In the fall of 1987, a story appeared in the business section of The New York Times about a new antidepressant drug, fluoxetine, which had passed certain key government tests for safety and was expected to hit the prescription drug market within months. Just this brief mention in the Times about the prospective appearance of the new, perkily named Prozac propelled Lilly shares from $10 to $104.25—the second-highest dollar gain of any stock that day. By 1989, Prozac was earning $350 million a year, more than had been spent on all other antidepressants together in 1987. And by 1990, Prozac was the country’s most prescribed antidepressant, with 650,000 prescriptions filled or renewed each month and annual sales topping $1 billion. By 1999, Prozac had earned Lilly $21 billion in sales, about 30 percent of its revenues.

Back in the 1970s, Prozac didn’t look so promising when Lilly, a company then known for producing antibiotics, began working on it. Serious depression—which warranted hospitalization, perhaps electroshock, or a gaggle of psychiatric medications, many with appalling side effects—was viewed as a debilitating but rare condition, thought to affect only 1 in 10,000 people. Less paralyzing depression symptoms were regarded mostly in psychodynamic terms, such as “depressive reactions” or “depressive neuroses.” After all, what relevance could a “chemical imbalance” possibly have for issues like “retroflected anger” or “oral introjection” or “identification with the lost object”?

Lilly had planned to market its new drug for hypertension or maybe anxiety, but fluoxetine just didn’t seem to work at lowering blood pressure, and the tranquilizer market had nose-dived after people had learned to their horror that Valium and Librium—“mother’s little helpers”—were turning perfectly respectable middle-class ladies into addicts. Lilly then tried using fluoxetine as an anti-obesity agent, but that didn’t work either. Nor did it relieve symptoms of psychotic depression: it actually made some people worse.

And then, according to psychopharm folklore—maybe because they had nobody left to try it on—they gave fluoxetine to five mildly or moderately (stories vary) depressed people, all of whom then felt much better. Bingo! Therein lie the origins of this little med with the zippy brand name, which set in motion a vast antidepressant empire, as well as the longest, most remunerative gravy train in psychopharmaceutical history. Prozac begat a dynasty of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) with their tongue-twisting generic and user-friendly brand names—fluvoxamine (Luvox), paroxetine (Paxil), escitalopram (Lexapro), and so on. They, in turn, were followed by the “atypical antidepressants,” including bupropion (Wellbutrin), vanlafaxine (Cymbalta), and mirtzapine (Remerona). By 2008, 11 percent of Americans (25 percent of women in their 40s and 50s) were taking one of about four dozen brand-name antidepressants. These antidepressants were the most commonly prescribed medications in the country (now, in 2014, they’re a few percentage points behind antibiotics) and brought $12 billion a year to the pharmaceutical companies.

How did this happen—and by what scientific, psychiatric, marketing, sociological alchemy? As it turns out, this wasn’t the first time Americans had fallen hard for a haphazardly discovered, but perfectly legal, respectable, and medically approved psychoactive agent that was easy to take and provided quick relief from certain relatively blurry categories of physical and mental suffering. Over the last 150 years or so, we’ve seen successive waves of mass infatuations with psychotropic drugs—morphine, heroin, cocaine, amphetamines, barbiturates, tranquilizers, and antidepressants. While all these drugs are different, the story arc they follow—their rise, triumph, ascendancy, and gradual decline or sudden collapse—does follow a roughly predictable course.

Opium, Heroin, Cocaine

In the beginning was opium—or its derivative, morphine. Although it didn’t exactly have a “debut” in America, having been part of the social zeitgeist since the late 18th century and a fixture of human history since the fourth millennium BCE, it became far and away the country’s most important reliever of psychic and physical pain. Reaching virtual market saturation by the 1880s, it was as widely, freely, and indiscriminately used for just about every ailment as Tylenol or Advil are today. Recommended by physicians, advertised copiously in medical journals and the popular press, easily bought without a prescription form at the local pharmacy or general store, and available by mail order, opiates were taken in pills, tablets, cough drops, liquids (often mixed with alcohol and cannabis for a really good buzz), and plasters. It was the sovereign remedy for that 19th-century, catch-all disorder, “neurasthenia,” sometimes called “Americanitis,” because it was brought on by the conditions of American life: the hustle and bustle of expanding cities, the frenetic growth of commerce and industry, the feverish competition for money and power, which strained people’s nervous energies to the breaking point.

Morphine, the injectable alkaloid derived from opium, was considered superior to opium because it was stronger and thought to be nonhabit forming. As injected, it was even considered a cure for opium addiction. (The only downside to this theory, of course, was that morphine was even more addictive.) American Civil War vets getting morphine injections to relieve the lingering pains of war wounds continued taking it decades after the war to feed their habit. Mothers gave it to colicky newborns and teething babies. And while men drank alcohol openly in saloons, opiate-addled ladies nodded off quietly in their parlors or dosed themselves in secret before heading off to the theater or opera.

Opium or morphine was, in fact, the ladies’ drug of choice, or at least the drug of their doctor’s choice. Women were given opiates for “female troubles’’—from menstrual problems to the pains of childbirth. In addition, because of the innate delicacy of the female nervous system, they were thought to be more susceptible to neurasthenia and melancholy than were men. By the late 1860s, more than two-thirds of the public, 80 percent in some places, estimated to be opiate addicts were white, middle-class women. But besides relieving physical pain, women undoubtedly found morphine to be as good an escape from the tedium of daily life as they were likely to find. As one female morphine taker, “a lady of culture and distinction,” wrote in 1909, “[D]on’t you know what morphine means to some of us, modern women without professions, without beliefs? Morphine makes life possible. . . . I make my life possible by taking morphine.”

