For example, I recently saw a young woman who’s had polio since she was a child. I felt a lot of admiration for how she’d handled her illness and the courage with which she’d conducted her life. So I expressed that to her in a very immediate way. In my earlier years as a therapist, I probably wouldn’t have felt the freedom to express my personal reaction so directly.

These days, I try not to censor myself or rigidly follow any particular kinds of rules. I find myself just being much more human and present and open with the people I see. I’m also more comfortable than ever going directly into the here-and-now experience. I don’t let a session go by without checking in with a patient about how the two of us are doing in that given session—if we’re somehow off or perhaps experiencing a special moment of closeness.

PN: You clearly feel more comfortable with yourself at this stage in your career, but are there any ways you feel more challenged because you’re an older therapist?

YALOM: That’s really hard to answer because I’m in the unusual position of being very selective in choosing the patients I see. After all these years, I have a nose for the people who I think I can do work well with, and a nose for those who I can’t. So I’m not seeing the challenging borderline patients that I would in the past. I can spot right away what’s going on, and I can say directly, “These days I’m only doing very brief therapy and I think you’re going to need someone whom you might need to see over a longer period of time.”

PN: Are there ways in which being an older therapist has enhanced the quality of your work?

YALOM: More than ever, when somebody comes to see me in therapy, even for a single session, I have a sense of wanting to be generous, of wanting to offer that person something of deep value. I’m even more aware at this point of how being a therapist puts me in a privileged position of having access to the intimate lives of other people in ways that few people are permitted to experience. Over the years, I find myself valuing it more and more.

PN: Is there something about being a psychotherapist that you find personally helpful as you face challenges in your own life around aging?

YALOM: As most people age, they find themselves losing friends and family who are deeply important to them, and feeling more isolated. But part of the advantages of being a therapist is not feeling so isolated as you age. You can continue to be taken into the inner worlds of people and share so much of their experience of life. Being a therapist offers a doorway through which I experience intimate moments with people of all ages.

PN: You’ve written so much in your career about facing mortality and life’s existential issues. Do you often feel a special quality of connection with people who are dealing with end-of-life issues?

YALOM: I’ve had a lot of experience working with people facing terminal illness and nearing the end of their lives. For 10 years, I worked primarily with people who were dying of cancer, many of whom were old and isolated. Often people don’t know what to say to them, so they’re cut off. Also, they don’t want to drag everyone down with their fears and despair. I’ve learned how helpful for them it can be for me just to break through that, and to be intimate with them. I let them know that I feel comfortable with talking about death and facing the end of life.

Years ago, I remember being quite struck by watching Elisabeth Kübler-Ross interview some very sick, dying patients, and opening the interviews by asking them directly, “How sick are you?” That way of going into the interview with them said in effect, I’m willing to go wherever you’re willing to go. You don’t need to hold anything back from me. I’ll go deep with you.

PN: What have you learned about the biggest challenge people face as they try to deal with their own dying?

YALOM: I don’t know that people have a fear of death as much as they fear dying. It’s the process they dread. Of course, many people who are religious believe in an afterlife, and for them, there’s not so much terror. But for most people, the biggest fear about the dying process is their loss of control and the loss of their own autonomy—the fear they won’t be able to move or will be physically isolated. Many, perhaps especially men, fear the loss of their sexual powers. But maybe that’s really about the loss of youth. For many people, the sexual thrust is what gives them the feeling of power and vitality. Seeing that fade away can be deeply demoralizing.

PN: You’re not only a prolific writer, but also an avid reader. Is there something that’s been written about the experience of dying that’s especially affected you?

YALOM: The one book that stands out is Tolstoy’s The Death of Ivan Ilyich. One of things that makes that novel so powerful is the main character’s recognition that perhaps he’s dying so badly because he’s lived so badly, and that there may be a chance to change that right up into the moment of death.

As he begins to change the way he is in the world, especially with the young man who’s his caretaker, he comes to realize that he can live differently and live better, even to the moment of death. It’s hard to think of a more important insight that therapists can pass along to their patients who may be facing their own mortality.

PN: After all these years of being a therapist, what’s a bit of advice you might offer our field about how we as a profession might enrich the practice of therapy?

YALOM: Well, I’m afraid that I’m going to have to defer to Carl Rogers on that. As he always said, the important thing about psychotherapy is the relationship and the empathy, the genuineness, and the unconditional positive regard that the therapist brings to it. These days people talk a lot about empirically validated therapy, but there’s nothing that’s more empirically validated than Rogers’s assumptions about the therapeutic relationship.

Irvin Yalom

Irvin Yalom, PhD, is an emeritus professor of psychiatry at Stanford University and the author many books, including Becoming Myself: A Psychiatrist’s Memoir.