Enjoy the audio preview version of this article—perfect for listening on the go.

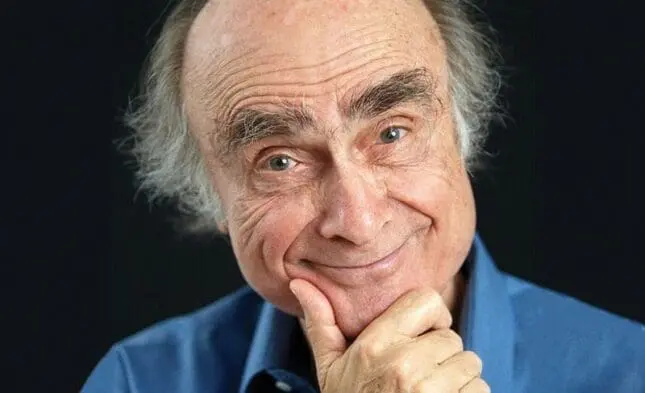

PSYCHOTHERAPY NETWORKER: You’re 95 now and have been retired from practice for 20 years, so you have an unusually broad perspective on how therapists experience the different stages of their life and career. What aspects of your own aging process have had the biggest impact on your approach to psychotherapy?

POLSTER: It was a gradual process, and I’m sure there were many changes over the years. Maybe the one I noticed the most was how I grew more at home with what I was doing. I didn’t have to think as deliberately about the relationships I had with clients, and I didn’t have to work so hard. It was like being at home.

I no longer felt I had to be this way or that way to conform to some theoretical system. I didn’t have to think about the empty chair or about making up statements beginning with the word you. I was much more oriented toward the flow of the relationship between me and whomever I was working with.

PN: Was there anything that became harder or more challenging?

POLSTER: Even when I wanted to keep up with the new developments in the field, I found it harder to get involved with the latest innovations, like EMDR. I heard about them, but I wasn’t as motivated to explore them as I would’ve been 30 years earlier.

PN: Are there some experiences you’ve had, whether in your practice or in your life, that have had a particular impact on your attitude about facing mortality?

POLSTER: For most of us, facing mortality is pretty much a gradual process. But the first serious confrontation I had with it was when my wife, Miriam, was dying. In some ways, I experienced her death as a threat to my existence. We’d been married 52 years, and I just didn’t know how my life would proceed without her. When she died, I had this strange sense of incoherence about my being alive while she was dead. It was something of an introspective challenge to put those two things together. I never thought that I don’t want to go on if I can’t be with her, but I certainly had an accentuated sense of not taking things for granted in life.

PN: Was there something about all those years of being a therapist that had a big impact on how you handled the challenge of losing her?

POLSTER: Since I was never not a psychotherapist, at least not as an adult, it’s a little hard to say, but one of the things that shaped how I went through that experience was the therapist’s instinct to fit what’s happening into a context.

Psychotherapy is a very special experience, and one behaves in psychotherapy from an introspective standpoint that one may not have in everyday life when things simply follow each other in the flow of time. So largely, life just flowed with all its happenings. But I was never unaware that I was heading toward a different stage of my life, and I didn’t know what it would be like.

I must say, however, I never felt a lot of difference in my basic internal energy. The same energy that I had when I was five years old, I still had when I was 85 years old. I still have it now, even as I speak to you, at this very moment, at 95. That kind of vital energy has nothing much to do with the fact that I know I don’t have much longer to go.

Engagement in the moment is the key factor for me. Being engaged in this conversation with you, for example, I could be 17 or 67—it wouldn’t make any difference. I’m not feeling fundamentally different in terms of excitement, or involvement, or absorption than I might have felt at any age. But when I’m not engaged, then my mind is very different.

PN: What’s the biggest difference between your being in or out of the experience of engagement?

POLSTER: You might say that as I’ve gotten older, I don’t have the same kind of—what shall I call it?—fluidity of opportunity. As a younger person, things would evolve more fluidly from moment to moment. There was a sense that there was always something going on. Often those experiences were arousing, and illuminating, and inspirational. These days I don’t have those options in the same way. I can’t decide to go out and just pick up batteries for my radio. I can’t drive, so somebody has to do it with me or for me. It’s a whole different ballgame.

PN: Is there anything about all your experiences as a therapist that stands out as providing especially important learnings?

POLSTER: The main thing I learned from being a therapist is that it’s really good to love what you’re doing. And for the many years I practiced as a therapist, I loved what I was doing. But to me, there’s nothing inherent about being a therapist that would be different from being, let’s say, an actor or an electrician, or any of the many things one could be. The important thing is that you love doing it. When I was younger, I thought I’d much rather be a major league ballplayer, but I’ve changed my mind, and I think I did the right thing.

PN: What was it about being a therapist that you loved so much?

POLSTER: I loved being engaged. I loved mattering. I loved digging deeper into the specifics of the moment. I liked the sense of being myself and also feeling like a member of the wider human community.

PN: It’s been 20 years since you’ve practiced. What’s it like to have given up something that you loved so much for so long?

POLSTER: I miss the action, but I never wake up in the morning wishing I could do a little psychotherapy today. When I retired and it became clear that I wasn’t going to take on any new clients, I could hardly wait to end my practice.

PN: That’s a bit surprising to hear. What do you think that was about?

POLSTER: I don’t know, but I think it was just a matter of the commitment. For me, there was something appealing about being free of the commitment that comes with being a therapist. Although I loved doing the therapy, at some point I didn’t like that I had to do it every day.

I had no freedom to respond to some personal need on a particular day. One day I even had the thought, I’m going to tell everybody that if they’re in therapy with me for as much as a year, there’ll be three times that they’ll come in and I won’t be here. Of course, I never said it, knowing how painful it could be for some clients, but I did have that fantasy about giving myself some freedom in that sense. So when you’re talking about what happened at the end of my career, it wasn’t that I was no longer enjoying doing therapy. I just didn’t want the commitment.

PN: At this point in your life, do you find that the way you think about death has changed?

POLSTER: The concept of ending is a difficult one to think about. I don’t believe in the afterlife. So when I die, I imagine it’s going to be like someone has turned out the lights. Basically, it’s a strange paradox. Of course, I care what other people will feel, but I won’t be around to have a part in it one way or another. Things matter only because they matter, not for any larger reason other than that it’s in our nature for things to matter. So when I die, after I die, it’s not going to matter. But before I die, it matters.

I’m aware that I’m very close to death and that it could happen any time. But I’m not especially distracted by it, except when I’m not engaged in my day-to-day life. Then it occurs to me more, and sometimes I feel some fear about it. But most of the time I feel nothing much about death. It’s like it’s just a thought. Maybe the most important thing I’ve learned about growing old is that when you’re old, you’re old, but you’re still alive, and well, life is life.