Altogether, by 1900 more than four percent of the American population was addicted to opiates—a bigger percentage of the population than heroin addicts in the 1990s. Even by the 1880s, however, the medical community as a whole was beginning to perceive opiate addiction to be a threat to the mental and physical health of the republic. What to do? Luckily, at about that time, the next big, bright idea on the pharmaceutical scene was born—which itself would become a kind of proto-blockbuster. This was heroin, a synthetic introduced in 1898 by a German company known for making color dyes and owned by one Friedrich Bayer. The company had another little compound in the works called acetylsalicyclic acid (or aspirin). But they put it on the back burner to focus on what they thought would be a bigger money-maker, heroin (so-named because, twice as strong as morphine, it was considered heroisch, the German word for ‘heroic’). Bayer and his company massively promoted their new drug in its adorable little bottle, sent out free samples to physicians, and advertised it as an effective, nonhabit-forming drug—a great cough suppressant and, again, a good source for demorphinization, the process of weaning addicts off their morphine.

The drug was a huge commercial hit in America but, within a few years, it was painfully obvious to most that the hype had been a shade too positive: heroin was far more addictive than morphine. Bayer stopped making it in 1913 (whereupon it, too, would go on to a booming career as an illegal street drug) to get rich instead on the sales of that other compound the company had laid aside, aspirin, which itself turned out to have quite a nice run.

In the meantime, what would replace the fading reputation of the opioids? In 1884, a young physician named Sigmund Freud wrote his first important monograph on a drug he’d been experimenting with on himself. The monograph was “On Coca,” and the drug was, of course, cocaine. Although shortly thereafter, he’d have serious regrets about his new find, at the time, he sounded like a classic cokehead enthusiast. Cocaine, he wrote, promoted “exhilaration and lasting euphoria, which in no way differs from the normal euphoria of the healthy person.” There was no unnatural excitement, no “hangover” effect of lassitude, no unpleasant side effects and, best of all, no dangerous cravings for more. Cocaine, Freud believed, could be not only a mental stimulant, but a possible treatment for “nervous stomach” and other digestive disorders, asthma, and once again, morphine and alcohol addiction. To his fiancée, Martha, he wrote, “I take very small doses of it regularly against depression and against indigestion and with the most brilliant success.”

Freud certainly didn’t introduce cocaine to America. In fact, it was introduced to him via promotional materials sent by Parke, Davis & Company (soon to become the world’s largest producer of pharmaceutical-grade cocaine), who eventually paid him to say something nice about the drug. By this time, cocaine infatuation was well underway in Europe and America. In contrast to the drowsy, dreamy languor induced by the opioids, cocaine woke people up, gave them new vim and vigor, and increased their optimism and self-confidence to forge ahead in life. As Stephen Kandall writes in his book Substance and Shadow: Women and Addiction in the United States, fashionable women visited their doctors for hypodermic injections of cocaine “to make them lively and talkative” in social situations.

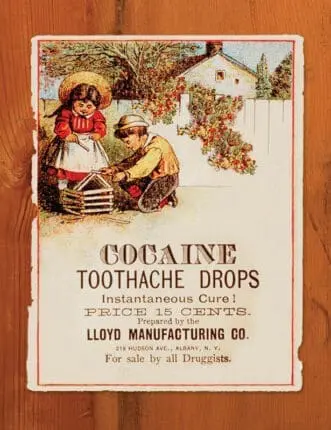

Parke, Davis & Company produced a clutch of cocaine-based products (as did other companies), including wine, soft drinks (to compete with Coca-Cola, made by a Georgia company), cigarettes, a powder that could be inhaled, and an injectable form with a hypodermic kit. Cocaine would, the Parke, David & Company promotions read, “supply the place of food, make the coward brave, the silent eloquent and . . . render the sufferer insensitive to pain.” Wonderfully enough, among the innumerable products containing cocaine made by different companies was a soda simply and perfectly called Dope.

But, like opium before it, cocaine gradually lost its bloom with the growing awareness that this addiction was, yet again, possibly even worse than those of opium and heroin. Unlike the opioids, which rendered people semiconscious, too much cocaine made people crazy—hallucinatory, psychotic, violent. As middle-class users fell away, cocaine became increasingly associated with the lower orders of society, making it even scarier to polite society. Gradually, beginning in the early 20th century, and particularly after the Harrison Act of 1914, increasingly stringent laws severely tightened the sale and distribution of these drugs, as well as cannabis. They then went underground, only to emerge 50 to 60 years later as part of a huge, and still apparently unstoppable, illegal drug trade.

Barbiturates

After a kind of pharmaceutical respite, the 1930s saw the more or less parallel rise of uppers and downers in the form of amphetamines and barbiturates. Both would be extolled, in the same familiar way, as perfectly safe, nonaddictive, and wonderfully effective for a wide variety of physical and mental ailments.

The first barbiturate drugs, synthesized and marketed in 1911 by Merck and Bayer under the brand names Veronal and Luminal, proved themselves hugely more effective as soporifics than previous nostrums—like the bromides, which had terrible side effects and took 12 days to work themselves out of the body. The first intravenous anesthetic, they dampened down the central nervous system without necessarily knocking people out. By the 1920s, they were being used to relieve surgical and obstetric pain, control seizures and convulsions, ease alcohol withdrawal symptoms, soothe ulcers and migraines, suppress asthmatic wheezing, and reduce the irritability accompanying hyperthyroidism.

The biggest selling point of the barbiturates, however, was that they made people feel pleasantly drunk and sleepily euphoric, so it only seemed natural that they might be a good drug for soothing the perpetually anguished and agitated American psyche. Thus, the drugs soon acquired a reputation as the psychotherapist’s friend. One psychiatrist, in fact, claimed in 1930 that Amytal not only quickly dispatched “manic-depressive psychosis” symptoms, but also midlife depression, with “complete recoveries in two to four weeks.” Amytal was marketed to psychoanalysts for “narcoanalysis” because it relaxed fears, anxieties, and inhibitions and engendered childlike trust in the therapist—features of the drug that, coincidentally, attracted law-enforcement authorities, who used it as a truth serum to ease confessions out of befuddled suspects.

