As a kid, I loved the smell of pizza but couldn’t allow myself to eat it. If you’d asked me to explain why, I would’ve said I didn’t like pizza. But the truth was, pizza looked delicious. It was just forbidden—not by my parents, but by some universal law that decreed I personally did not eat pizza. I couldn’t tell you where the law came from, only that it was absolute. On Tuesdays, my school’s all-purpose gym would fill with the smell of hot tomato sauce and melted cheese, cardboard boxes piled high. If your parents paid two dollars, you could get two slices for lunch. My parents offered over and over to give me the money, but I always said no. I could no more reach out and accept a slice of pizza than I could force my body to run into traffic.

Thirty years later, I was scouring the internet to learn from Autistic adults how to better support my Autistic son. One evening, after taking him to his occupational therapist (and enjoying the therapy swings and fidget toys more than he did), I opened my laptop and came across a list of traits common in high-masking Autistic women. My jaw dropped. There I was, on the screen: All-consuming passions. Feeling alien among humans. Overwhelming empathy. Social anxiety. Sensory sensitivities. The list wasn’t diagnostic, but I had 160 out of 180 traits. In fact, the more I learned about autism as difference or disability in the areas of social relationships, language and communication, sensory processing, and attention, the more autism explained just about everything about me. I celebrated my self-diagnosis and received a clinical diagnosis nine months later.

My first year in the Autistic community did more for my mental health than 20 years of therapy had, combined. But autism alone didn’t explain the rule about pizza—because it wasn’t just pizza. I had behavior that was unusually rigid, even for an Autistic person.

As a child, I only wore skirts—even if I wanted to wear pants. At age six, cognitively precocious, I refused my parents’ pleas to get fully out of diapers, terrified not of the toilet but of giving up the power-struggle. I took the lead in every game with peers—or couldn’t play. Kids called me bossy. Adults worried I was inflexible and purist. But I couldn’t help it. In fact, the harder an adult pushed me to “be flexible,” the more entrenched I felt. A true loss of control could trigger a full-blown panic response, which I tried and sometimes failed to avoid. Once, at a family friend’s house for dinner, I sipped some (delicious) soup without asking about ingredients. When the hosts told me it was beef broth (I was a strict vegetarian), my body leapt from my chair as though stung, and my vision tunneled. I stumbled to the bathroom and knelt over the toilet, gagging and almost passing out.

When our son was four, my husband and I noticed that the sensory accommodations his OT recommended were not helping as much as we’d hoped. Our son loved the hugs, popsicles, and rhythmic singing we offered throughout his day, but he still went from calm to screaming at small triggers that had nothing to do with sensory distress or loss of routine. A misplaced crayon stroke could cause a 45-minute meltdown. Trying to wash his hands after school was a physical battle, even though he loved playing in the sink. We always got the same advice: Stay calm, meet his sensory needs, hold your boundaries, and the meltdowns will decrease.

But they didn’t.

The worst was bedtime. Each step in the routine of toothbrush, pull-up, and PJs would trigger manic dysregulation. Nothing helped. Not a visual schedule. Not singing through the steps. Not raising my voice. An early childhood specialist told me I should give three warnings, then leave the room until he was calm. I dutifully followed her advice, but all my leaving did was send my child into a panicked rage.

There had to be a better way.

When a neighbor mentioned Pathological Demand Avoidance (PDA) to me, the pieces fell into place—not only for my son, but for myself.

First described in the 1980s, PDA has gained awareness in recent years likely due to social media and an overall increase in understanding of neurodivergence. Research is ongoing, and PDA is not (yet!) in the DSM. Like many PDA advocates, I believe PDAers have hypervigilant autonomic nervous systems that flip into “survival brain” responses when faced with a lack of autonomy, control, social equality, or sources of external regulation. This threat response leads to “demand avoidance.” Many PDAers are Autistic and/or ADHD and benefit from neurodivergent-affirming strategies like special interests, sensory accommodations, and working with monotropic attention. There is an open debate in the community about the relationship between PDA and autism.

