I’ve always made it my primary goal to save the marriage, if at all possible; however, I’ve often felt that I was working harder at it than either of the partners involved, especially with the couples who come to my office only to check off an imaginary box—“tried couples therapy”—before heading off to consult their respective lawyers. Of course, even among these last-ditch efforts, some unhappy couples do find new and better ways of relating to each other during therapy and decide to stick together. But what I’ve come to realize is that once a marriage has sufficiently unraveled, therapy often hits an impasse, and divorce becomes an inevitable reality.

At one time in my career, I’d have considered divorce as an outcome of therapy to be a failure—by the couple and by me. But over the years, I’ve learned to think of it as another opportunity to help. I’ve come to realize that I can support divorcing couples by helping them explore viable alternatives to the often wounding and adversarial legal process that normally ends marriages—a process that can make what’s already a bad situation for the couple, their children, and their extended families incalculably worse. I’ve learned that I can help couples end their union in as thoughtful and pragmatic a way as possible. In other words, both partners can come through the experience with their dignity intact, their sanity whole, and in a greater spirit of cooperation and goodwill—attributes they’ll need as they continue to share responsibilities for their investments, their interests and their children.

Thus, when couples clearly intend to divorce, I often guide them through what I call an intentional divorce, which I reframe as not the end but the completion of their marriage. The framework I’ve developed for the intentional divorce comprises three phases. The first is the crisis phase, when both partners have concluded that they’re heading for divorce, and the reality and finality of their decision triggers a state of shock, disbelief, and devastation. Even though each partner may have known divorce was coming, acknowledging it in therapy often provokes intense emotional upheaval. Managing this psychological disequilibrium in sessions is one of my clinical priorities.

Once the couple has begun to calm down and show signs that they can live with this huge, new decision in their lives, I begin a more strictly practical course of educating them on the legal and lifestyle choices that can make the process of divorce healthier and less traumatic. This educational part of the crisis phase helps the couple handle the overwhelming, myriad choices in front of them without sending them back to an emotionally reactive state, in which decision making is impossible.

Next comes the insight phase, when the partners do the deeper work of letting go of the marriage and their own identities as spouses, and begin moving into their new roles as single people, who are still coparents and possibly even friends. Afterward, with my help, they embark on the vision phase by completing their relationship with a ritual or a goodbye that helps them move forward in their post-divorce lives.

The Crisis Phase

I recently worked with Pam and John, a couple who were both stockbrokers and parents of young children. Pam had given up her job to stay home with both kids after they’d moved from the city to the suburbs. At some point, she began cheating on her husband. Although she ended the affair when he found out, and they sought me out ostensibly to help them heal their relationship, it became clear after eight or nine sessions that Pam didn’t really want to restore the marriage: she wanted out. In fact, she’d begun the affair because, in her mind, the marriage was already over.

As she put it to me in an individual session at the beginning of our couples therapy process, “I was committed to the marriage for years, but John was never home. We never made love, and he never called me. He was at work all the time. I felt like he didn’t really want to be with me. In fact, he rented an apartment in the city where he slept five nights a week. He never even answered my texts! When he was home, the kids barely knew how to deal with him. He was a stranger to us.” Pam said she’d asked him if he was having an affair, and he’d sworn that he wasn’t. “Maybe his mistress was the stock market. I don’t know,” she said. “But I tried for years to get him to come to therapy. He refused, saying he didn’t have time.”

In the couples therapy, we worked to help Pam determine whether or not she’d been having the affair to get John to notice her again. But it turned out, her affair was what I call a can opener—a way to get out of the marriage and end things, a message to her husband that she was done with the current arrangement. What seemed unfair to John was that she hadn’t told him first. Now he was just catching up, easing into the realization that the relationship was ending and Pam had known this for some time.

This common circumstance, with one partner way ahead of the other in the decision to divorce, can confuse therapists, who, seeing hope for reconciliation in this divergence, may align with the more reluctant partner. Yet in my experience, the reluctant partner not only catches up relatively quickly, but often admits to having known on some level that the marriage was over. John, for example, said, “The moment I signed a lease for that apartment in the city, I think I realized in some way that the marriage was over. I should have owned up to it myself and definitely should have been more direct with Pam.”

After several sessions of processing the anger and betrayal that they both felt—her for being abandoned and him for feeling blindsided by her affair—they agreed that the marriage was, indeed, over. In fact, John announced in one session that he thought he might be gay and wanted to explore his feelings for men, something he’d never done.