During World War II, barbiturates were given widely to soldiers, not only to assuage the pain of wounds and ease the dying, but to help military personnel in the South Pacific cope better with the heat. Barbiturates (goofballs, as they were called) lower blood pressure and respiration—which had the double effect of preventing overheating and calming battle fear. When soldiers returned home, many were also given barbiturates from psychiatrists to help them “process” their traumatic memories. Undoubtedly, the surge of returning GIs and their barbiturate habit contributed to the skyrocketing use of the drugs during the late ’40s and first half of the ’50s. Adding to their appeal, goofballs came in a range of pretty colors and shapes, with cute names to match: yellow jackets, blue angels, pink ladies, and reds.

Pharmaceutical companies had only recently begun making pills in different colors, which not only appealed to customers and distinguished one brand from another, but made the drugs safer: you weren’t as likely to mistake your yellow jacket for an ordinary aspirin when you popped a couple into your mouth before bed.

Like their much-loved predecessors—morphine, cocaine, and heroin—the barbiturates too proved to have just one or two tiny glitches that kept them from being the perfect way to wind down after a stressful work day. Not only were they habit forming, with dangerous side effects, but they allowed scant room for dosage error—a little too much more than a strictly therapeutic amount could, and often did, kill people. Compounding the risk, they were known to produce a so-called automatism phenomenon: people would take a pill, forget they’d taken it, take another, and then perhaps if they were still conscious, forget they’d taken that one and swallow a third—a routine that could clearly end badly. Between 1957 and 1963, in New York City, there were 8,469 reported cases of overdose and 1,165 deaths. By 1962, an estimated 250,000 people were addicted to or dependent on barbiturates.

The absolute number of addictions and deaths may not seem strikingly high, particularly compared with the number of alcohol abusers then and now. But by the ’50s and ’60s, there was a steady drumbeat of influential media stories about barbiturate-caused overdoses, hospital stays, and suicides of celebrities (Marilyn Monroe’s death was headline news), average businessmen, housewives, politicians, and various members of the hard-working middle class. “Grave Peril Seen in Sleeping Pills,” ran the title of one 1951 story in The New York Times, which claimed that barbiturates “are more of a menace to society than heroin or morphine.” Undoubtedly, the decline in barbiturate consumption was hastened by these fearful tidings, as well as by more stringent laws pursued by medical and political authorities.

Amphetamines

The amphetamines arrived somewhat later, but soon—as befits a drug with the nickname speed—shot to the top of the market even as the barbiturates were slouching their way through the American psyche. As Nicolas Rasmussen reports in On Speed: The Many Lives of Amphetamine, the story begins in 1929. An American chemist named Gordon Alles was trying to develop a commercial drug for asthma that would challenge ephedrine, an herb-derived med already hugely successful but difficult to obtain (the plant came from China) and often in short supply. The chemist noted, after injecting himself with the drug—in those days, experimenting on oneself was considered the only honorable way to begin testing a drug—that while it did clear his nose somewhat, it raised his heart rate and blood pressure and, moreover, gave him a remarkable feeling of well-being. He also noted that it made him more talkative and, he felt, wittier than usual.

In 1934, Alles joined the pharmaceutical firm Smith, Kline and French (SKF), which already had patented an asthma inhaler with an amphetamine base. (Alles maintained that the company had gotten the idea from his work.) Although they realized that their new drug, which they called Benzedrine Sulfate, had certain effects on circulation, blood pressure, and muscle movements, as well as that curiously enlivening impact on the brain, they had no idea what it could be used for. So SKF sent out free samples to any doctor who showed an interest and ran some studies—on dysmenorrhea, allergies, asthma—with poor to mediocre results, as well as on narcolepsy and Parkinson’s, on which it seemed to work better. Since the company needed a bigger market, however, they tried it on volunteers to see if it enhanced mental performance—and hit an unexpected jackpot.

Although Benzedrine Sulfate didn’t actually improve thinking ability, what it did do, from a marketing standpoint, was even better. It almost magically lifted people’s spirits, increasing their optimism, self-confidence, sociability, mental alertness, and initiative. The researchers tried the pill on children with learning and behavioral problems and noted that it seemed to help. Paradoxically, while revving up adults, it seemed to calm down unruly kids, though the ultimately explosive ramifications of that discovery wouldn’t be revealed for decades. Yes, the drug tended to make people more aggressive, but it made them feel positive and confident, too. So the company had a winner!

When Benzedrine Sulfate debuted in 1937, SKF sent out mailers to almost every member of the American Medical Association (90,000 doctors) with this simple message: “the main field for Benzedrine Sulfate will be its use in improving mood.” Ads that followed marketed it for “the patient with mild depression,” but not severe depression or schizophrenia or anxiety (it made the last two worse). Symptoms of this “depression” that Benzedrine Sulfate promised to relieve closely paralleled the familiarly vague miscellany associated with neurasthenia: apathy, discouragement, pessimism, difficulty in thinking, concentrating and initiating usual tasks, hypochondria—that same generic, hard-to-define sense of “unwellness” in body and mind that seemed to be a perennial affliction among Americans.

The marketing effort was helped immeasurably when a leading psychiatric expert at Harvard, Abraham Myerson (the drug industry would today call him a “key thought leader”), took up the cause of Benzedrine Sulfate as a nearly infallible remedy for what he called idiopathic anhedonia—a condition of apathy, low energy, lack of motivation, and inability to take pleasure from life. Myerson himself liked the way amphetamine made him feel (it would turn out that doctors enjoyed taking speed as much as prescribing it) and thought it worked wonders at cheering “anhedonic” people up, giving them more pep, vigor, and gusto for life. So it happened that Benzedrine Sulfate became, in effect, the world’s first prescription antidepressant, not to mention the first, and probably only, prescription medication intended for a condition called, simply, “discouragement.”