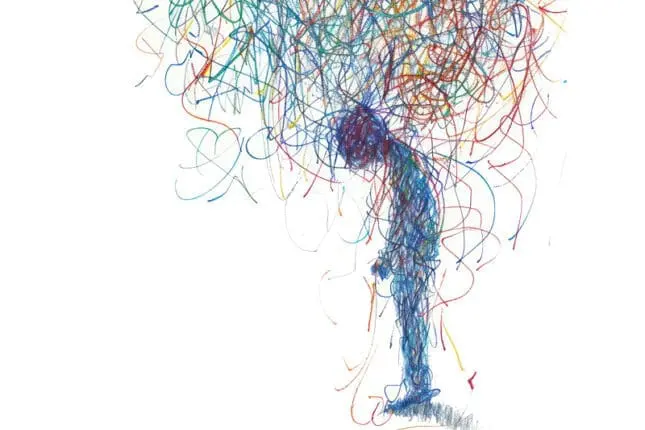

I have a hunch that PDA is not as disabling in cultures where children are granted more autonomy by default in the context of the proverbial Village. But in the West, PDAers of all ages are struggling in droves. Our threat response can impact our ability to meet basic needs like eating, toileting, sleeping, hygiene, connecting with loved ones, and staying safe. We can get triggered by both external demands (the demands of school or work) or internal demands (the sensation of hunger or needing the bathroom), and we can express our threat response in externally obvious ways (fight, flight) or more internal ways that are easy for others to miss (freeze, flop, fawn).

The PDA community is noticing other common traits. PDAers are often socially outgoing and missed for autism diagnosis among clinicians trained in Autistic stereotypes. We tend to be strong autodidacts who are charismatic, creative, and empathic when we feel regulated and safe. We often mask our threat response in places where it isn’t safe to let it out, and then fall apart later. We can have a wide range of support needs, just like the Autistic population. And we are vulnerable to debilitating burnouts.

The key to supporting PDAers is understanding that what looks like defiant, oppositional, or rigid behavior doesn’t stem from a character flaw, or “bad” or “permissive” parenting, but from an overactive autonomic threat response that requires specific accommodations to help us stay regulated. Given our particular triggers, behaviorist interventions (like “three warnings and then Mama leaves the room”) further activate the threat response and our accumulated stress. Essentially, you can’t argue with the autonomic nervous system.

I found out about PDA from a neighbor of color, but the overall roll-out of PDA as a framework has been highly unequal across race and class. Black and brown children and teens are disproportionately still diagnosed with the stigmatized oppositional defiant disorder when showing the same distressed behaviors as white PDA-identified counterparts (though many white youth still get ODD diagnoses). Higher income families are more likely to afford neurodivergent-affirming providers who flag PDA instead of ODD. Meanwhile, a diagnosis of ODD can lead to interventions that further distress any nervous system, especially one with a very sensitive trigger around loss of autonomy and social equality. Youth can end up in cycles of distress or the school-to-prison pipeline, instead of accommodated and supported. (Thanks to @BlackSpectrumScholar for raising the alarm on race and class disparities in PDA).

Although PDA is not yet recognized in any diagnostic manual, some clinicians in the U.S. and U.K. are listing it under an autism diagnosis as an unofficial subtype. Some critics question whether PDA is real, pointing to the lack of research and lack of official recognition. Others say that pathological demand avoidance is simply a trait that co-occurs with many diagnoses, including ADHD, OCD, and PTSD.

But the reality is that unaccomodated PDAers struggle in daily life. We may be unable to do things that threaten our sense of autonomy, even if we’d otherwise enjoy the task. This explained why my child could spend an hour playing in the sink but went into full fight-mode when I asked him to wash his hands. We may subconsciously create and follow strict rules about how we do tasks in order to maintain a sense of control over the demand that we do them. This explained why I had strict food rules that had nothing to do with taste or texture. And we will often assert power or status over other people to feel safe. This explained my knee-jerk need to know all the answers in any context and my child locking my husband at home when it was time for work. (These behaviors are known in the community as “equalizing,” a term coined by parent coach Casey Ehrlich.) Essentially, PDAers are extraordinarily vulnerable to threat responses and dysregulation throughout our lifespan, and our nervous system capacity is low.

Diving into the PDA community, I learned about specific accommodations that would support me and my son: lowering demands, emphasizing equality and collaboration in relationships, granting bodily autonomy, allowing for extra rest and retreat, using declarative language, and taking effective anxiety medication, to name a few.

Unfortunately, this knowledge came too late to save my child from PDA burnout. By his second winter in an inclusion preschool, just as we were learning about PDA, my child lost interest in his friends. His varied diet shrank to a handful of foods. Meltdowns became more frequent. Drop-off rituals got longer and longer, until one morning school called: he was careening around the classroom, sobbing for me.

His teacher wanted me to keep him there, lest he “have a harder time returning tomorrow.” But I was done taking advice from the so-called experts. If I continued down this road, I knew I’d lose both my child’s mental health and his trust. So I drove across town, picked him up, and brought him home from school for the last time.