It was important at this point in the treatment to use strong dialogue work to help Pam and John empathize with each another. So I had John talk to Pam about his fears and anger at her; she then talked to him about her resentment that he’d never been honest with her about his sexual interests. To help them learn to share their feelings in a way that decreased reactivity, I had John imagine he was Pam and asked him to try and feel in his body what it felt like to be her in this situation. Did he have any sensations in his shoulders, his neck, his chest, his stomach? He said, “Yes, I feel tight in my stomach, like I have to throw up, actually.” When I asked him to elaborate, he continued, “If I was Pam, I’d be so angry, I’d be sick inside, and below that I’d probably be afraid about my kids and my future. Maybe I’m trying to stuff all my anger inside and that’s why I’m feeling so sick.”

I then asked Pam to put herself in John’s universe, describing what she felt in her body. She said, “I feel like I can’t breathe. My throat is closed. I imagine that John feels like he’s running, running and can’t get any air.”

“John, is that true?” I asked.

“Well, yes, I guess so,” he replied. “I’ve been running my whole life—from myself, from the truth. I’m so tired of running. I just can’t do it anymore.”

Afterward, I took them through a process where they each shared “what I wished I could’ve said to you,” and spent some time on regrets—which led to the most honest conversation they’d ever experienced. When Pam told John that the attention she got from her affair partner was what initially attracted her, I asked John to see if he could find a place where he could feel empathy for her experience. Putting aside his defensiveness, he finally acknowledged how absent he’d been. As he got beyond his hurt and anger, he began to recognize that there were two different narratives of the relationship, and how, as a result of his disengagement, he’d contributed to Pam’s decision to distance herself from the marriage.

Eventually, Pam admitted that she’d always suspected John’s feelings for men but had avoided confronting him about it. With some help, she said she could identify with how difficult it must be for him to drop this big news about his homosexual feelings in the session. After they explored their hurts and disappointments together, they were ready to grieve the vision they’d each held of the marriage when they first got together. This is the point at which couples finally let go of their lingering hope for reconciliation, and it becomes clear that their marriage is ending for good.

Typically, once the couple has made the decision to divorce and after I’ve explored all available alternative options with them, I wait to see if they’ve become stable enough emotionally to begin thinking in terms of practically and reasonably ending the marriage in a peaceful way. Sometimes couples need a few weeks off to go home and discuss the possibilities. Sometimes they take time alone to talk with friends or an individual therapist. I ask them to commit to another session a few weeks out, and reassure them that no matter what they decide, I can still be with them throughout the process, to guide and support them. If they have questions, they can email or call me.

If couples contact me again, I ask them specifically to commit to a conscious, intentional divorce, during which they slow down the process. Instead of making impulsive decisions, they commit to working through each detail of the divorce, either in sessions with me or with a mediator or a collaborative divorce attorney, someone professionally and ethically bound to neutrality between them, who helps them negotiate their separation fairly.

At this point, even though I consider us still in the crisis phase—the decision to divorce is too new for them to be fully comfortable with it—my role begins to shift from therapist to coach. I educate them about their options for advocates and advisors and tell them about community resources for nonadversarial divorce teams. In fact, collaborative attorneys, mediators, and divorce coaches in most towns or urban areas will work with therapists as a team to provide advice, support, and legal assistance. As a therapist, I benefit from having a list of these support people ready, having already met with them and found out how they operate, what they charge, and how they feel about a more conscious divorce process.

At this point, with emotions still high, each partner may be vulnerable to the well-meaning ministrations of family members and friends, who recommend “tough” attorneys, able to “protect” each spouse from the other. Sometimes divorce attorneys will ramp up tension and anxiety in spouses by reminding them of all the dire potential risks and hazards they face from the “other side,” and requiring, “just in case,” large retainers of many thousands of dollars. This kind of advice doesn’t usually encourage a spirit of calm reason and compromise.

A mediator, however, can be an attorney or a trained therapist, counselor, or financial advisor, who doesn’t represent either side and can meet with both partners at the same time to help them work through a parenting plan, a financial agreement, and any details that need to be settled before going to court. Some of the work that goes into the plan can be done in therapy sessions, particularly if there’s high conflict around certain triggering issues.