Once Benzedrine Sulfate was launched upon the world, the rush was on. Of course, college students—always willing guinea pigs for any new mind-altering substance, legal or illegal—already loved the inhalers because they not only kept them awake and alert, but seemed to improve their powers of concentration, even their thinking ability. By 1937, they were using them enthusiastically for all-night cramming to an extent that alarmed college authorities and warranted a brief article in Time calling the drug “poisonous.” In fact, by the end of World War II, amphetamine-based decongestants of many different brands were available everywhere, easily bought without prescription—but not very often, it would seem, for the purpose of clearing one’s nasal passageways. People routinely broke open the inhaler and ate the amphetamine-soaked paper contents.

During World War II, American and British soldiers kept Benzedrine in their emergency kits along with Band-Aids, hydrogen peroxide, morphine solution, tweezers, burn ointment, scissors, and whatnot. Not only would the drug keep military men awake and alert—on long bombing runs, for example—it would shore up morale. For this, the drug worked sensationally well, too well, in fact. Sure, it increased soldiers’ confidence and fearlessness, but also their foolhardiness, often worsening performance and judgment. There was also the problem of hallucinations and paranoia following amphetamine-caused sleep deprivation, not to mention the addictiveness. In On Speed, Rasmussen estimates that about 15 percent of the 12 million servicemen probably became regular users—a habit they brought back home with them after the war. During the Vietnam War, the United States dispensed more amphetamine to its troops than the British and Americans had done throughout World War II.

After the war, the drug went civilian big-time. A whole generation of beatniks, musicians, writers, and other aficionados of “cool” took their doses of amphetamines, either as inhaler paper wads or pills. Indeed, Jack Kerouac’s On the Road is a kind of long prose poem to speed. But it was in the perfectly legitimate world of mainstream medical practice during the ’50s that amphetamine really hit its stride. The times were particularly friendly to psychiatrists (who’d played an active role in the war, screening soldiers and treating combat fatigue) and to psychoanalysis. The public readily accepted the analytic concept of “neurotic depression”—referring to a grab bag of quotidian suffering caused by family strife, financial worries, overwork, life dissatisfaction, anxiety, and/or various specified depression-inducing conditions, such as physical disease, chronic pain, and old age. And for the first time in American history, medical authorities now claimed that a large percent of the population was mentally ill: 1 in 10, they estimated. Since there weren’t enough trained psychiatrists to take care of all these people, general practitioners would have to step in and act in loco psychiatrist, so to speak. These doctors didn’t do analysis, but they sure could do the next best thing: prescribe amphetamines.

Then in the late ’40s, amphetamine makers hit the jackpot when they concocted a mental/physical condition for which their drug was the most perfectly marketable solution: fatness plus depression. Whereas being overweight was once associated with slow metabolism or, say, piggish overeating, now it was described as a psychosomatic problem, caused by a mental illness, most likely depression. For years, doctors had prescribed amphetamine pills off-label for weight loss, but in 1947, SKF began marketing both Benzedrine and a new product, dextro-amphetamine (brand-name Dexedrine), specifically for this purpose, citing emotional disturbance as a direct cause of weight gain and, as an added spur, reminding doctors that even a few extra pounds were potentially dangerous.

Between 1946 and 1949 (when Dexedrine lost its patent), SKF’s annual amphetamine sales rose from $2.9 million to $7.3 million—which doesn’t count the proliferating sales of D&D (diet and depression) products based on methamphetamine, a newer synthesis, invented by other companies to compete with Dexedrine. When Dexedrine was released as a “spansule,” a time-release capsule, sales rose from $5 million in 1949 to $11 million in 1954—not including new, proliferating competitors (some by SKF itself), with vaguely space-age names like Eskatrol, Thora-Dex, AmPlus Now, Opidice, Obedrin, and so forth.

This perfect dream of a drug only had one flaw: it made people feel jittery, edgy, jumpy, and agitated—and many people seemed to find that more pep and energy weren’t worth a chronic case of the heebie-jeebies. The answer was, once again, a stroke of marketing genius: combining amphetamine and barbiturate in one all-purpose, upper/downer drug that would elevate people’s moods and mellow them out at the same time—and help them lose weight in the bargain! The first such pill was called Dexamyl, a combination of Dexedrine and Amytal (the barbiturate) packaged in a bright blue, heart-shaped little tablet and promoted to relieve anxiety and depression—as one glossy brochure put it, “for the management of everyday mental and emotional distress.”

By 1960, Rasmussen estimates that amphetamines accounted for about three percent of all prescriptions sold in the United States and Great Britain, and by 1962, US production of amphetamine was 80,000 kilograms per year; that’s 8 billion tablets, or enough for 50 tablets a year for every person in the United States. By the mid-’60s, however, the truly appalling downside of amphetamines (withdrawal symptoms like panic, nightmares, seizures, severe depression, hypersomnia followed by hyposomnia, as well as the psychotic features afflicting people who started taking the drug with a doctor’s prescription and then just couldn’t stop) were becoming hard to ignore. There were exceptions: amphetamine’s die-hard champions, including psychiatrists, ignored or rationalized away such side effects, even arguing that abusers were rare and abused the drug only because they had weak personalities to begin with, or preexisting schizophrenia, which the drug simply uncovered.

Nonetheless, amphetamine use did decline, in part because of the growing publicity about the ugly consequences of abuse. There was also widespread, media-broadcast concern about the huge amount of it being diverted to street use (80 to 90 percent of the drug seized on the street was in the form of pills made by US pharmaceutical firms). Nor was the drug’s respectability helped by the widely publicized, extremely unattractive spectacle of hippy speed freaks injecting their dirty, long-haired selves with homemade products and then going violently bonkers. After a decade of only marginal success at trying to control prescription drug abuse, the FDA managed in 1971—in the teeth of Big Pharma opposition—to define amphetamine and methamphetamine as Schedule II drugs, meaning they had a high potential for abuse and could be dispensed only in nonrefillable prescriptions, with strict record-keeping required.

