Over the last few months, as we began to work on this issue on kids and families in therapy, magazines around the country began to invade our territory, suddenly turning childrearing into the topic du jour. In rapid succession, elite magazines like the Atlantic, The New Republic, and even The Economist, as if simultaneously picking up on the mysterious emanations of an emerging cultural trend, devoted lengthy features to a growing suspicion that something isn’t right with the way we’re raising our children today. It’s not that they’re neglected and abused—although, unfortunately, at times this is the case—but something like just the reverse: they’re so overprotected, overprogrammed, overeducated, and overcontrolled that they seem unable to genuinely grow up and achieve full psychological personhood.

As polished and thoroughly researched as these other magazine pieces have been, from our perspective, they seemed to beg the fundamental therapeutic questions they raised. For one thing, they ignore the heart of the matter: has the time come to consider whether the profound changes in our economy, technology, and culture over these last couple of decades have opened up a breach in the very experience of intimate connection in middle-class families around the world? And if so, what can we as therapists do about it?

For a boomer like myself, it’s hard to escape the conclusion that the fundamental rules of adequate childrearing have been radically transfigured since the dinosaur years of my own childhood. For those of us who grew up in the 1950s and early ’60s, there was a kind of assurance in the very air we breathed that, as members in good standing of the great American middle class, our future was safe— we’d probably never be rich or famous, but we knew that one day we’d grow up, graduate from high school, go to college, get a job, marry, produce kids, and probably raise them pretty much the way we were raised. But today, that assurance, that sense of inner security that used to be considered the birthright of American families, has vanished. In its place is a rankling anxiety, a sense in parents and their kids that childrearing takes place in a kind of war zone, in which danger lurks everywhere and the future is a dark, uncertain void.

In this issue, the contributors invite us to stand back from the day-to-day rush of our professional lives and connect dots we may not have linked up on our own. From their experiences in the consulting room, they consider whether there’s there an emerging norm under which parents don’t emotionally directly engage their children as much as they regard them as demanding, long-range parenting projects. In his cover piece, Ron Taffel observes a trend in the families he sees toward turning the responsibilities of parenting into a self-conscious competition to create and develop the most marketable child-as-product that money and time can manufacture. He wonders whether the jangling rhythms and constant distractions of daily life, combined with unrelenting pressures to succeed, are fraying the bonds of attachment that undergird family life and child development.

Some may argue that the human race is dealing with worse threats to children (do I need to mention Gaza, Syria, Honduras, or any other of a dozen current hellholes?) than overzealous parents agonizing over their kids’ chances at getting into Harvard. But if this issue’s contributors are correct, we’re just beginning to recognize a crisis of connection with our children that both our society and our profession can no longer ignore.

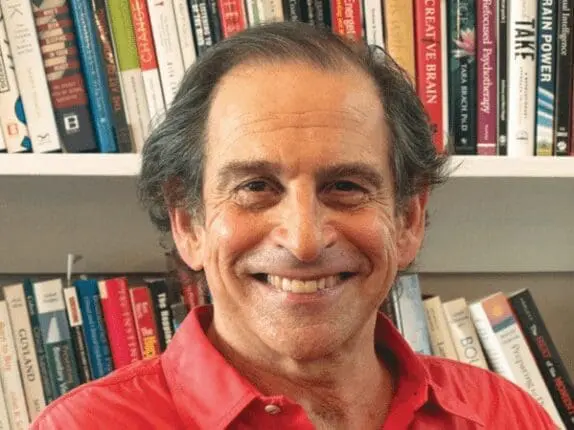

Rich Simon

Richard Simon, PhD, founded Psychotherapy Networker and served as the editor for more than 40 years. He received every major magazine industry honor, including the National Magazine Award. Rich passed away November 2020, and we honor his memory and contributions to the field every day.