At the start of burnout, my son was unable to even tinker with the engineering sets that once delighted him, and instead watched YouTube for 10 hours a day. I curled on the couch beside him, nuzzling his neck and breathing out slowly, lending him my regulated nervous system as best I could. My husband and I dropped expectations around screentime limits, mealtimes, and manners. If he panicked when we were out of a popsicle flavor, one of us hopped in the car and bought a new box. The priority was not to teach our child limits, but to teach his body what safety felt like, so that he could come out of threat response and eventually be able to learn, play, and grow again.

As we dropped demands that were too hard for my child’s nervous system, I began to see all the ways I had habitually disrespected my own. The long conversations, the crowds, the nonstop meetings, the four decades of life as a high-achieving student, activist, and rabbi. I’d been caught in what I now know is a classic PDA conundrum: I loved the social stimulation and my exciting work, but my nervous system didn’t. I’d spent hours a day internally dysregulated, eventually landing in periods of burnout myself. My threat response impacted my romantic attachment style, marriage, and relationship to the world at large.

It wasn’t just my son who needed a different life.

I did too.

It took months of coregulation, low-demand parenting, and Prozac, but the light began to return to my son’s eyes. Instead of wrestling him out the door to school in the mornings, we snuggled under a weighted blanket, watched YouTube, and cracked each other up inventing tongue twisters. Instead of fighting about handwashing in the afternoons, he engineered machines in Minecraft while I worked on freelance writing projects. In this new life, with unlimited access to his special interests and insulated from the demands that triggered his threat response, I saw proof that dysregulation and demand avoidance were not innate to my child. They were expressions of his nervous system in distress.

We were in the privileged position to accommodate him without worrying about losing our jobs or home. I lost sleep worrying about PDA or ODD families who didn’t have that privilege: the kids who were forced to continue attending school well past their nervous systems’ breaking point, who went into psychiatric and behavioral crises and often suffered violent disciplinary action at the hands of school police; and the adult PDAers facing burnout and unemployment without financial security.

With these concerns in mind, I shifted my career to coaching PDA adults and parents of PDAers with an equity-based fee scale. I wanted to ask more than just how to help PDAers out of burnout. I wanted to articulate how we might craft lives that work for our vulnerable nervous systems so that more people could be safe and well. Over time, thanks to analyzing my own lived experience, working with my clients, and studying with several wonderful PDA thought-leaders, I began to articulate something new: The PDA Safe Circle, a strengths-based approach to decreasing distress and increasing thriving for PDAers of all ages.

The approach is visual, intuitive, and highly actionable, and unlike many resources out there, it applies across the lifespan, not just to parents with PDA kids. Buoyed by the impact I’ve seen with my clients, I spent the last year working on launching The PDA Safe Circle as an app, course, and online community for PDAers and our loved ones. The community launched in late February, and I’ll be offering certification in The PDA Safe Circle Approach to coaches and clinicians, and eventually educators, as well. The project is tremendously fulfilling, combining my background in community organizing, pastoral care, and congregational leadership with my current special interest in PDA and autism.

If you’d asked me five years ago where my career would be now, I never would’ve imagined I’d have an unconventional rabbinate serving a community of neurodivergent people and our family members from all over the world. I barely knew what the word neurodivergent meant back then, let alone PDA. But in this new career, I’m able to embody my full, unmasked self to make a transformative impact in people’s lives, all while working remotely on my own schedule. The new life I needed has become manifest.

I love when my seven-year-old son makes a guest appearance in a coaching session, popping his wide smile on Zoom to share an insight about his burnout or his own safe circle. I tussle his dark hair and wrap my arm around him, filled with gratitude. In a different generation, a kid with his threat response would likely have been institutionalized. Instead, my beautiful boy is thriving in a loving home that understands his disability, celebrates his strengths, and works to make the world safer for him and all of us.

Rabbi Shoshana Meira Friedman

Rabbi Shoshana Meira Friedman is the creator of The PDA Safe Circle™, which is now an app, course, and online community for PDAers and their loved ones, with training for clinicians rolling out soon. Her writing has been published in many venues including the New York Times, and she’s the author of the picture books The Tide Is Rising, So Are We!: A Climate Movement Anthem and Playground Count Along: For Young Children and Gestalt Language Processors. Contact: PDASafeCircle.com and RabbiShoshana.com. @rabbishoshana on Instagram.