As the new rule was announced, but before it went into effect, amphetamine prescriptions suddenly jumped 60 percent, a bit like the sudden rush to stock up on firearms at rumors that stricter gun laws are imminent. A year later, the medical use of amphetamine had dropped to one-tenth of what it had been before the law had changed. Until the next legal speed epidemic—a new crop of amphetamine-like diet drugs (some with deadly side effects) during the ’90s and runaway prescriptions of stimulants for children with ADHD in the 2000s—medical use of amphetamines declined, though the illegal production and sale of both homemade and imported methamphetamine exploded. In 2006, the UN declared it the most abused drug on earth.

Tranquilizers

Meanwhile, Americans, tense and strung out as always, were being introduced to yet another new pharmaceutical miracle and boffo hit in the marketplace: the minor tranquilizers.

Miltown, aka meprobamate, almost didn’t make it to market. In 1951 or so, doctors weren’t much interested in a drug for ordinary, everyday anxiety; this was a psychoanalytic, not a medical or biological problem. Besides, doctors already had their choice of barbiturate sedatives for calming people down, amphetamines for perking people up, and drugs like Dexamyl for doing both at once, thank you very much. Thus, the company producing the drug lost interest in promoting it. What was the point, if there wasn’t a market? Yet Frank Berger, meprobamate’s inventor, soldiered on, sending experimental batches of the pills to psychiatrists to try out on their patients. They reported back that the drug worked wonderfully: it made people less tense and irritable, more relaxed and happily productive during the day, better able to sleep at night, without the risks of the wooziness, addiction, and sudden death associated with barbiturates or the buzz-crash-burn, addiction, and psychosis cycle of amphetamines. The drug even seemed to alleviate mild depression, insomnia, and neurodermatitis!

Berger wanted to call his new pill a “sedative,” but was talked into the less overused, more poetic term “tranquilizer”—which seemed right, since rather than knocking people out, it made them more calmly alert and focused. Berger’s team also decided to name their new little prince of peace Miltown, after an idyllic, old-fashioned village near their company, called Milltown. (They dropped one “l” since they couldn’t patent a place name.) And lo, it came to pass that in March 1955, the new drug was released to the public.

To start, it was almost completely ignored. In the first month, writes Andrea Tone in The Age of Anxiety: A History of America’s Turbulent Affair with Tranquilizers, it sold a paltry $7,500. But when it caught on, did it ever! Sales went up to $85,000 in August of that year, to more than $2 million by Christmas. By 1957, more than 36 million prescriptions had been filled for meprobamate in the United States alone, more than a billion pills had been manufactured, and the drug was accounting for fully a third of all prescriptions written.

Why? Possibly, the very fact that it was billed as such a moderate solution to the chronic nervous anxiety that had afflicted Americans since the country was founded made it seem indispensable to upwardly mobile men and women chugging away in the postwar economic boom. They needed a drug that wouldn’t leave them silly-high or dozy—something that would take the edge off chronic anxiety, give them a boost in the marketplace if they were men, and keep them from going nuts with frustration and boredom if they were housewives. Really, Miltown was a family drug. As the “executive Excedrin,” it helped the man in the gray flannel suit claw his way to the top (smiling!); it was yet another sovereign remedy for the always fraught condition of being female (menstrual nerves, menopausal depression, harried-housewife syndrome, and painful intercourse, aka, frigidity); and even children got their Miltown to stop nervous tics, tantrums, school headaches, stammering, and biting dentists’ fingers.

What clearly helped sell Miltown to millions of people in the first place was the sudden, explosive celebrity mania for the drug, particularly in greater Los Angeles, which became known as Miltown-by-the-Sea. In fact, so many show-biz types loved Miltown that it became a television comedy meme, with comedians wisecracking about the pills, even as they were tossing them back like M&M’s. Jerry Lewis, Red Skelton, Bob Hope, Jimmy Durante, and Milton Berle incorporated Miltown jokes into their routines. In 1958, Salvador Dalí was commissioned to do an art installation for the Miltown exhibit at the American Medical Association’s annual meeting. It was a silk-sided, undulating tunnel that people could walk through, with Dalí’s slightly creepy murals on the side symbolizing the transition from anxiety to tranquility.

Meanwhile, Equanil, a carbon copy of Miltown, debuted at the same time by agreement with another pharmaceutical company, was being marketed only to doctors, who felt that the crass, showbiz-tainted promotion of Miltown to the unwashed masses was beneath the dignity of their profession. Soon, because doctors backed and recommended Equanil and not its cheesy (but chemically identical) twin sibling, its sales outpaced Miltown’s. By 1959, 19 different companies were making me-too tranquilizers, and Miltown’s reputation was flagging. Over the next few years, it would paradoxically be judged both relatively ineffective—a namby-pamby kind of party drug—and highly dangerous. This double message—a drug that was too weak, but also too strong—was summed up by Time in 1965, the year Miltown was dropped from the US pharmacopeia. “Some doubt that it has any more tranquilizing effect than a dummy sugar pill,” the article read. “Others think that it is really a mild sedative that works no better than older and cheaper drugs, such as the barbiturates. A few physicians have reported that in some patients Miltown may cause a true addiction, followed by withdrawal symptoms like those of narcotics users ‘kicking the habit.’”

Nighty-night, Miltown! But even before Miltown began drifting off into oblivion, the drug companies had their periscopes up and swiveling around in search of the next Best Drug Ever. Soon enough, Hoffman-LaRoche (Roche), a pharmaceutical company in New Jersey, had a new blockbuster, which would not only out-blockbuster all previous blockbusters, but wouldn’t itself be out-blockbustered until the advent of the godlike Prozac in 1987. Actually, the inventor, Leo Sternbach, came up with two similar blockbusters, both based on his newly created class of chemicals, the benzodiazepines. The company named them Librium (from the last syllables in equilibrium), released in 1960, and Valium (from valere, the Latin verb meaning ‘to be in good health’), released in 1963.