In Pam and John’s case, both of them worried about custody arrangements, each afraid the other would fight to deny time with the children. John, in particular, was afraid this would happen if, after they separated, he began a relationship with a man. So therapy became a safe container, where they could talk about their fears and work through some of the more frightening aspects of their potential future as coparents. While creating a concrete parenting plan that seemed fair to both of them, we allowed time to talk about the problems and emotions that got triggered in the process. We had to work through John’s travel schedule for work and, taking out both their calendars for the next year, decide how they’d handle visitation with the kids. This enabled them to go into the mediator’s office with a clearly laid-out parenting plan.

Another possibility I suggest to couples at this point is a collaborative divorce, in which each partner hires a separate collaborative divorce attorney. These attorneys commit to a nonadversarial divorce without escalating their fees or fighting in court, and all parties agree to this in writing with a focus is on dispute resolution instead of “winning.”

The Insight Phase

Connecticut, where I practice, mandates a three-month waiting or cooling-off period for divorcing couples from the time the paperwork is filed to the court date. We use this time in the couple’s therapy to work through the insight phase.

During this phase, the couple reviews the marriage, exploring what brought them together, what they’ve learned from being married, how they’ve helped and hurt one another, and how they’ve come to realize that the marriage can’t continue. Although couples can still be triggered and go back into the disbelief and irrational rage of the crisis phase, this phase primarily involves processing sadness and learning about the role each person played in bringing the marriage to its completion—which is important in preparing each partner to avoid repeating the same mistakes in later relationships.

Because the grief around the death of the marriage is now palpable, replacing the raw shock of the crisis phase, the couple may be overcome with a sense of loss. Even if the partners aren’t mourning the loss of their spouse per se, they’re likely mourning the loss of the promise of what the marriage was supposed to be. Perhaps, for instance, it’s the dream of a retirement house in Maine, on the coast, with their grandchildren at their feet. Or maybe they thought they’d travel together when the kids grew up. Neither of them dreamed about a future that included divorce, splitting up their property, and discussions about sharing custody.

In this phase, I see my role as twofold: I’m holding the grief with the couple while helping them create a vision of something new as they move into their future. I may see each partner individually for one or two sessions at this point, asking permission first from each partner to keep the sessions private and not to use disclosures in the sessions in court. I include the caveat that no legal aspect of the divorce will be discussed in these individual sessions and ask each to sign releases to that effect.

Often, because these issues are clearly on their minds at this stage of a divorce process, I ask people to list anything that they blame their partner for, and then we move to zeroing in on the ways that they’re feeling self-blame. Pam, for instance, listed her guilt about the affair and her regret that she didn’t try to work on their sex life before seeking out another man. John listed his guilt about his gay fantasies and marrying Pam before he’d explored his own sexual fluidity. Both worked on their lists in individual sessions, but they shared them in a highly structured joint session, in which one partner talked about what seemed most important on his or her list while the other simply mirrored and thanked the partner for sharing. If things got reactive, we slowed down the process and talked about what was being triggered. The goal was to go from blame and shame to empathy and then letting go.

Many times, bringing in a sense of appreciation for the positive aspects of the marriage is crucial at this point, but it’s also difficult, as it can create complicated emotions. It’s often easier for people to tell themselves that the marriage was always a failure in order to make the divorce hurt less. Still, cultivating appreciation helps with the healing process for the whole family. If they find it challenging to come up with anything positive, I might ask the partners to list what they appreciate about each other as parents. If the couple had good years together, I might ask them to recall the best years of their marriage. Throughout, I hold the vision for them of a better life and a new phase of their partnership, one of reduced conflict and perhaps healthy coparenting.

I introduce them to the idea of an appreciation dialogue—a series of four or five sentence stems that I print out for both partners as a way to honor one another and the positive aspects of the marriage. I usually guide the couple in completing the stems in session, but encourage them to try the process at home if they’re working well together on their own. For example, I began by offering the following sentence stem to Pam: “One thing I appreciated about our marriage was .?.?.?,” which she completed by saying, “that you were always a good provider for me and the kids.” I asked John to mirror back what she said, to encourage his active listening, and then to respond to the same stem. He said, “So you appreciated that I was always a good provider and you appreciated the lifestyle I gave you and the kids.” Then he added, “One thing I appreciated about our marriage was the way that being married to you helped me grow up as a man.” Pam had an emotional reaction to this and wanted to respond, but I asked her to just hold the space by mirroring. She didn’t need to defend, explain, or apologize. She only needed to listen, even if she felt reactive.