Roche pushed the development of Librium by relentlessly promoting the drug’s originality and difference from the rest: “completely unrelated chemically, pharmacologically, and clinically to any other tranquilizer.” Librium’s other major selling points were its greater potency and versatility: it would presumably help more and different kinds of people with a wider range of problems than anything else on the market. As in every such promotional campaign, Librium’s makers insisted that the drug had no bad side effects and was completely unaddictive (this time, we really mean it!). And they set out to convince the world that it would help absolutely anybody, from the mildly to severely impaired, who wasn’t flat-out crazy (and it might help even some of them, too). This included a wide spectrum of impairment, including the middling group of so-called psychoneurotics, the ones with agitated depression and severe anxiety, as well as just about every other category of mental misery, such as chronic alcoholism, phobias, panic, obsessive-compulsive reactions, “schizoid” disorders (excessive detachment and social avoidance), epilepsy, emotionally generated physical symptoms (skin disorders, gastrointestinal issues), and narcotics addiction. The drug showed its chops with volatile prisoners, apprehensive college students, hysterical farm wives, querulous elderly people, and those old standbys of the perfectly normal, all-American nuclear family: the tense businessman with heartburn; his moody, premenstrual, sex-avoiding wife; and their unruly, school-phobic child. Three months after its introduction, Librium had become the most often prescribed tranquilizer in the world, with American doctors writing 1.5 million new prescriptions for it every month.

Three years later, Valium was introduced to the market, probably just to keep the exploding market for tranquilizers firmly in the Roche camp. If Librium had been a hot-ticket item, Valium was a supernova. Substantially more potent than Librium, but without Librium’s bitter aftertaste, it was the first drug brand in pharmaceutical history to hit $100 million in sales, rising to $230 million by 1973, and a cool billion by 1978, when 2.3 billion tablets were sold. Between 1968 and 1981, it was the most widely prescribed medication in the Western world. No wonder that in 1975, Fortune Magazine called the benzodiazepines, “the greatest commercial success in the history of prescription drugs.”

Tranquilizers were vastly successful among both men and women, but they seem to have had a special place in the lives of women. Even though, as Tone points out, slightly more ads for Valium were directed toward men, the different ways male and female anxieties were presented and used to sell drugs were telling. Whereas men’s anxieties produced real, life-threatening bodily ills, the physical ailments provoked by women’s anxieties often showed up as hypochondria or “female troubles,” related to menstruation, sexual difficulties, and menopause. One prominent Valium ad features a woman standing alone on a cruise-ship balcony with the accompanying title “35, single and psychoneurotic.” The copy goes on to say that “Jan” has low self-esteem, hasn’t found a man to measure up to her father, and now feels lost because she realizes she may never marry. It suggests that whether in conjunction with therapy, or all by its own little self, Valium could relieve the anxiety, apprehension, agitation, and depressive symptoms that somehow keep Jan from finding the man of her dreams. In the late 1960s, women were the biggest consumers of psychotropic drugs, accounting for 68 percent of all antianxiety drugs prescribed. But that same year, they were also prescribed 63 percent of all barbiturates, 80 percent of all amphetamines, and—20 years before Prozac—71 percent of all antidepressants.

By the early ’70s, Valium was still on a roll, with Librium not too far behind. So successful were the drugs, so popular, and apparently so immediately effective at soothing the savage beast that they actually succeeded in undermining the religion of psychoanalysis. How could anybody argue that anxiety was based on some buried inner psychic conflict when all it took was a pill to make all things bright and beautiful? In fact, during these years, both the medical community and the public began regarding anxiety less as a psychoneurotic problem than a biomedical one—a shift that would receive official sanction in 1980, when the newly published DSM-III first included generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) among its diagnostic categories. If ever a diagnosis seemed tailored to fit the drug prescribed for it, GAD was it.

Yet—low, ominous drum roll—dark clouds were beginning to dim the sunny skies of tranquilizer heaven. By 1975, although there were 103 million tranquilizer prescriptions a year in the United States, the reports of abuse and dependence were growing increasingly hard to dodge. By 1967, the FDA had collected enough complaints about the drugs to launch an investigation into their abuse potential, but bureaucratic inertia, drug industry pressure, and resistance among many Americans to having their favorite pills taken away stalled action for almost a decade. At the same time, however, the mass media were on the front lines of the story, particularly magazines aimed at women, such as Vogue, Ladies’ Home Journal, Good Housekeeping, and Ms. They ran articles describing people’s harrowing attempts to stop taking benzos: the intolerable rebound anxiety and depression, insomnia, headaches, agitation, tremors, even occasionally delirium and hallucinations (the sensation of bugs crawling all over the skin being one). Research studies appeared revealing that long-term use of tranquilizers actually increased people’s anxiety and depression, and caused their life-coping skills and personal grooming to go downhill. New trials on the drugs’ effectiveness demonstrated efficacy for the first week or two or three, after which they proved no better—and in some cases, worse—than placebo.

In 1978, it was sensational news when former first lady Betty Ford checked herself into rehab for her alcohol and Valium addiction. Then in 1979, television producer and documentary filmmaker Barbara Gordon’s book, I’m Dancing as Fast as I Can, about her self-destructive Valium addiction, became an international bestseller and was turned into a feature film, starring Jill Clayburgh and Nicol Williamson. The same year, Senator Ted Kennedy opened Senate Health Subcommittee hearings about the dangers of benzodiazepines, thundering that tranquilizers had “produced a nightmare of dependence and addiction, both very difficult to treat and recover from.” And the coup de grâce came in 1981 when John Hinckley, a deranged young man with a crush on movie star Jody Foster, attempted to assassinate President Reagan. As it happened, his psychiatrist had been prescribing 15 milligrams of Valium for him a day (he’d taken 20 milligrams just before the assassination attempt). One of Hinckley’s lawyers said that giving him Valium was like “throwing gasoline on a lighted fire.”

In the short run, benzo sales took a serious dive. The prescription rate fell from 103 million in 1975 to 67 million in 1981, to about 61 million in the mid-’80s. Valium prescriptions had fallen by nearly half. The release of newer tranquilizers—Klonipan (clonazepam) in 1975, Ativan (lorazepam) in 1977, Xanax (alprozolam) in 1980, and many others after that—let the tranquilizer market recover a good deal of territory (almost 86 million prescriptions in 2013). But even in recovery, the bloom was off the rose: the benzos had lost their prelapsarian innocence, and it would never again be possible to see them as no more worrisome than a nice, soothing cup of chamomile tea (but so much more effective!).

The Coming of Prozac

By the mid-’80s, there was a kind of existential void in the pharmaceutical feel-good market—but not for long. What would take the place of the tranquilizers, amphetamines, barbiturates, cocaine, and =opiates to help millions of people relieve the genuine, if often hard-to-define suffering of mind and body that seems such a perennial affliction of Western, certainly American, society? This brings us to the era of antidepressants, beginning with the totally unique, the unparalleled Prozac, which spawned many, many descendants—a psychotropic empire in full triumph and glory!

During its early, palmy years, Prozac seemed the answer to the depressed person’s prayers. There was a time during the early 19th century when the “melancholic” temperament was admired, at least in theory, as the mark of a sensitive, artistic soul, but in the 1980s, that time was past. Prozac was an all-American 20th-century go-getter sort of drug. It made people feel the way they thought successful people felt: self-confident but not arrogant, cheerful but not manic, cognitively on the ball but not hyperintellectual. And unlike so many other psychoactive drugs, the shiny little green-and-white capsule didn’t make people feel drugged, didn’t sedate them or jolt them into hyperconsciousness, didn’t send them drifting off into dreamy euphoria. Undoubtedly, some people taking Prozac felt “better than well,” as Peter Kramer famously wrote in Listening to Prozac, but most seriously depressed people were probably thrilled just to feel “normal,” able to go about their day with more emotional equilibrium than they’d experienced in years, if ever.

By 2011, the rate of antidepressant use had increased nearly 400 percent since 1991. By 2013, more than 40 percent of Americans had used an antidepressant at least once, and 270 million prescriptions were being written annually. And why wouldn’t people want them? Here was a class of drugs promoted as completely safe, without serious side effects, and effective for the wide-ranging symptoms of depression and anxiety and, increasingly over the years, obsessive-compulsive disorder, alcoholism, narcotics withdrawal, ADHD, eating disorders, bipolar disorder, PTSD, hypochondria, and so forth, as well as a long miscellany of nonpsychiatric conditions, including snoring, chronic pain, various neuropathies, chronic fatigue, overactive bladder, and so on. By now, thanks to their prevalence and a flood of direct-to-consumer print and broadcast ads, antidepressants are deeply familiar even to people who don’t take them.

But they’re not the benign, uncontroversial consumer product they might seem. Beginning a mere three years after Prozac’s introduction, negative side effects to the drug had already been noticed: intense agitation, tremor, mania, suicidal ideation. Not only that, there was already evidence for what came to be known as “Prozac poopout”: the drug often stopped working after a few weeks or months. Such worrying signs increased over the next two decades, becoming a steady cascade of possible side effects and withdrawal symptoms that ranged from the prosaic (headaches, rashes, insomnia, digestive problems, joint pain) to the more disturbing (dyskinesia, rigid or trembling limbs, loss of fine motor control, sexual side effects amounting to a virtual shutdown of erotic life) to the frankly dire (abnormal bleeding and the potential for stroke in older people, and self-harm and suicidal thinking in children and adolescents).

Even worse, during the ’90s and the first decade of the 21st century, a small flood of psychiatric papers and research studies argued that antidepressants didn’t work well in the first place. After a few weeks of improvement, depressed patients often returned to the status quo ante and had to have their dosage increased or supplemented with other drugs. When antidepressants did work, the results were often—particularly for milder and moderate forms of depression—little if any better than placebo. And what was described as a relapse in people who stopped taking the drugs—redoubled depression, anxiety, insomnia—might really be withdrawal symptoms. There was even evidence for the depressogenic effects of the drugs, which acted on brain chemistry all right, but in the wrong way, making some people even more depressed and turning what might have been a temporary depressive episode into a chronic condition.

One reason we know about these developments at all is because a dedicated little army of muckraking mental health experts has produced a steady stream of books, articles, blogs, and websites devoted to publicizing what they regard as the money-driven, ethically challenged “drug culture” perpetrated by Big Pharma in collusion with the much-compromised field of psychiatry. Books like The Emperor’s New Drugs: Exploding the Antidepressant Myth (2009) by Irving Kirsch, Let Them Eat Prozac: The Unhealthy Relationship Between the Pharmaceutical Companies and Depression (2004) by David Healy, Comfortably Numb: How Psychiatry is Medicating a Nation (2008) by Charles Barber, and Anatomy of an Epidemic: Psychiatric Drugs and the Astonishing Rise of Mental Illness in America (2011) by Robert Whitaker not only excoriate the societywide overuse of antidepressant and other psychotropic medications, but relentlessly dig up dirt about the research that presumably justified the drugs in the first place.

Besides the well-known charge that drug companies routinely publish more than twice as many of their positive findings as negative ones (hiding the trials that proved unfavorable to the drug), these detectives revealed they also produce meta-analyses that are themselves drawn from pools of successful trials (ignoring the unsuccessful ones). Drug companies, it turns out, ghost-write studies (designing and conducting them, then analyzing the data) and publish them under the names of prominent physicians, who are often paid consultants for the companies. Overall, because there’s so much dough riding on encouraging outcomes, drug companies—and even the National Institute of Mental Health—stand accused of routinely inflating positive findings, omitting or hiding relevant negative data, and gaming the numbers in ways that make the results look fishy, to say the least.

Thus, the evidence for the routine use of antidepressants has increasingly come to be seen as pretty feeble. Generally, antidepressants seem to work well for seriously depressed people, but not so much for the vaster, far less emotionally disabled population for whom they’re usually prescribed. Even in drug company trials, placebos relieved mild or moderate depression as well as antidepressants. In other words, for the kind of ordinary, scratchy unhappiness that Freud found characteristic of human existence (at least among the Viennese bourgeoisie) and that primary-care doctors see all the time in modern America, antidepressants were not measurably helpful.