The next sentence stem was harder: “One dream I’m letting go of is .?.?.?.” To this, John added, “the dream we had of the beach house we were going to buy one day. I’m sorry we never made that happen.” After Pam mirrored back his statement, I encouraged John to explore his role in preventing the dream from coming true. “I focused too much on my life in the city and not enough on the dreams we talked about in the beginning of our marriage,” he said. “That was a mistake.”

Other sentence stems include “One thing I’m deeply sorry for is .?.?.?,” “One way I’ll always care for you is .?.?.?,” and “I’m helping you move forward by .?.?.?.” During this process, each partner may cry or get defensive. To keep the discussion from deteriorating into a fight, both sides must hold the mirroring process to create a space of mutual respect.

When Pam and John were deep into their dialogue, Pam broke down in tears and was unable to catch her breath. It was clear that John was unable to figure out what to do in that moment. In the past, he’d have held her; now he was learning a new, more distant role, and he didn’t know how he should comfort her. I asked him to ask Pam, “Do you want me to hold your hand right now?” Pam said, “OK,” and he reached out and held her hand. If they’d wanted to hug, they could’ve done so, but it’s important that they decide themselves if they’re going to move into that type of physical contact.

During this point in the work, some couples decide that they’re now ambivalent about divorcing. If one partner feels deep regret, the couple may revert to the crisis phase, and the divorce may be temporarily put on hold. Although I’ve never had a case where the couple reconciled, it makes sense that the possibility would arise during this phase of the treatment. Indeed, the potential for all outcomes is possible, and I don’t direct or guide the couple in any one direction. Instead, I wait to see what happens in the weeks following the appreciation dialogue sessions. Most couples come back with a renewed sense of purpose about the divorce, but find they have less resentment and more goodwill toward their partner as a result of the work. The letting go of the marriage can now be done with less guilt, and it begins to feel like the marriage is coming to its completion.

The Vision Phase

Divorce can bring up intense feeling of shame, but it can also be a time of hope and potential transformation. In this final vision phase, the couple creates, with my help, a new agreement to move forward, relinquishing their explicitly monogamous marital relationship with each other in favor of a new one, as coparents and friends, or sometimes agreeing to detach completely from one another. I remind the couples that staying angry with each other keeps them locked into the worst version of their marriage. A ritual can be crucial to honoring the marriage while helping couples let it go, transmuting the divorce from a shameful experience of failure to an important life passage, with its own dignity and place in their lives, however painful the process may be.

One example of a divorce ritual was made famous by the celebrity couple actor Gwyneth Paltrow and musician Chris Martin, who asked a Kabbalah rabbi to officiate at their uncoupling ceremony, during which they threw rocks into the ocean to represent their wandering spirits. The words they used were “Blessed are you in coming in, and blessed are you in going out.” It’s easy to ridicule such hippy goings-on—as the popular media did—but, in fact, rituals of this kind can be both comforting and therapeutic.

Even if the spouses can’t manage to forgive each other, they may do a ritual separately to let go of things they want to release from the marriage. One lesbian couple, Jude and Franka, went separately into their backyard when the other was out of the house, prior to moving into separate homes, and burned in a small outdoor fire pit something that represented the resentment that they were holding onto. Jude told me she wasn’t ready to move into her new life while holding onto the anger and resentment she was feeling about Franka’s affair. So she took a photo of the two of them from their wedding that reminded her of what they no longer were, and she let it burn. “As I watched the smoke rise up into the air, I felt myself get lighter,” she said. “I pictured myself letting go of some of the anger I’ve been carrying around. I said a prayer for her, for Franka, for her future. I didn’t want to do the burning ritual with her. I couldn’t. But I had to let go of some of the intense feelings that were in me before I could move on.”Franka told me she’d burned a pile of paid bills in the fire. “Jude and I had racked up an amazing pile of debt. And when we sat down in the mediator’s office, we realized that a lot of it was Jude’s bills for her excess spending and crazy lifestyle. I burned this giant stack of paid bills and visualized letting go of this debt, this debt to Jude, like I no longer owed her anything. I don’t have to pay off her credit cards, I don’t have to fix her, and I can move forward in my own life. She was a good wife, but I have to go live my new life now. When I saw those bills go up in flames, I felt free.”