Perhaps a major problem lies in the possibility that nobody really knows what depression is. As Edward Shorter puts it in his latest book, How Everyone Became Depressed, “The current DSM classification is a jumble of nondisease entities, created by political fighting within psychiatry, by competitive struggles in the pharmaceutical industry, and by the whimsy of regulators.” The result is the metastasizing growth of conditions for which antidepressants are considered the remedy. Depression is today such a malleable, shape-shifting term for such a mass of mental and physical symptoms that no single class of drug could be expected to resolve them all. Is depression a debilitating hopelessness, sense of guilt, loss of all ability to feel pleasure, or even to feel anything at all. Is it also a somewhat lesser state of misery, which might include anxiety, irritability, fatigue, disappointment, and discouragement, with maybe some somatic symptoms (insomnia, digestive problems) thrown in? Hmmm. Is it the reactive misery and fear following the loss of a job, a spouse, a house to foreclosure? Or is depression the hidden lever behind a chronic sense of insecurity and low self-esteem, loneliness, and social awkwardness? Who knows? Since both the formal and informal definition of depression has become so murky, inclusive—boundless, even—any combination of these, any subjective experience of unhappiness, can qualify.

At this point, you might wonder what difference it makes since—right or wrong, good or bad—antidepressants rule. We might just as well get used to it and take our meds, right? But, in fact, the whole antidepressant empire shows signs of being seriously in trouble. Sales are down from their high-water mark of $13 billion in 2008 to $9.4 billion in 2013—and still slipping about 4 percent a year. The reason isn’t because people are taking fewer of them, but because so many patents are expiring, leaving, at the moment, 40 percent of the market to generics—a percentage that will increase over the next two years. At this point, the great promises of neuroscience for new and better pharmaceutical treatments haven’t been fulfilled, not remotely. It’s been nearly 40 years since the discovery of lithium, antipsychotics, and antidepressants, but that serendipitous wave of discovery was followed by what can most charitably be described as a lull, and any understanding of the neurobiology underlying psychopathology remains severely limited. For the first time, the fabled pharmaceutical antidepressant pipeline, from which ever more ingenious combinations of molecules have gushed forth, seems to have run dry.

—–

So are there any lessons to be drawn from this 150-year boom/bust cycle of American psychopharm? One would seem to be that most of these drugs (even heroin, on occasion, and the once-popular cannabis, now making its comeback tour) often did and still do—in the right conditions, with the right people—bring almost miraculous relief from intractable pain and suffering, physical and mental. Many psychoactive drugs loved not wisely but too well actually did “work”—in their own way, they could be considered as miraculous as antibiotics. Today, millions of people who’ve taken antidepressants feel they’ve been helped; many are convinced that the drugs have literally saved their lives. But like antibiotics, the drugs could be victims of their own success, done in by runaway marketing, excessive enthusiasm, and flagrant overuse.

At this point, to vilify antidepressants after having idolized them for so long suggests an old American temptation to think in black-and-white terms, veering from infatuation with a pharmaceutical quick fix to furious outrage when the fix doesn’t immediately fix everything. So far, antidepressants have escaped the moral outrage and panic of earlier drugs because they don’t carry even a whiff of the threat associated with cocaine or methamphetamine. It’s hard to imagine antidepressants having much appeal as illegal street drugs, given that it takes weeks for them to have any psychotropic effect. Although their cultural stock, not to say their financial stock, has declined, it’s a little early to say they’re through. As biological psychologist Peter Etchells put it in an August 2013 Guardian article, none of the controversy “means that antidepressants don’t work. It just means that we don’t know yet.” Etchells went on to say more research was needed “that isn’t influenced by monetary gains or emotional predispositions toward one outcome or another.” To which one may be tempted to respond, “Good luck with that.” From what planet are these judicious, not-influenced-by-money-or-emotion types supposed to come?

In the meantime, we can anticipate the excesses likely to come with the legalization and spread of marijuana. Today, in Colorado, you can already buy marijuana elixirs (sparkling peach, red currant, blueberry, pomegranate), foods (chocolates, cheesecakes, hard candies, candy bars, sodas), botanical drops (cinnamon, ginger-mango, vanilla, watermelon), capsules, balms, pills, and old-fashioned smokables, including hash, in different flavors no hophead of yesteryear could imagine: Lemon Skunk, True Purple, Mother’s Poison, and Black Bubba, to name just a few. Financial stocks in weed production and marketing have shot up in Colorado and Washington (where pot is also legal), and there is now a growth industry, not only in pot sales, but in books and financial services to people who want to invest in the cannabis sector of the economy. Are we on the verge of another best-drug-ever bubble? Is America a capitalist country? Do Americans like mind-altering drugs?

How will the next psychotropic miracle fare? Tune in here a decade from now for the follow-up story.

Resources

Hicks, Jesse. “Fast Times: The Life, Death, and Rebirth of Amphetamine.” Chemical Heritage Magazine, Spring 2012.

Kandall, Stephen. Substance and Shadow: Women and Addiction in the United States. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1996.

López-Muñoz, Francisco, et al. “The History of Barbiturates a Century after Their Clinical Introduction.” Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment 1, no. 4 (December 2005): 329–343.

Rasmussen, Nicolas. On Speed: The Many Lives of Amphetamine, NYU Press, 2009.

Rasmussen, Nicolas. “America’s First Amphetamine Epidemic 1929–1971, American Journal of Public Health 98, no. 6 (June 2007).

Shorter, Edward. Before Prozac: The Troubled History of Mood Disorders in Psychiatry, Oxford University Press, 2008.

Tone, Andrea. The Age of Anxiety: A History of America’s Turbulent Affair with Tranquilizers, Basic Books, 2008.

Photo © Corbis Images

Mary Sykes Wylie

Mary Sykes Wylie, PhD, is a former senior editor of the Psychotherapy Networker.