Bill and Geri, another couple, spent their first sessions with me calculating in gruesome detail the tens of thousands of dollars they’d spent on their wedding—the clothes, the catering, the band, the liquor, the photographer, the cinematographer—and fighting over who’d paid how much and whether the marriage itself had even come close to being worth the wedding. (They both agreed it had not.) Once they’d recognized the investment they’d made in beginning their marriage, I helped them realize that since there wasn’t any officially recognized ceremony or ritual that would give equivalent weight, meaning, and dignity to ending their marriage, they needed to come up with one themselves. So in this final vision phase of therapy, we decided to create something more meaningful than just spending money on a goodbye party. They each wrote a letter to the other, stating 10 things that the marriage had meant to them.

On his list, Bill wrote, “Being married to you in the early days made me feel safe and loved, and it changed my life having known you.” Geri wrote, “I liked how close we were when we traveled and you introduced me to new places, and it meant a lot to me that your parents welcomed me into your family.” When each of them had completed 10 aspects of their marriage they’d found meaningful, we created a ritual for ending the marriage. They invited a few close friends for a simple ceremony at an outdoor spot near a large tree, where they’d first met. There, they each read their letters aloud, walked slowly in a circle around a tree in opposite directions—a ritual similar to walking down an aisle, but this time they were walking away from each other. When they met again, having circled the tree, they each gave the other a deep bow of recognition. For both, it was a simple, quiet, and meaningful moment of mutual acknowledgement.

Most divorces end in a courtroom with a short legal decision read from the bench, a gavel dropped, and a feeling of anticlimax. There’s often a feeling of awkwardness immediately afterward, as both now ex-spouses stand uncertainly outside the courtroom, unsure of what to do next. “See ya around” doesn’t quite capture the importance of the moment. Creating a ritual in this intentional divorce phase helps bring the marriage to a more emotionally resonant ending, symbolically marking the beginning of a new stage of life and implicitly giving people permission to move on.

At this point in the treatment, I review the process with the divorcing couple and see if anything needs more work or detailed explanation. One or both partners may continue in individual therapy with me or with a referral. Many people are left with the need to create a vision for their life and a new experience going forward. Individual therapy includes helping them adjust to single life, single parenting, and eventually dating again. But it’s always important throughout the process of divorce counseling to remember that while we’re helping the couple end one period of their lives—virtually always involving pain and loss—we’re also helping them begin a new one.

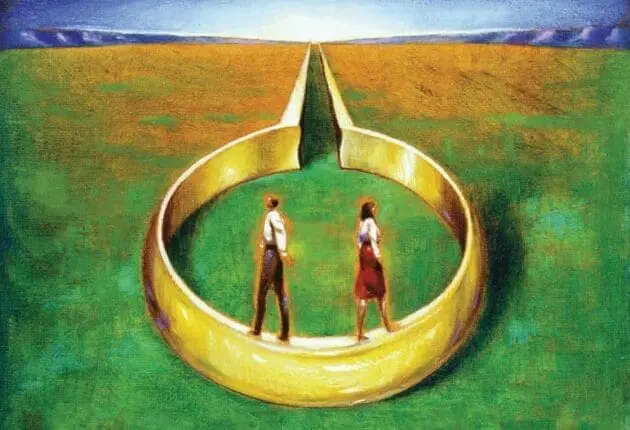

Illustration © Paul Anderson

Tammy Nelson

Tammy Nelson, PhD, is an internationally acclaimed psychotherapist, Board Certified Sexologist, Certified Sex Therapist and Certified Imago Relationship Therapist. She has been a therapist for 35 years and is the executive director of the Integrative Sex Therapy Institute. She started the institute to develop courses for psychotherapists as the need grew for certified, integrated postgraduate sex and couple’s therapists in a growing field of mental health consumers who need more complex interventions for their relationship needs. On her podcast The Trouble with Sex, she talks with experts about hot topics and answers her listeners’ most forbidden questions about relationships. Dr. Tammy is a TEDx speaker, Psychotherapy Networker Symposium speaker and the author of several books, including Open Monogamy: A Guide to Co-Creating Your Ideal Relationship Agreement (Sounds True, 2022), Getting the Sex You Want: Shed Your Inhibitions and Reach New Heights of Passion Together (Quiver, 2008), the best-selling The New Monogamy: Redefining Your Relationship After Infidelity (New Harbinger, 2013), When You’re the One Who Cheats: Ten Things You Need to Know (RL Publishing Corp., 2019), and Integrative Sex and Couples Therapy (PESI, 2020). Learn more about her at www.drtammynelson.com.